FEATURE

130

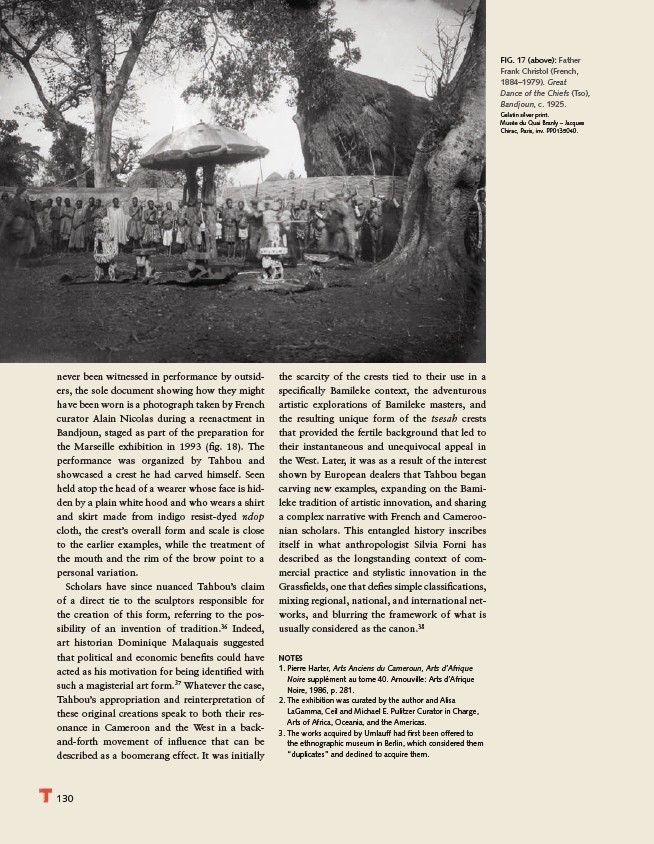

FIG. 17 (above): Father

Frank Christol (French,

1884–1979). Great

Dance of the Chiefs (Tso),

Bandjoun, c. 1925.

Gelatin silver print.

Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques

Chirac, Paris, inv. PP0135040.

never been witnessed in performance by outsiders,

the sole document showing how they might

have been worn is a photograph taken by French

curator Alain Nicolas during a reenactment in

Bandjoun, staged as part of the preparation for

the Marseille exhibition in 1993 (fi g. 18). The

performance was organized by Tahbou and

showcased a crest he had carved himself. Seen

held atop the head of a wearer whose face is hidden

by a plain white hood and who wears a shirt

and skirt made from indigo resist-dyed ndop

cloth, the crest’s overall form and scale is close

to the earlier examples, while the treatment of

the mouth and the rim of the brow point to a

personal variation.

Scholars have since nuanced Tahbou’s claim

of a direct tie to the sculptors responsible for

the creation of this form, referring to the possibility

of an invention of tradition.36 Indeed,

art historian Dominique Malaquais suggested

that political and economic benefi ts could have

acted as his motivation for being identifi ed with

such a magisterial art form.37 Whatever the case,

Tahbou’s appropriation and reinterpretation of

these original creations speak to both their resonance

in Cameroon and the West in a backand

forth movement of infl uence that can be

described as a boomerang effect. It was initially

the scarcity of the crests tied to their use in a

specifi cally Bamileke context, the adventurous

artistic explorations of Bamileke masters, and

the resulting unique form of the tsesah crests

that provided the fertile background that led to

their instantaneous and unequivocal appeal in

the West. Later, it was as a result of the interest

shown by European dealers that Tahbou began

carving new examples, expanding on the Bamileke

tradition of artistic innovation, and sharing

a complex narrative with French and Cameroonian

scholars. This entangled history inscribes

itself in what anthropologist Silvia Forni has

described as the longstanding context of commercial

practice and stylistic innovation in the

Grassfi elds, one that defi es simple classifi cations,

mixing regional, national, and international networks,

and blurring the framework of what is

usually considered as the canon.38

NOTES

1. Pierre Harter, Arts Anciens du Cameroun, Arts d’Afrique

Noire supplément au tome 40. Arnouville: Arts d’Afrique

Noire, 1986, p. 281.

2. The exhibition was curated by the author and Alisa

LaGamma, Ceil and Michael E. Pulitzer Curator in Charge,

Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

3. The works acquired by Umlauff had fi rst been offered to

the ethnographic museum in Berlin, which considered them

“duplicates” and declined to acquire them.