ART ON VIEW

96

oil with hot peppers, condiments, and relish to their

husbands in these bowls. Royal wives would compete

to have the fi nest bowls and typically displayed them

prominently in their homes.13 Even today, female potters

continue to make such bowls for women to use.

Historically, terracotta and wooden serving bowls

(fi g. 8) started as dual-purpose objects, to be used

for food and as lamps. They were typically footless

with a handle and spout for the wick to rest on. Over

time, the spout became a decorative element without

a functional purpose,14 and intricate openwork

stands became common.15 The intricacy of the carving

in these earlier examples varied, and, as is the

case with other dining paraphernalia, the prestige

conveyed by the fi neness of production is enhanced

by the inclusion of royal or other restricted iconography.

Bowls with handles depicting human heads are

linked only to palace use, while bowls with spider

or frog motifs could be found in the palace or in the

homes of lineage heads.

Hospitality in the palace also involves sharing kola

nuts, which when chewed are a mild stimulant and

have long been a fi xture of daily life in the Grassfi

elds. Historically, men ate the pink-and-white nuts

throughout the day, rarely leaving home without

them. In the palace, the king always had a supply

of kola nuts to give to men and honored women on

ceremonial occasions. Ornately carved bowls lined

with fresh leaves were important to their presentation.

They, too, had royal iconography, highlighting

the fact that the king shares his kola nuts in a gesture

of hospitality and show of trust.16

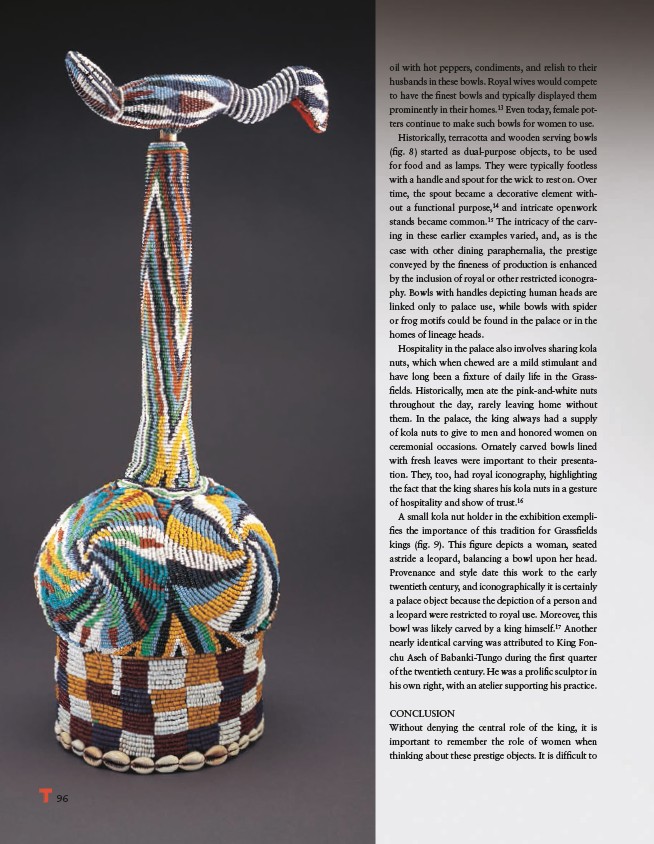

A small kola nut holder in the exhibition exemplifi

es the importance of this tradition for Grassfi elds

kings (fi g. 9). This fi gure depicts a woman, seated

astride a leopard, balancing a bowl upon her head.

Provenance and style date this work to the early

twentieth century, and iconographically it is certainly

a palace object because the depiction of a person and

a leopard were restricted to royal use. Moreover, this

bowl was likely carved by a king himself.17 Another

nearly identical carving was attributed to King Fonchu

Aseh of Babanki-Tungo during the fi rst quarter

of the twentieth century. He was a prolifi c sculptor in

his own right, with an atelier supporting his practice.

CONCLUSION

Without denying the central role of the king, it is

important to remember the role of women when

thinking about these prestige objects. It is diffi cult to