and father of all living things, the connection between man and

nature, and the guardian of the country’s laws. The fi nal part of

the exhibition is devoted to the work of the Ghost Net weavers

(fi g. 8) and explores environmental preservation. It goes without

saying that this is a global issue that has great relevance for

twenty-fi rst-century Western societies.

It’s unusual that there would be three exhibitions devoted to

Aboriginal art happening at the same time in Switzerland—

one at the MEG, a second at the university, and the one we’re

discussing, the Pierre Arnaud Foundation. Is this the result of a

particular infatuation with this art in this country?

The concurrence of these three events owes much to chance

and has no particular signifi cance in and of itself. Nonetheless,

Switzerland has been a pioneer in the appreciation of this

art in some respects. This is referenced in the exhibition and

extensively discussed in the accompanying book. For example,

just over 100 years ago, in December of 1917, Tristan Tzara

recited his Chanson du serpent (Serpent’s Song) at the now

famous Cabaret Voltaire, thus introducing Australian Aboriginal

culture to the world of contemporary Western art. This song,

which the Dada artist found in the seven-volume work by Carl

Strehlow on the Arrernte and Luritja of Central Australia, refers

to one of the most important ways in which the stories that

nourish and inspire Australian art, even in its most contemporary

manifestations, such as the acrylic-on-canvas paintings

that began to appear in the 1970s, were and continue to be

transmitted.

143

Three Questions for Exhibition Curator

Georges Petitjean

How would you characterize Bérengère

Primat’s collection?

In my opinion as an art historian, it’s

the most important and engaged private

collection in Europe, and although it was

built from the heart, it has astonishing

coherence and comprehensiveness that

I believe it gets from being built on

some very sound anchor points. I would

note Arnhem Land specifi cally, and

the work of artist John Mawurndjul,

whose paintings were seen in the notable

Magiciens de la Terre exhibition at

the Centre Pompidou in 1989. He

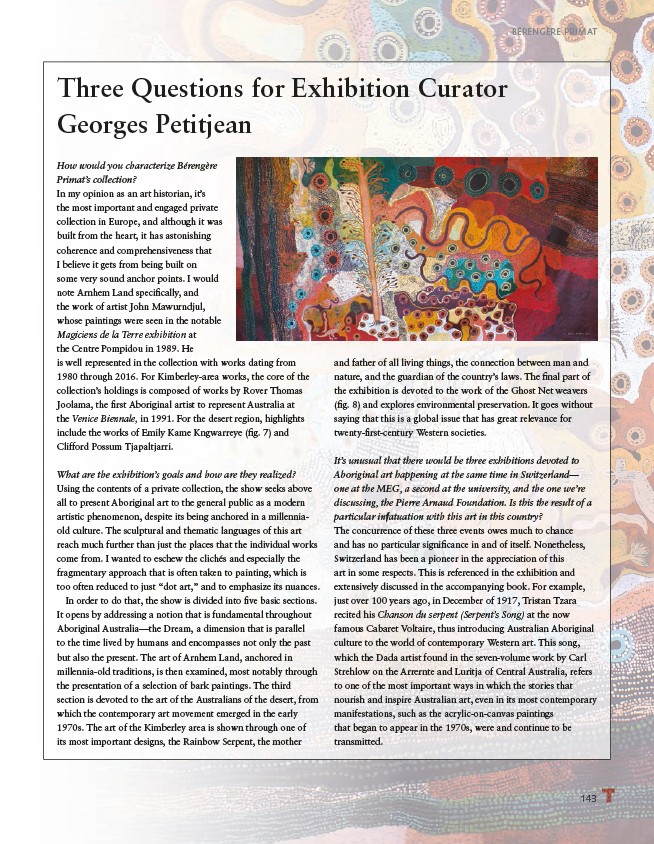

is well represented in the collection with works dating from

1980 through 2016. For Kimberley-area works, the core of the

collection’s holdings is composed of works by Rover Thomas

Joolama, the fi rst Aboriginal artist to represent Australia at

the Venice Biennale, in 1991. For the desert region, highlights

include the works of Emily Kame Kngwarreye (fi g. 7) and

Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri.

What are the exhibition’s goals and how are they realized?

Using the contents of a private collection, the show seeks above

all to present Aboriginal art to the general public as a modern

artistic phenomenon, despite its being anchored in a millenniaold

culture. The sculptural and thematic languages of this art

reach much further than just the places that the individual works

come from. I wanted to eschew the clichés and especially the

fragmentary approach that is often taken to painting, which is

too often reduced to just “dot art,” and to emphasize its nuances.

In order to do that, the show is divided into fi ve basic sections.

It opens by addressing a notion that is fundamental throughout

Aboriginal Australia—the Dream, a dimension that is parallel

to the time lived by humans and encompasses not only the past

but also the present. The art of Arnhem Land, anchored in

millennia-old traditions, is then examined, most notably through

the presentation of a selection of bark paintings. The third

section is devoted to the art of the Australians of the desert, from

which the contemporary art movement emerged in the early

1970s. The art of the Kimberley area is shown through one of

its most important designs, the Rainbow Serpent, the mother

BÉRENGÈRE PRIMAT