TSESAH

As such, it visually expressed the statement “So

and so is gone, but he is back,” in a manner that

echoes the establishment of a new king in the

French monarchy: “The king is dead, long live

the king.”

A BOOMERANG EFFECT

Tahbou’s own activities as a carver provide a

fascinating extension to this history of evolving

creativity and continued innovation, fi rmly anchored

in the Grassfi elds as a vibrant marketplace

for a range of art forms.32 Indeed, Harter

described how in the early 1970s, seeing tsesah

crests actively sought after by European dealers,

Tahbou himself began producing examples (fi g.

19).33 While a number of these entered the art

market, others were in the Bandjoun royal treasury,

34 which has since been transformed into a

museum.35 Furthermore, as tsesah crests have

129

testify to the transmission of knowledge over

generations, and they attest to these artists’ freedom

and creative innovations in interpreting a

continually evolving genre.

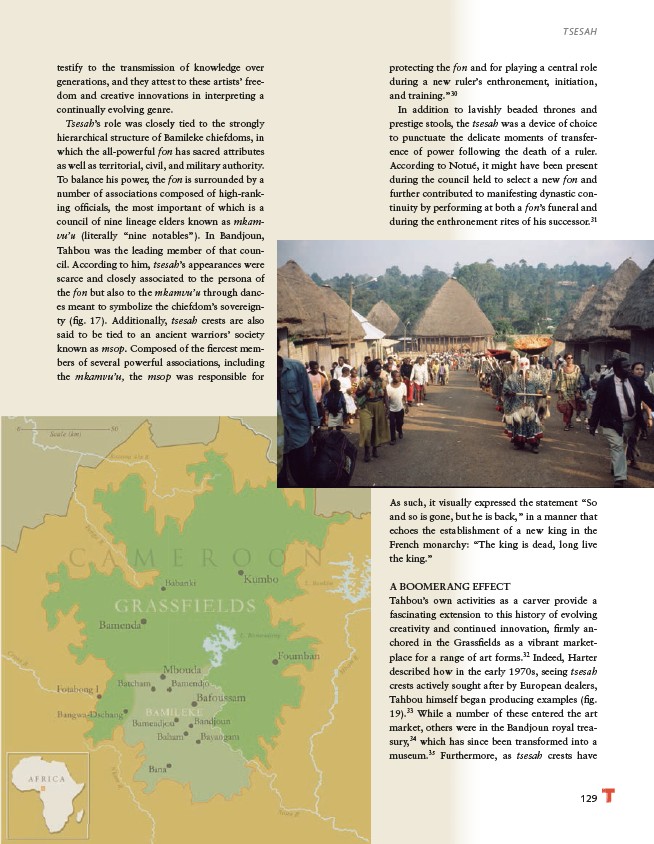

Tsesah’s role was closely tied to the strongly

hierarchical structure of Bamileke chiefdoms, in

which the all-powerful fon has sacred attributes

as well as territorial, civil, and military authority.

To balance his power, the fon is surrounded by a

number of associations composed of high-ranking

offi cials, the most important of which is a

council of nine lineage elders known as mkamvu’u

(literally “nine notables”). In Bandjoun,

Tahbou was the leading member of that council.

According to him, tsesah’s appearances were

scarce and closely associated to the persona of

the fon but also to the mkamvu’u through dances

meant to symbolize the chiefdom’s sovereignty

(fi g. 17). Additionally, tsesah crests are also

said to be tied to an ancient warriors’ society

known as msop. Composed of the fi ercest members

of several powerful associations, including

the mkamvu’u, the msop was responsible for

protecting the fon and for playing a central role

during a new ruler’s enthronement, initiation,

and training.”30

In addition to lavishly beaded thrones and

prestige stools, the tsesah was a device of choice

to punctuate the delicate moments of transference

of power following the death of a ruler.

According to Notué, it might have been present

during the council held to select a new fon and

further contributed to manifesting dynastic continuity

by performing at both a fon’s funeral and

during the enthronement rites of his successor.31