ART ON VIEW

are embroidered with traditional Bamum royal symbols.

94

Photographs from the early twentieth century

show the king with missionaries sitting around a table

covered by a Bamum-produced tablecloth (fi g.

7). While there is no indication that he used these

locally produced tablecloths in daily palace life, it is

clear that King Njoya saw the value of using them

with European visitors (fi g. 7). The tablecloth in the

Fowler’s collection has a rosette at the center surrounded

by Bamum iconographic motifs, notably

the serpent, buffalo, lizard, and bird. Origin stories

claim that the kingdom’s founders determined

its current location by following a serpent, linking

the lineage of royal ancestors with the reptile. The

buffalo is associated with power throughout the

Grasslands region because of its size and strength.

While not exclusively used by royal artists, it is commonly

deployed to symbolize the loyalty of people

who serve the palace. Along the tablecloth’s border

is a highly stylized version of the repeating frog motif,

widely used to represent fertility. By melding this

European form with Bamum iconographic elements,

this gift encapsulated King Njoya’s diplomatic savvy;

he managed to give his guest something that was

both familiar and foreign.

ROYAL IMBIBING

The king is the focal point of many ceremonial settings

in the Cameroon Grassfi elds. He is a fi gure

surrounded by, and covered in, objects that convey

power and prestige. His clothing sets him apart as

the most fi nely dressed man in attendance, and he

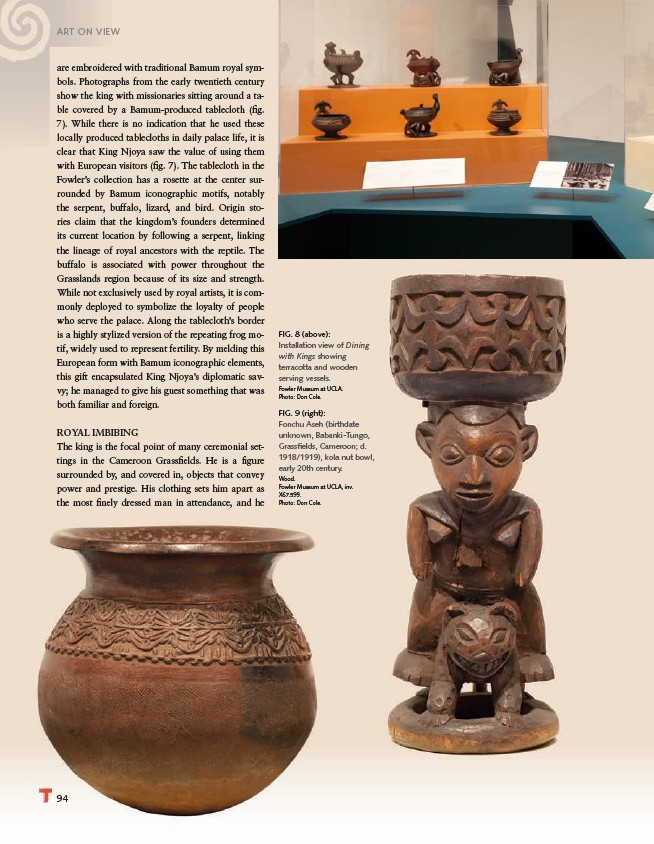

FIG. 8 (above):

Installation view of Dining

with Kings showing

terracotta and wooden

serving vessels.

Fowler Museum at UCLA.

Photo: Don Cole.

FIG. 9 (right):

Fonchu Aseh (birthdate

unknown, Babanki-Tungo,

Grassfi elds, Cameroon; d.

1918/1919), kola nut bowl,

early 20th century.

Wood.

Fowler Museum at UCLA, inv.

X67.599.

Photo: Don Cole.