FEATURE

108

they are in the ceremonial houses of Palimbei

(Payembit), Kanganamun, and Yentchen.22

3. DEBATE

The function ordinarily attributed to orator’s

stools is associated with taking the fl oor in public

speaking. We owe most of what we know about

the Iatmul oratorical arts to Gregory Bateson23

and to Milan Stanek.24 The men’s house is something

like a club. A man enters and stays for as

long as he wishes. The rules are usually quite

loose, and while it is preferred that one sit on

the benches of one’s own clan or moiety, a seat

can also be taken near one or more people with

whom he wishes to converse.

On certain occasions, a ranking man in the

clan can take the initiative of calling for a meeting.

A specifi c rhythm that calls one or several

clans is then played on the slit drum to summon

the appropriate men. In some circumstances, the

rules are followed more closely and then each

man takes a seat on his clan’s bench that is determined

by his rank, or age. The older one is,

the closer to the center of the bench one sits.

The younger ones are closer to the bench’s ends.

When a gathering requires discussion to achieve

consensus, the taking of the fl oor is ritualized.

In this situation, only the mature men (between

about thirty-fi ve and forty-fi ve years of age) may

speak. Older men generally abstain. However,

it is often said that the younger men who speak

are under their infl uence and even that they are

simply repeating what their elders have directed

them to say.

These days, the subjects that are debated in

the ceremonial houses primarily relate to property

rights. The ownership and use of land and

the waterways and paths near the Sepik, are,

as they are elsewhere, important subjects. Disagreements

may lead to physical confrontations,

sometimes even armed ones. Questions related

to environmental issues—drought, excessive

rain, or, as Gewertz notes, suspicious illnesses

(1977: 347 and following pages)—also call for

debate. These may be held in smaller or larger

ceremonial houses, depending on the importance

of the problems being discussed and the number

of people they concern.

National and local elections are also among

the subjects debated. Candidates are invited to

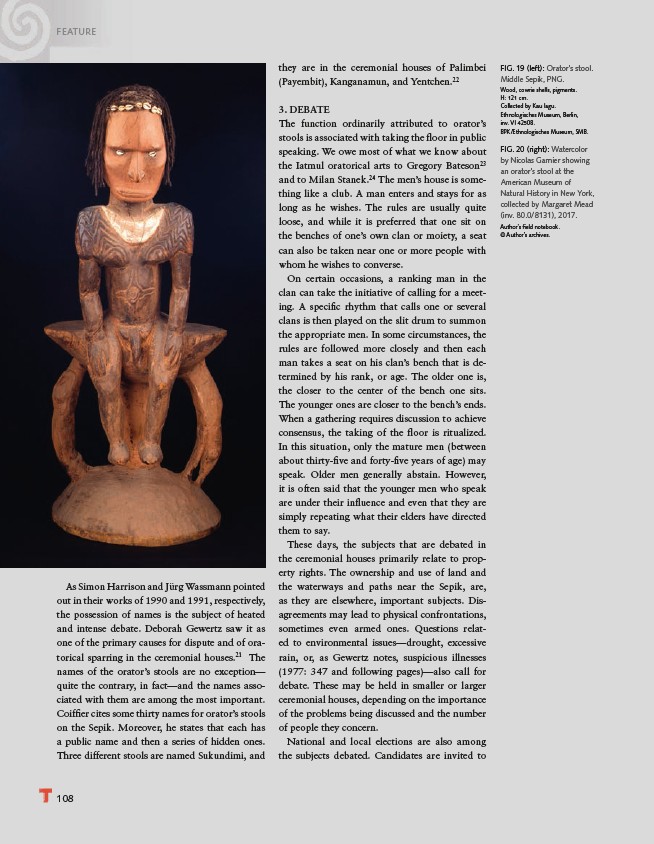

FIG. 19 (left): Orator’s stool.

Middle Sepik, PNG.

Wood, cowrie shells, pigments.

H: 121 cm.

Collected by Kau Iagu.

Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin,

inv. VI 42508.

BPK/Ethnologisches Museum, SMB.

FIG. 20 (right): Watercolor

by Nicolas Garnier showing

an orator’s stool at the

American Museum of

Natural History in New York,

collected by Margaret Mead

(inv. 80.0/8131), 2017.

Author’s fi eld notebook.

© Author’s archives.

As Simon Harrison and Jürg Wassmann pointed

out in their works of 1990 and 1991, respectively,

the possession of names is the subject of heated

and intense debate. Deborah Gewertz saw it as

one of the primary causes for dispute and of oratorical

sparring in the ceremonial houses.21 The

names of the orator’s stools are no exception—

quite the contrary, in fact—and the names associated

with them are among the most important.

Coiffi er cites some thirty names for orator’s stools

on the Sepik. Moreover, he states that each has

a public name and then a series of hidden ones.

Three different stools are named Sukundimi, and