FEATURE

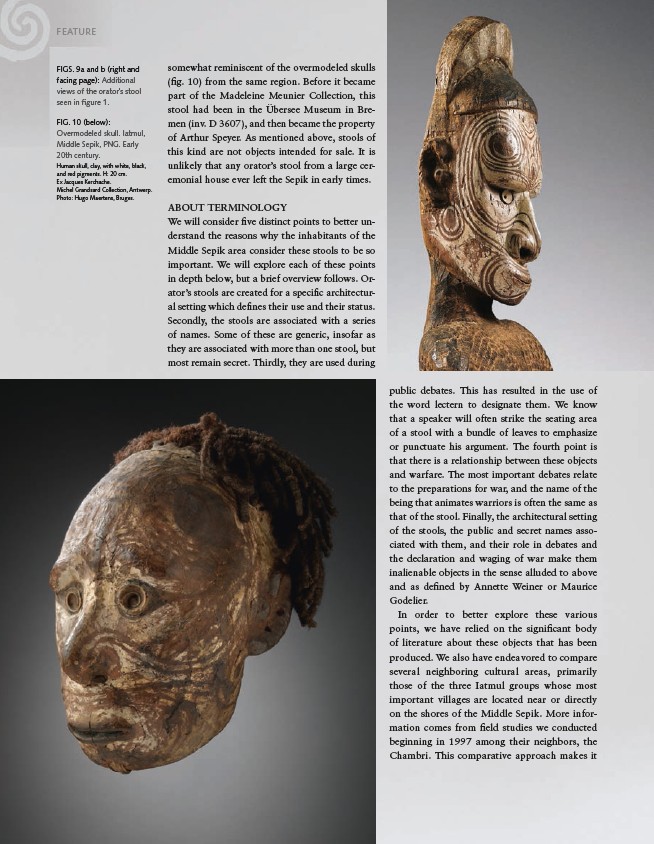

FIGS. 9a and b (right and

facing page): Additional

views of the orator’s stool

seen in fi gure 1.

FIG. 10 (below):

Overmodeled skull. Iatmul,

Middle Sepik, PNG. Early

20th century.

Human skull, clay, with white, black,

and red pigments. H: 20 cm.

Ex Jacques Kerchache.

Michel Grandsard Collection, Antwerp.

Photo: Hugo Maertens, Bruges.

102

somewhat reminiscent of the overmodeled skulls

(fi g. 10) from the same region. Before it became

part of the Madeleine Meunier Collection, this

stool had been in the Übersee Museum in Bremen

(inv. D 3607), and then became the property

of Arthur Speyer. As mentioned above, stools of

this kind are not objects intended for sale. It is

unlikely that any orator’s stool from a large ceremonial

house ever left the Sepik in early times.

ABOUT TERMINOLOGY

We will consider fi ve distinct points to better understand

the reasons why the inhabitants of the

Middle Sepik area consider these stools to be so

important. We will explore each of these points

in depth below, but a brief overview follows. Orator’s

stools are created for a specifi c architectural

setting which defi nes their use and their status.

Secondly, the stools are associated with a series

of names. Some of these are generic, insofar as

they are associated with more than one stool, but

most remain secret. Thirdly, they are used during

public debates. This has resulted in the use of

the word lectern to designate them. We know

that a speaker will often strike the seating area

of a stool with a bundle of leaves to emphasize

or punctuate his argument. The fourth point is

that there is a relationship between these objects

and warfare. The most important debates relate

to the preparations for war, and the name of the

being that animates warriors is often the same as

that of the stool. Finally, the architectural setting

of the stools, the public and secret names associated

with them, and their role in debates and

the declaration and waging of war make them

inalienable objects in the sense alluded to above

and as defi ned by Annette Weiner or Maurice

Godelier.

In order to better explore these various

points, we have relied on the signifi cant body

of literature about these objects that has been

produced. We also have endeavored to compare

several neighboring cultural areas, primarily

those of the three Iatmul groups whose most

important villages are located near or directly

on the shores of the Middle Sepik. More information

comes from fi eld studies we conducted

beginning in 1997 among their neighbors, the

Chambri. This comparative approach makes it