Dining with Kings

Ceremony and Hospitality in

the Cameroon Grassfields

By Erica P. Jones

91

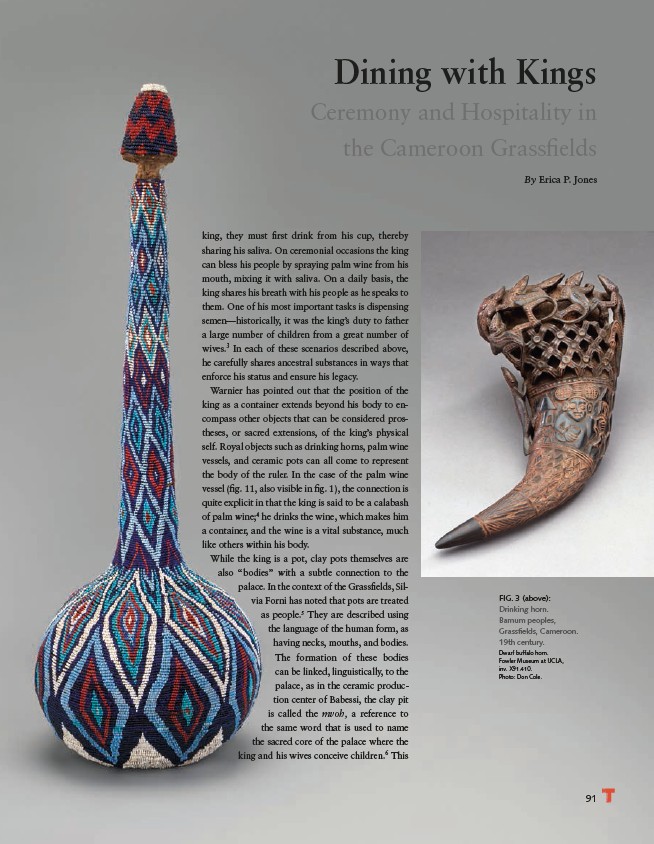

FIG. 3 (above):

Drinking horn.

Bamum peoples,

Grassfields, Cameroon.

19th century.

Dwarf buffalo horn.

Fowler Museum at UCLA,

inv. X91.410.

Photo: Don Cole.

king, they must first drink from his cup, thereby

sharing his saliva. On ceremonial occasions the king

can bless his people by spraying palm wine from his

mouth, mixing it with saliva. On a daily basis, the

king shares his breath with his people as he speaks to

them. One of his most important tasks is dispensing

semen —historically, it was the king’s duty to father

a large number of children from a great number of

wives.3 In each of these scenarios described above,

he carefully shares ancestral substances in ways that

enforce his status and ensure his legacy.

Warnier has pointed out that the position of the

king as a container extends beyond his body to encompass

other objects that can be considered prostheses,

or sacred extensions, of the king’s physical

self. Royal objects such as drinking horns, palm wine

vessels, and ceramic pots can all come to represent

the body of the ruler. In the case of the palm wine

vessel (fig. 11, also visible in fig. 1), the connection is

quite explicit in that the king is said to be a calabash

of palm wine;4 he drinks the wine, which makes him

a container, and the wine is a vital substance, much

like others within his body.

While the king is a pot, clay pots themselves are

also “bodies” with a subtle connection to the

palace. In the context of the Grassfields, Silvia

Forni has noted that pots are treated

as people.5 They are described using

the language of the human form, as

having necks, mouths, and bodies.

The formation of these bodies

can be linked, linguistically, to the

palace, as in the ceramic production

center of Babessi, the clay pit

is called the mvoh, a reference to

the same word that is used to name

the sacred core of the palace where the

king and his wives conceive children.6 This