ORATOR’S STOOLS

115

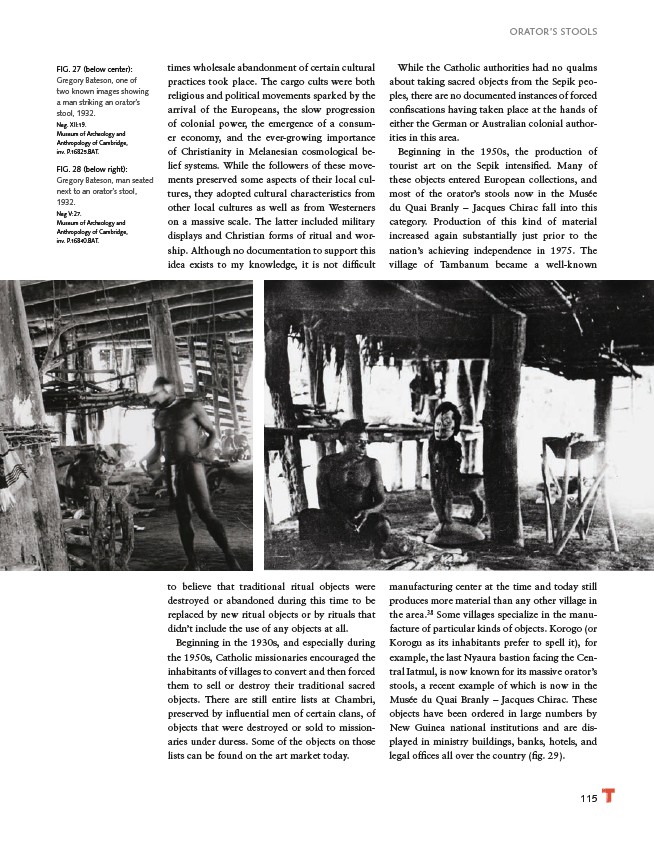

FIG. 27 (below center):

Gregory Bateson, one of

two known images showing

a man striking an orator’s

stool, 1932.

Neg. XII:19.

Museum of Archeology and

Anthropology of Cambridge,

inv. P.16825.BAT.

FIG. 28 (below right):

Gregory Bateson, man seated

next to an orator’s stool,

1932.

Neg V:27.

Museum of Archeology and

Anthropology of Cambridge,

inv. P.16840.BAT.

times wholesale abandonment of certain cultural

practices took place. The cargo cults were both

religious and political movements sparked by the

arrival of the Europeans, the slow progression

of colonial power, the emergence of a consumer

economy, and the ever-growing importance

of Christianity in Melanesian cosmological belief

systems. While the followers of these movements

preserved some aspects of their local cultures,

they adopted cultural characteristics from

other local cultures as well as from Westerners

on a massive scale. The latter included military

displays and Christian forms of ritual and worship.

Although no documentation to support this

idea exists to my knowledge, it is not difficult

to believe that traditional ritual objects were

destroyed or abandoned during this time to be

replaced by new ritual objects or by rituals that

didn’t include the use of any objects at all.

Beginning in the 1930s, and especially during

the 1950s, Catholic missionaries encouraged the

inhabitants of villages to convert and then forced

them to sell or destroy their traditional sacred

objects. There are still entire lists at Chambri,

preserved by influential men of certain clans, of

objects that were destroyed or sold to missionaries

under duress. Some of the objects on those

lists can be found on the art market today.

While the Catholic authorities had no qualms

about taking sacred objects from the Sepik peoples,

there are no documented instances of forced

confiscations having taken place at the hands of

either the German or Australian colonial authorities

in this area.

Beginning in the 1950s, the production of

tourist art on the Sepik intensified. Many of

these objects entered European collections, and

most of the orator’s stools now in the Musée

du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac fall into this

category. Production of this kind of material

increased again substantially just prior to the

nation’s achieving independence in 1975. The

village of Tambanum became a well-known

manufacturing center at the time and today still

produces more material than any other village in

the area.38 Some villages specialize in the manufacture

of particular kinds of objects. Korogo (or

Korogu as its inhabitants prefer to spell it), for

example, the last Nyaura bastion facing the Central

Iatmul, is now known for its massive orator’s

stools, a recent example of which is now in the

Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac. These

objects have been ordered in large numbers by

New Guinea national institutions and are displayed

in ministry buildings, banks, hotels, and

legal offices all over the country (fig. 29).