TSESAH

125

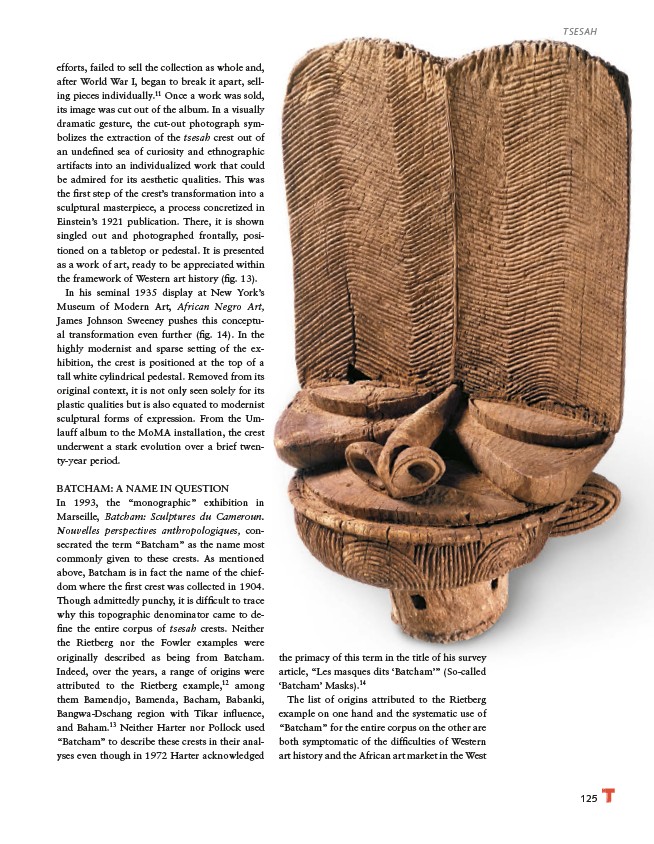

efforts, failed to sell the collection as whole and,

after World War I, began to break it apart, selling

pieces individually.11 Once a work was sold,

its image was cut out of the album. In a visually

dramatic gesture, the cut-out photograph symbolizes

the extraction of the tsesah crest out of

an undefined sea of curiosity and ethnographic

artifacts into an individualized work that could

be admired for its aesthetic qualities. This was

the first step of the crest’s transformation into a

sculptural masterpiece, a process concretized in

Einstein’s 1921 publication. There, it is shown

singled out and photographed frontally, positioned

on a tabletop or pedestal. It is presented

as a work of art, ready to be appreciated within

the framework of Western art history (fig. 13).

In his seminal 1935 display at New York’s

Museum of Modern Art, African Negro Art,

James Johnson Sweeney pushes this conceptual

transformation even further (fig. 14). In the

highly modernist and sparse setting of the exhibition,

the crest is positioned at the top of a

tall white cylindrical pedestal. Removed from its

original context, it is not only seen solely for its

plastic qualities but is also equated to modernist

sculptural forms of expression. From the Umlauff

album to the MoMA installation, the crest

underwent a stark evolution over a brief twenty

year period.

BATCHAM: A NAME IN QUESTION

In 1993, the “monographic” exhibition in

Marseille, Batcham: Sculptures du Cameroun.

Nouvelles perspectives anthropologiques, consecrated

the term “Batcham” as the name most

commonly given to these crests. As mentioned

above, Batcham is in fact the name of the chiefdom

where the first crest was collected in 1904.

Though admittedly punchy, it is difficult to trace

why this topographic denominator came to define

the entire corpus of tsesah crests. Neither

the Rietberg nor the Fowler examples were

originally described as being from Batcham.

Indeed, over the years, a range of origins were

attributed to the Rietberg example,12 among

them Bamendjo, Bamenda, Bacham, Babanki,

Bangwa-Dschang region with Tikar influence,

and Baham.13 Neither Harter nor Pollock used

“Batcham” to describe these crests in their analyses

even though in 1972 Harter acknowledged

the primacy of this term in the title of his survey

article, “Les masques dits ‘Batcham’” (So-called

‘Batcham’ Masks).14

The list of origins attributed to the Rietberg

example on one hand and the systematic use of

“Batcham” for the entire corpus on the other are

both symptomatic of the difficulties of Western

art history and the African art market in the West