83

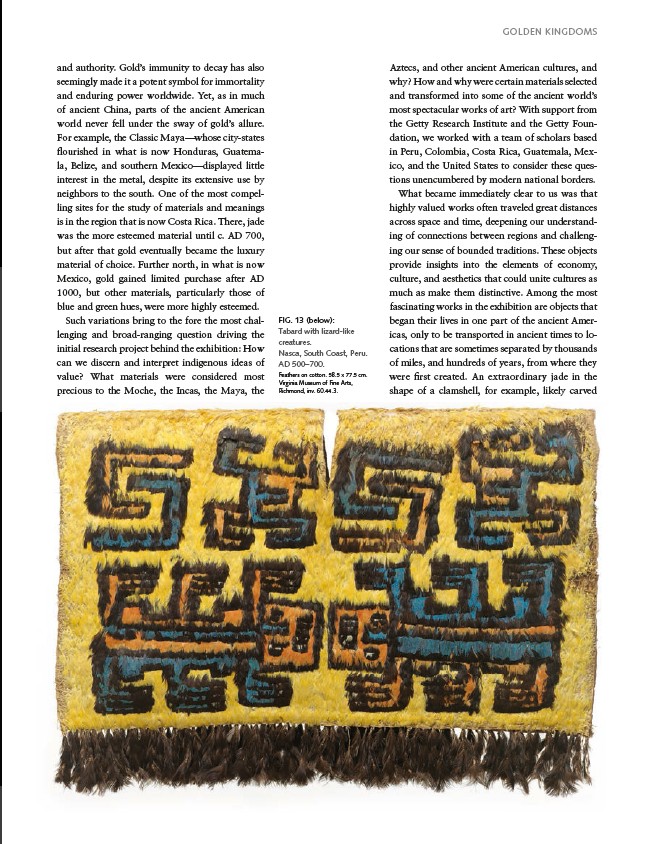

FIG. 13 (below):

Tabard with lizard-like

creatures.

Nasca, South Coast, Peru.

AD 500–700.

Feathers on cotton. 58.5 x 77.5 cm.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts,

Richmond, inv. 60.44.3.

GOLDEN KINGDOMS

and authority. Gold’s immunity to decay has also

seemingly made it a potent symbol for immortality

and enduring power worldwide. Yet, as in much

of ancient China, parts of the ancient American

world never fell under the sway of gold’s allure.

For example, the Classic Maya—whose city-states

flourished in what is now Honduras, Guatemala,

Belize, and southern Mexico—displayed little

interest in the metal, despite its extensive use by

neighbors to the south. One of the most compelling

sites for the study of materials and meanings

is in the region that is now Costa Rica. There, jade

was the more esteemed material until c. AD 700,

but after that gold eventually became the luxury

material of choice. Further north, in what is now

Mexico, gold gained limited purchase after AD

1000, but other materials, particularly those of

blue and green hues, were more highly esteemed.

Such variations bring to the fore the most challenging

and broad-ranging question driving the

initial research project behind the exhibition: How

can we discern and interpret indigenous ideas of

value? What materials were considered most

precious to the Moche, the Incas, the Maya, the

Aztecs, and other ancient American cultures, and

why? How and why were certain materials selected

and transformed into some of the ancient world’s

most spectacular works of art? With support from

the Getty Research Institute and the Getty Foundation,

we worked with a team of scholars based

in Peru, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico,

and the United States to consider these questions

unencumbered by modern national borders.

What became immediately clear to us was that

highly valued works often traveled great distances

across space and time, deepening our understanding

of connections between regions and challenging

our sense of bounded traditions. These objects

provide insights into the elements of economy,

culture, and aesthetics that could unite cultures as

much as make them distinctive. Among the most

fascinating works in the exhibition are objects that

began their lives in one part of the ancient Americas,

only to be transported in ancient times to locations

that are sometimes separated by thousands

of miles, and hundreds of years, from where they

were first created. An extraordinary jade in the

shape of a clamshell, for example, likely carved