TSESAH

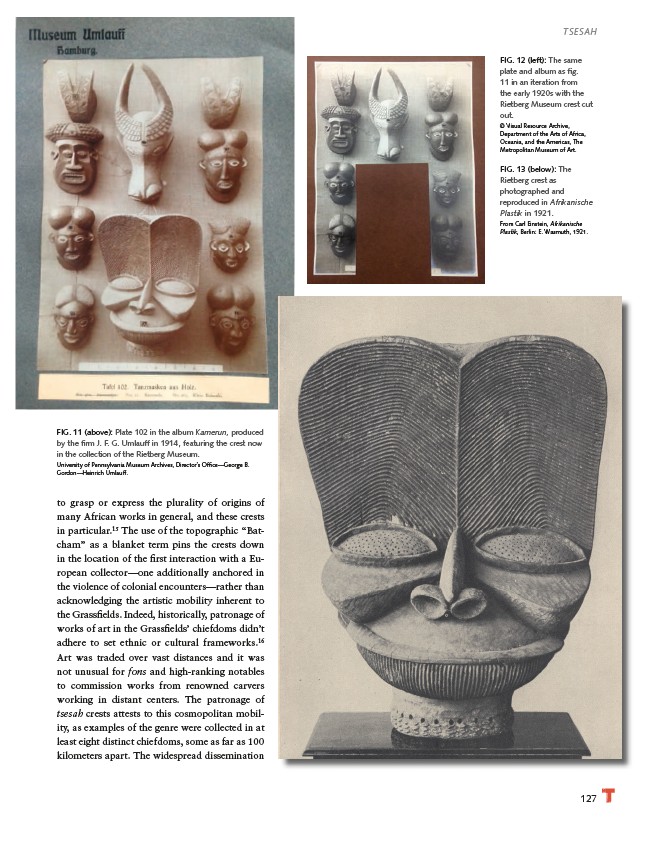

FIG. 12 (left): The same

plate and album as fi g.

11 in an iteration from

the early 1920s with the

Rietberg Museum crest cut

out.

© Visual Resource Archive,

Department of the Arts of Africa,

Oceania, and the Americas, The

Metropolitan Museum of Art.

FIG. 13 (below): The

Rietberg crest as

photographed and

reproduced in Afrikanische

Plastik in 1921.

From Carl Einstein, Afrikanische

Plastik, Berlin: E. Wasmuth, 1921.

127

FIG. 11 (above): Plate 102 in the album Kamerun, produced

by the fi rm J. F. G. Umlauff in 1914, featuring the crest now

in the collection of the Rietberg Museum.

University of Pennsylvania Museum Archives, Director’s Offi ce—George B.

Gordon—Heinrich Umlauff.

to grasp or express the plurality of origins of

many African works in general, and these crests

in particular.15 The use of the topographic “Batcham”

as a blanket term pins the crests down

in the location of the fi rst interaction with a European

collector—one additionally anchored in

the violence of colonial encounters—rather than

acknowledging the artistic mobility inherent to

the Grassfi elds. Indeed, historically, patronage of

works of art in the Grassfi elds’ chiefdoms didn’t

adhere to set ethnic or cultural frameworks.16

Art was traded over vast distances and it was

not unusual for fons and high-ranking notables

to commission works from renowned carvers

working in distant centers. The patronage of

tsesah crests attests to this cosmopolitan mobility,

as examples of the genre were collected in at

least eight distinct chiefdoms, some as far as 100

kilometers apart. The widespread dissemination