84

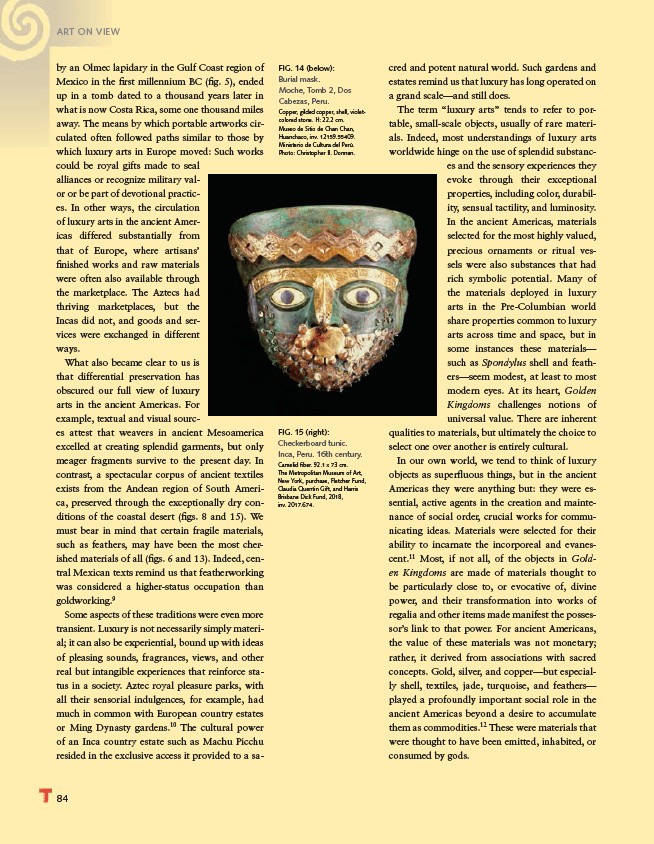

FIG. 14 (below):

Burial mask.

Moche, Tomb 2, Dos

Cabezas, Peru.

Copper, gilded copper, shell, violetcolored

stone. H: 22.2 cm.

Museo de Sitio de Chan Chan,

Huanchaco, inv. 12159.55409.

Ministerio de Cultura del Perú.

Photo: Christopher B. Donnan.

FIG. 15 (right):

Checkerboard tunic.

Inca, Peru. 16th century.

Camelid fi ber. 92.1 x 73 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

New York, purchase, Fletcher Fund,

Claudia Quentin Gift, and Harris

Brisbane Dick Fund, 2018,

inv. 2017.674.

ART ON VIEW

by an Olmec lapidary in the Gulf Coast region of

Mexico in the fi rst millennium BC (fi g. 5), ended

up in a tomb dated to a thousand years later in

what is now Costa Rica, some one thousand miles

away. The means by which portable artworks circulated

often followed paths similar to those by

which luxury arts in Europe moved: Such works

could be royal gifts made to seal

alliances or recognize military valor

or be part of devotional practices.

In other ways, the circulation

of luxury arts in the ancient Americas

differed substantially from

that of Europe, where artisans’

fi nished works and raw materials

were often also available through

the marketplace. The Aztecs had

thriving marketplaces, but the

Incas did not, and goods and services

were exchanged in different

ways.

What also became clear to us is

that differential preservation has

obscured our full view of luxury

arts in the ancient Americas. For

example, textual and visual sources

attest that weavers in ancient Mesoamerica

excelled at creating splendid garments, but only

meager fragments survive to the present day. In

contrast, a spectacular corpus of ancient textiles

exists from the Andean region of South America,

preserved through the exceptionally dry conditions

of the coastal desert (fi gs. 8 and 15). We

must bear in mind that certain fragile materials,

such as feathers, may have been the most cherished

materials of all (fi gs. 6 and 13). Indeed, central

Mexican texts remind us that featherworking

was considered a higher-status occupation than

goldworking.9

Some aspects of these traditions were even more

transient. Luxury is not necessarily simply material;

it can also be experiential, bound up with ideas

of pleasing sounds, fragrances, views, and other

real but intangible experiences that reinforce status

in a society. Aztec royal pleasure parks, with

all their sensorial indulgences, for example, had

much in common with European country estates

or Ming Dynasty gardens.10 The cultural power

of an Inca country estate such as Machu Picchu

resided in the exclusive access it provided to a sacred

and potent natural world. Such gardens and

estates remind us that luxury has long operated on

a grand scale—and still does.

The term “luxury arts” tends to refer to portable,

small-scale objects, usually of rare materials.

Indeed, most understandings of luxury arts

worldwide hinge on the use of splendid substances

and the sensory experiences they

evoke through their exceptional

properties, including color, durability,

sensual tactility, and luminosity.

In the ancient Americas, materials

selected for the most highly valued,

precious ornaments or ritual vessels

were also substances that had

rich symbolic potential. Many of

the materials deployed in luxury

arts in the Pre-Columbian world

share properties common to luxury

arts across time and space, but in

some instances these materials—

such as Spondylus shell and feathers—

seem modest, at least to most

modern eyes. At its heart, Golden

Kingdoms challenges notions of

universal value. There are inherent

qualities to materials, but ultimately the choice to

select one over another is entirely cultural.

In our own world, we tend to think of luxury

objects as superfl uous things, but in the ancient

Americas they were anything but: they were essential,

active agents in the creation and maintenance

of social order, crucial works for communicating

ideas. Materials were selected for their

ability to incarnate the incorporeal and evanescent.

11 Most, if not all, of the objects in Golden

Kingdoms are made of materials thought to

be particularly close to, or evocative of, divine

power, and their transformation into works of

regalia and other items made manifest the possessor’s

link to that power. For ancient Americans,

the value of these materials was not monetary;

rather, it derived from associations with sacred

concepts. Gold, silver, and copper—but especially

shell, textiles, jade, turquoise, and feathers—

played a profoundly important social role in the

ancient Americas beyond a desire to accumulate

them as commodities.12 These were materials that

were thought to have been emitted, inhabited, or

consumed by gods.