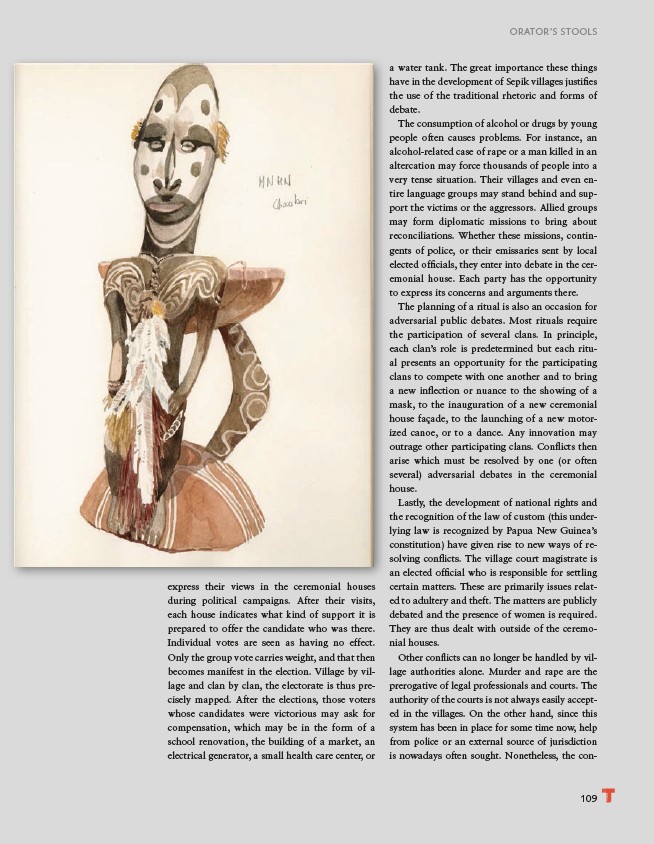

ORATOR’S STOOLS

109

express their views in the ceremonial houses

during political campaigns. After their visits,

each house indicates what kind of support it is

prepared to offer the candidate who was there.

Individual votes are seen as having no effect.

Only the group vote carries weight, and that then

becomes manifest in the election. Village by village

and clan by clan, the electorate is thus precisely

mapped. After the elections, those voters

whose candidates were victorious may ask for

compensation, which may be in the form of a

school renovation, the building of a market, an

electrical generator, a small health care center, or

a water tank. The great importance these things

have in the development of Sepik villages justifi es

the use of the traditional rhetoric and forms of

debate.

The consumption of alcohol or drugs by young

people often causes problems. For instance, an

alcohol-related case of rape or a man killed in an

altercation may force thousands of people into a

very tense situation. Their villages and even entire

language groups may stand behind and support

the victims or the aggressors. Allied groups

may form diplomatic missions to bring about

reconciliations. Whether these missions, contingents

of police, or their emissaries sent by local

elected offi cials, they enter into debate in the ceremonial

house. Each party has the opportunity

to express its concerns and arguments there.

The planning of a ritual is also an occasion for

adversarial public debates. Most rituals require

the participation of several clans. In principle,

each clan’s role is predetermined but each ritual

presents an opportunity for the participating

clans to compete with one another and to bring

a new infl ection or nuance to the showing of a

mask, to the inauguration of a new ceremonial

house façade, to the launching of a new motorized

canoe, or to a dance. Any innovation may

outrage other participating clans. Confl icts then

arise which must be resolved by one (or often

several) adversarial debates in the ceremonial

house.

Lastly, the development of national rights and

the recognition of the law of custom (this underlying

law is recognized by Papua New Guinea’s

constitution) have given rise to new ways of resolving

confl icts. The village court magistrate is

an elected offi cial who is responsible for settling

certain matters. These are primarily issues related

to adultery and theft. The matters are publicly

debated and the presence of women is required.

They are thus dealt with outside of the ceremonial

houses.

Other confl icts can no longer be handled by village

authorities alone. Murder and rape are the

prerogative of legal professionals and courts. The

authority of the courts is not always easily accepted

in the villages. On the other hand, since this

system has been in place for some time now, help

from police or an external source of jurisdiction

is nowadays often sought. Nonetheless, the con-