86

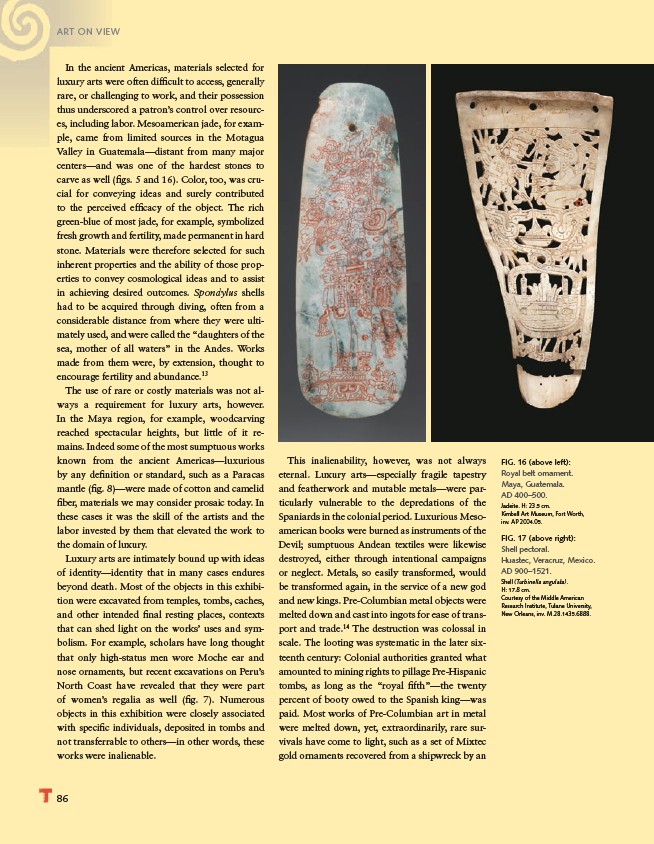

FIG. 16 (above left):

Royal belt ornament.

Maya, Guatemala.

AD 400–500.

Jadeite. H: 23.5 cm.

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth,

inv. AP 2004.05.

FIG. 17 (above right):

Shell pectoral.

Huastec, Veracruz, Mexico.

AD 900–1521.

Shell (Turbinella angulata).

H: 17.8 cm.

Courtesy of the Middle American

Research Institute, Tulane University,

New Orleans, inv. M.28.1435.6888.

ART ON VIEW

In the ancient Americas, materials selected for

luxury arts were often diffi cult to access, generally

rare, or challenging to work, and their possession

thus underscored a patron’s control over resources,

including labor. Mesoamerican jade, for example,

came from limited sources in the Motagua

Valley in Guatemala—distant from many major

centers—and was one of the hardest stones to

carve as well (fi gs. 5 and 16). Color, too, was crucial

for conveying ideas and surely contributed

to the perceived effi cacy of the object. The rich

green-blue of most jade, for example, symbolized

fresh growth and fertility, made permanent in hard

stone. Materials were therefore selected for such

inherent properties and the ability of those properties

to convey cosmological ideas and to assist

in achieving desired outcomes. Spondylus shells

had to be acquired through diving, often from a

considerable distance from where they were ultimately

used, and were called the “daughters of the

sea, mother of all waters” in the Andes. Works

made from them were, by extension, thought to

encourage fertility and abundance.13

The use of rare or costly materials was not always

a requirement for luxury arts, however.

In the Maya region, for example, woodcarving

reached spectacular heights, but little of it remains.

Indeed some of the most sumptuous works

known from the ancient Americas—luxurious

by any defi nition or standard, such as a Paracas

mantle (fi g. 8)—were made of cotton and camelid

fi ber, materials we may consider prosaic today. In

these cases it was the skill of the artists and the

labor invested by them that elevated the work to

the domain of luxury.

Luxury arts are intimately bound up with ideas

of identity—identity that in many cases endures

beyond death. Most of the objects in this exhibition

were excavated from temples, tombs, caches,

and other intended fi nal resting places, contexts

that can shed light on the works’ uses and symbolism.

For example, scholars have long thought

that only high-status men wore Moche ear and

nose ornaments, but recent excavations on Peru’s

North Coast have revealed that they were part

of women’s regalia as well (fi g. 7). Numerous

objects in this exhibition were closely associated

with specifi c individuals, deposited in tombs and

not transferrable to others—in other words, these

works were inalienable.

This inalienability, however, was not always

eternal. Luxury arts—especially fragile tapestry

and featherwork and mutable metals—were particularly

vulnerable to the depredations of the

Spaniards in the colonial period. Luxurious Mesoamerican

books were burned as instruments of the

Devil; sumptuous Andean textiles were likewise

destroyed, either through intentional campaigns

or neglect. Metals, so easily transformed, would

be transformed again, in the service of a new god

and new kings. Pre-Columbian metal objects were

melted down and cast into ingots for ease of transport

and trade.14 The destruction was colossal in

scale. The looting was systematic in the later sixteenth

century: Colonial authorities granted what

amounted to mining rights to pillage Pre-Hispanic

tombs, as long as the “royal fi fth”—the twenty

percent of booty owed to the Spanish king—was

paid. Most works of Pre-Columbian art in metal

were melted down, yet, extraordinarily, rare survivals

have come to light, such as a set of Mixtec

gold ornaments recovered from a shipwreck by an