118

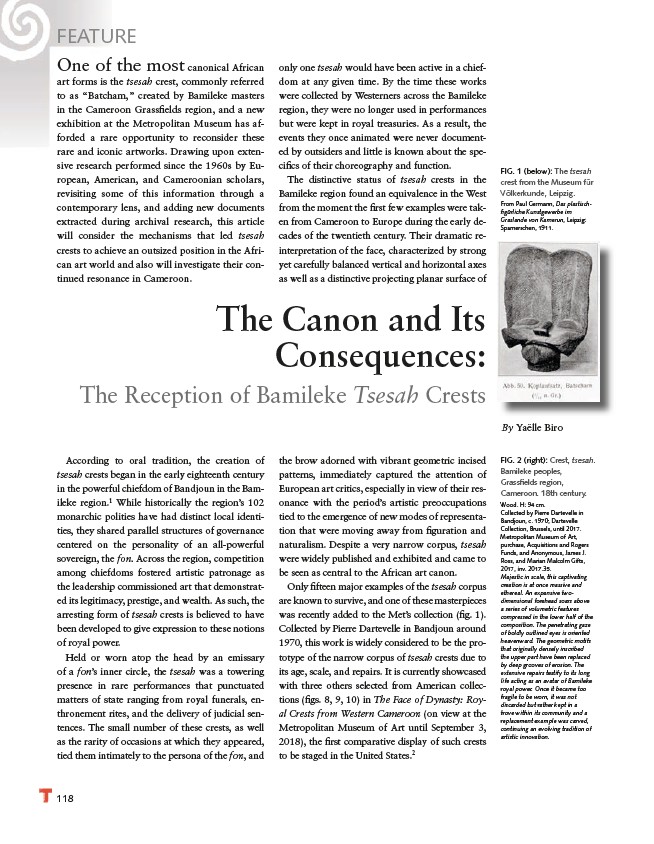

FIG. 1 (below): The tsesah

crest from the Museum für

Völkerkunde, Leipzig.

From Paul Germann, Das plastischfi

gürliche Kunstgewerbe im

Graslande von Kamerun, Leipzig:

Spamerschen, 1911.

According to oral tradition, the creation of

tsesah crests began in the early eighteenth century

in the powerful chiefdom of Bandjoun in the Bamileke

region.1 While historically the region’s 102

monarchic polities have had distinct local identities,

they shared parallel structures of governance

centered on the personality of an all-powerful

sovereign, the fon. Across the region, competition

among chiefdoms fostered artistic patronage as

the leadership commissioned art that demonstrated

its legitimacy, prestige, and wealth. As such, the

arresting form of tsesah crests is believed to have

been developed to give expression to these notions

of royal power.

Held or worn atop the head by an emissary

of a fon’s inner circle, the tsesah was a towering

presence in rare performances that punctuated

matters of state ranging from royal funerals, enthronement

rites, and the delivery of judicial sentences.

The small number of these crests, as well

as the rarity of occasions at which they appeared,

tied them intimately to the persona of the fon, and

only one tsesah would have been active in a chiefdom

at any given time. By the time these works

were collected by Westerners across the Bamileke

region, they were no longer used in performances

but were kept in royal treasuries. As a result, the

events they once animated were never documented

by outsiders and little is known about the specifi

cs of their choreography and function.

The distinctive status of tsesah crests in the

Bamileke region found an equivalence in the West

from the moment the fi rst few examples were taken

from Cameroon to Europe during the early decades

of the twentieth century. Their dramatic reinterpretation

of the face, characterized by strong

yet carefully balanced vertical and horizontal axes

as well as a distinctive projecting planar surface of

the brow adorned with vibrant geometric incised

patterns, immediately captured the attention of

European art critics, especially in view of their resonance

with the period’s artistic preoccupations

tied to the emergence of new modes of representation

that were moving away from fi guration and

naturalism. Despite a very narrow corpus, tsesah

were widely published and exhibited and came to

be seen as central to the African art canon.

Only fi fteen major examples of the tsesah corpus

are known to survive, and one of these masterpieces

was recently added to the Met’s collection (fi g. 1).

Collected by Pierre Dartevelle in Bandjoun around

1970, this work is widely considered to be the prototype

of the narrow corpus of tsesah crests due to

its age, scale, and repairs. It is currently showcased

with three others selected from American collections

(fi gs. 8, 9, 10) in The Face of Dynasty: Royal

Crests from Western Cameroon (on view at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art until September 3,

2018), the fi rst comparative display of such crests

to be staged in the United States.2

FIG. 2 (right): Crest, tsesah.

Bamileke peoples,

Grassfi elds region,

Cameroon. 18th century.

Wood. H: 94 cm.

Collected by Pierre Dartevelle in

Bandjoun, c. 1970; Dartevelle

Collection, Brussels, until 2017.

Metropolitan Museum of Art,

purchase, Acquisitions and Rogers

Funds, and Anonymous, James J.

Ross, and Marian Malcolm Gifts,

2017, inv. 2017.35.

Majestic in scale, this captivating

creation is at once massive and

ethereal. An expansive twodimensional

forehead soars above

a series of volumetric features

compressed in the lower half of the

composition. The penetrating gaze

of boldly outlined eyes is oriented

heavenward. The geometric motifs

that originally densely inscribed

the upper part have been replaced

by deep grooves of erosion. The

extensive repairs testify to its long

life acting as an avatar of Bamileke

royal power. Once it became too

fragile to be worn, it was not

discarded but rather kept in a

trove within its community and a

replacement example was carved,

continuing an evolving tradition of

artistic innovation.

One of the most canonical African

art forms is the tsesah crest, commonly referred

to as “Batcham,” created by Bamileke masters

in the Cameroon Grassfi elds region, and a new

exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum has afforded

a rare opportunity to reconsider these

rare and iconic artworks. Drawing upon extensive

research performed since the 1960s by European,

American, and Cameroonian scholars,

revisiting some of this information through a

contemporary lens, and adding new documents

extracted during archival research, this article

will consider the mechanisms that led tsesah

crests to achieve an outsized position in the African

art world and also will investigate their continued

resonance in Cameroon.

By Yaëlle Biro

FEATURE

The Canon and Its

Consequences:

The Reception of Bamileke Tsesah Crests