121

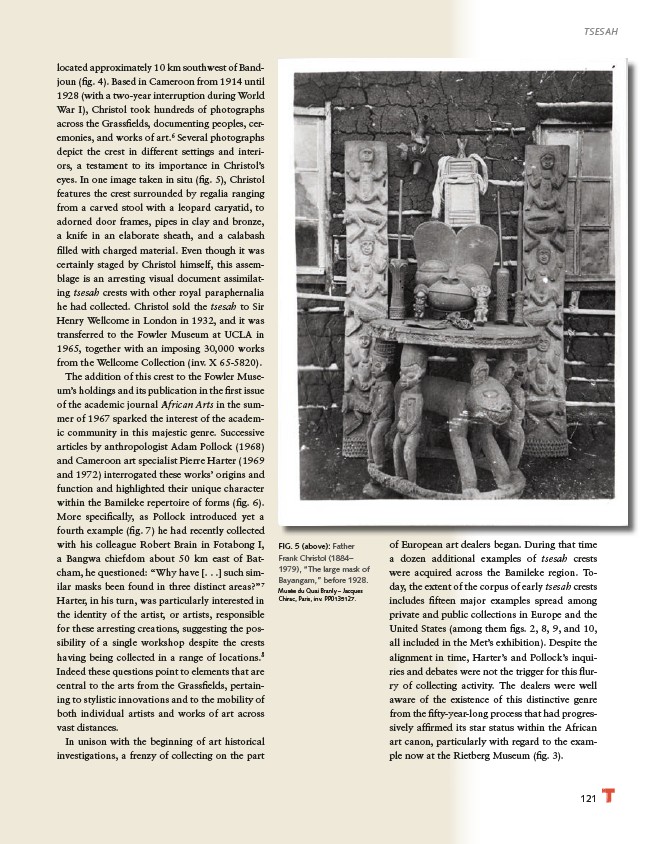

FIG. 5 (above): Father

Frank Christol (1884–

1979), “The large mask of

Bayangam,” before 1928.

Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques

Chirac, Paris, inv. PP0135127.

located approximately 10 km southwest of Bandjoun

(fi g. 4). Based in Cameroon from 1914 until

1928 (with a two-year interruption during World

War I), Christol took hundreds of photographs

across the Grassfi elds, documenting peoples, ceremonies,

and works of art.6 Several photographs

depict the crest in different settings and interiors,

a testament to its importance in Christol’s

eyes. In one image taken in situ (fi g. 5), Christol

features the crest surrounded by regalia ranging

from a carved stool with a leopard caryatid, to

adorned door frames, pipes in clay and bronze,

a knife in an elaborate sheath, and a calabash

fi lled with charged material. Even though it was

certainly staged by Christol himself, this assemblage

is an arresting visual document assimilating

tsesah crests with other royal paraphernalia

he had collected. Christol sold the tsesah to Sir

Henry Wellcome in London in 1932, and it was

transferred to the Fowler Museum at UCLA in

1965, together with an imposing 30,000 works

from the Wellcome Collection (inv. X 65-5820).

The addition of this crest to the Fowler Museum’s

holdings and its publication in the fi rst issue

of the academic journal African Arts in the summer

of 1967 sparked the interest of the academic

community in this majestic genre. Successive

articles by anthropologist Adam Pollock (1968)

and Cameroon art specialist Pierre Harter (1969

and 1972) interrogated these works’ origins and

function and highlighted their unique character

within the Bamileke repertoire of forms (fi g. 6).

More specifi cally, as Pollock introduced yet a

fourth example (fi g. 7) he had recently collected

with his colleague Robert Brain in Fotabong I,

a Bangwa chiefdom about 50 km east of Batcham,

he questioned: “Why have . . . such similar

masks been found in three distinct areas?”7

Harter, in his turn, was particularly interested in

the identity of the artist, or artists, responsible

for these arresting creations, suggesting the possibility

of a single workshop despite the crests

having being collected in a range of locations.8

Indeed these questions point to elements that are

central to the arts from the Grassfi elds, pertaining

to stylistic innovations and to the mobility of

both individual artists and works of art across

vast distances.

In unison with the beginning of art historical

investigations, a frenzy of collecting on the part

of European art dealers began. During that time

a dozen additional examples of tsesah crests

were acquired across the Bamileke region. Today,

the extent of the corpus of early tsesah crests

includes fi fteen major examples spread among

private and public collections in Europe and the

United States (among them fi gs. 2, 8, 9, and 10,

all included in the Met’s exhibition). Despite the

alignment in time, Harter’s and Pollock’s inquiries

and debates were not the trigger for this fl urry

of collecting activity. The dealers were well

aware of the existence of this distinctive genre

from the fi fty-year-long process that had progressively

affi rmed its star status within the African

art canon, particularly with regard to the example

now at the Rietberg Museum (fi g. 3).

TSESAH