WESTERN NORTH AMERICA

sculpture of Jesus and Saint John, for

instance, depicts the saint as the male

“bride” of Christ, while male Hemba

ancestor fi gures refer to female generative

75

powers.

Visitors are encouraged to consider

the pairings and groups critically and

to reach their own conclusions about

the ways the objects relate to each

other. The wall texts and the object labels,

as well as the catalog, are starting

points for learning more about the works on display.

The information they provide is not meant

to be a defi nitive statement about what the objects

are or a complete explanation of everything that is

known about them. There are always more stories

to tell and more questions than can be answered.

In recent years, interest has focused on how

museums discuss the provenance of the works in

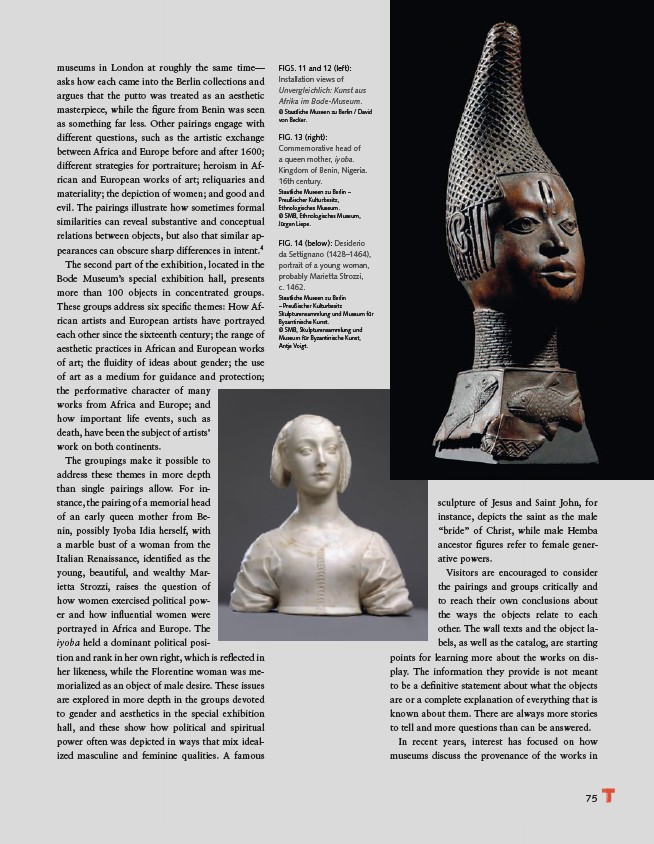

FIGS. 11 and 12 (left):

Installation views of

Unvergleichlich: Kunst aus

Afrika im Bode-Museum.

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / David

von Becker.

FIG. 13 (right):

Commemorative head of

a queen mother, iyoba.

Kingdom of Benin, Nigeria.

16th century.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin –

Preußischer Kulturbesitz,

Ethnologisches Museum.

© SMB, Ethnologisches Museum,

Jürgen Liepe.

FIG. 14 (below): Desiderio

da Settignano (1428–1464),

portrait of a young woman,

probably Marietta Strozzi,

c. 1462.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

– Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Skulpturensammlung und Museum für

Byzantinische Kunst.

© SMB, Skulpturensammlung und

Museum für Byzantinische Kunst,

Antje Voigt.

museums in London at roughly the same time—

asks how each came into the Berlin collections and

argues that the putto was treated as an aesthetic

masterpiece, while the fi gure from Benin was seen

as something far less. Other pairings engage with

different questions, such as the artistic exchange

between Africa and Europe before and after 1600;

different strategies for portraiture; heroism in African

and European works of art; reliquaries and

materiality; the depiction of women; and good and

evil. The pairings illustrate how sometimes formal

similarities can reveal substantive and conceptual

relations between objects, but also that similar appearances

can obscure sharp differences in intent.4

The second part of the exhibition, located in the

Bode Museum’s special exhibition hall, presents

more than 100 objects in concentrated groups.

These groups address six specifi c themes: How African

artists and European artists have portrayed

each other since the sixteenth century; the range of

aesthetic practices in African and European works

of art; the fl uidity of ideas about gender; the use

of art as a medium for guidance and protection;

the performative character of many

works from Africa and Europe; and

how important life events, such as

death, have been the subject of artists’

work on both continents.

The groupings make it possible to

address these themes in more depth

than single pairings allow. For instance,

the pairing of a memorial head

of an early queen mother from Benin,

possibly Iyoba Idia herself, with

a marble bust of a woman from the

Italian Renaissance, identifi ed as the

young, beautiful, and wealthy Marietta

Strozzi, raises the question of

how women exercised political power

and how infl uential women were

portrayed in Africa and Europe. The

iyoba held a dominant political position

and rank in her own right, which is refl ected in

her likeness, while the Florentine woman was memorialized

as an object of male desire. These issues

are explored in more depth in the groups devoted

to gender and aesthetics in the special exhibition

hall, and these show how political and spiritual

power often was depicted in ways that mix idealized

masculine and feminine qualities. A famous