ART ON VIEW

ly rivalry among the Moche courts or the Maya

city-states, and this competiveness played out in

the visual arts as well.3 Such was the importance

of artists in the ancient Americas that they themselves

80

often became spoils of war. To note just one

instance, when the Incas conquered Chan Chan,

the capital of the Chimú state between AD 1000

and 1470, they kidnapped the metalsmiths and

pressed them into service in Cusco, their highland

capital.

Golden Kingdoms is arranged from south to

north, starting with Peru. This mirrors development

of goldworking in the Americas, which was

fi rst exploited in the Andes by the second millennium

BC. From there metallurgy gradually spread

north, reaching Central America by the fi rst centuries

AD and arriving in central Mexico before

the end of the fi rst millennium AD. Unlike in other

parts of the world, in the ancient Americas metalworking

fi rst developed in the context of ritual and

elite regalia rather than for tools, weapons, or currency.

Gold was likely the fi rst metal to be exploited

in the Andes, and it established a pattern that

metals were for use in rituals and that they were

closely associated with the supernatural realm.4

Gold is a soft, malleable material unsuitable for

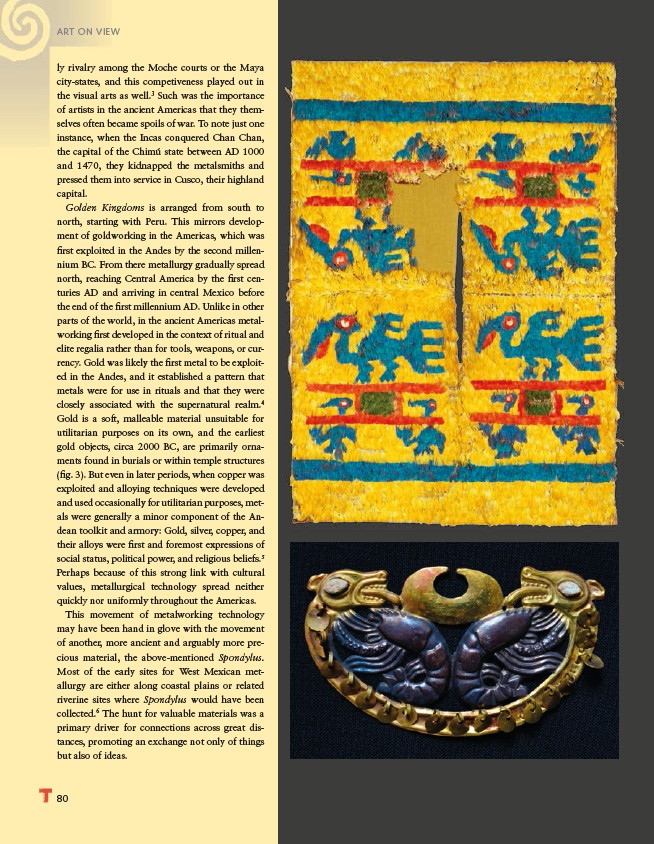

utilitarian purposes on its own, and the earliest

gold objects, circa 2000 BC, are primarily ornaments

found in burials or within temple structures

(fi g. 3). But even in later periods, when copper was

exploited and alloying techniques were developed

and used occasionally for utilitarian purposes, metals

were generally a minor component of the Andean

toolkit and armory: Gold, silver, copper, and

their alloys were fi rst and foremost expressions of

social status, political power, and religious beliefs.5

Perhaps because of this strong link with cultural

values, metallurgical technology spread neither

quickly nor uniformly throughout the Americas.

This movement of metalworking technology

may have been hand in glove with the movement

of another, more ancient and arguably more precious

material, the above-mentioned Spondylus.

Most of the early sites for West Mexican metallurgy

are either along coastal plains or related

riverine sites where Spondylus would have been

collected.6 The hunt for valuable materials was a

primary driver for connections across great distances,

promoting an exchange not only of things

but also of ideas.