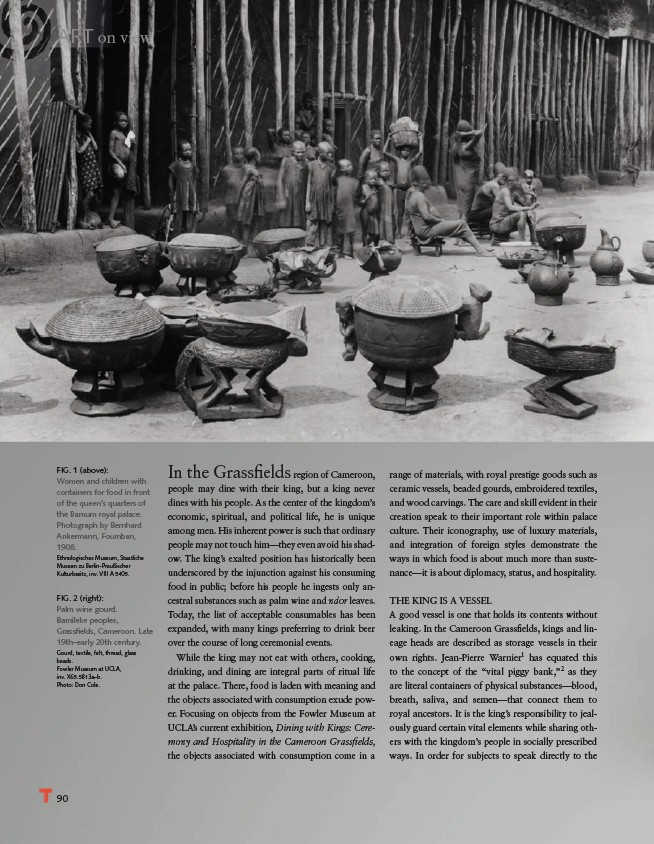

FIG. 1 (above):

Women and children with

containers for food in front

of the queen’s quarters of

the Bamum royal palace.

Photograph by Bernhard

Ankermann, Foumban,

1908.

Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche

Museen zu Berlin-Preußischer

Kulturbesitz, inv. VIII A 5405.

FIG. 2 (right):

Palm wine gourd.

Bamileke peoples,

Grassfi elds, Cameroon. Late

19th–early 20th century.

Gourd, textile, felt, thread, glass

beads.

Fowler Museum at UCLA,

inv. X65.5813a–b.

Photo: Don Cole.

90

In the Grassfi elds region of Cameroon,

people may dine with their king, but a king never

dines with his people. As the center of the kingdom’s

economic, spiritual, and political life, he is unique

among men. His inherent power is such that ordinary

people may not touch him—they even avoid his shadow.

The king’s exalted position has historically been

underscored by the injunction against his consuming

food in public; before his people he ingests only ancestral

substances such as palm wine and ndor leaves.

Today, the list of acceptable consumables has been

expanded, with many kings preferring to drink beer

over the course of long ceremonial events.

While the king may not eat with others, cooking,

drinking, and dining are integral parts of ritual life

at the palace. There, food is laden with meaning and

the objects associated with consumption exude power.

Focusing on objects from the Fowler Museum at

UCLA’s current exhibition, Dining with Kings: Ceremony

and Hospitality in the Cameroon Grassfi elds,

the objects associated with consumption come in a

range of materials, with royal prestige goods such as

ceramic vessels, beaded gourds, embroidered textiles,

and wood carvings. The care and skill evident in their

creation speak to their important role within palace

culture. Their iconography, use of luxury materials,

and integration of foreign styles demonstrate the

ways in which food is about much more than sustenance—

it is about diplomacy, status, and hospitality.

THE KING IS A VESSEL

A good vessel is one that holds its contents without

leaking. In the Cameroon Grassfi elds, kings and lineage

heads are described as storage vessels in their

own rights. Jean-Pierre Warnier1 has equated this

to the concept of the “vital piggy bank,”2 as they

are literal containers of physical substances—blood,

breath, saliva, and semen—that connect them to

royal ancestors. It is the king’s responsibility to jealously

guard certain vital elements while sharing others

with the kingdom’s people in socially prescribed

ways. In order for subjects to speak directly to the

ART on view