DINING WITH KINGS

indicates the clear social connections between the

container, procreation, and the concept of royalty. In

some instances, the link is even more pronounced,

as in cases when the iconographic elements on pots

directly reference royal power. Water pots made by

skilled Babessi ceramicists are sometimes adorned

with a range of motifs, such as snakes and spiders,

which are symbolic references of the authority of the

palace and ancestors. The serpent is an example of

the king’s power to transform into an animal and

acts as a reminder of his royal authority, while the

spider is used in divination practices that allow communication

with spiritual and ancestral forces (fi g.

10).

DIPLOMACY AND THE ROYAL TABLE

We are fortunate to be able to include in this exhibition

a tablecloth made during the reign of the

Bamum king Ibrahim Njoya. In 1931, the Chicago

born writer Mary Hastings Bradley (fi g. 5) traveled

through Cameroon, and among the places she

stopped was Foumban,7 home to King Njoya, who

had a long history of interactions with Europeans.

Missionaries and members of the German military

had taken up residence in the Bamum kingdom by

the fi rst decade of the twentieth century and had

brought with them new styles of clothing and textiles.

King Njoya soon began to wear German military

dress for select public appearances. Rather than

rely on imported fabric, he formed his own textile

workshop in 1910. With over three hundred looms

at work by 1912, textile production became a large

part of the palace’s artistic output,8 along with ceramics,

metalwork, and woodcarving. A portion of

this production was devoted to the fabrication of

gifts for King Njoya’s many foreign visitors.

When Hastings Bradley visited Foumban, King

Njoya had been on the throne for over forty years.

He had witnessed German colonial rule, the shifting

of power to the French, and the growing infl uence

of Christianity. Njoya maintained his leadership

through all of this, in no small part because of his

willingness to embrace the ideas outsiders brought

to his kingdom. He also never missed an opportunity

to act as a gracious host, indulging his visitors’ desire

for high-quality objects through gifts.9 These gifts

served as ambassadors for the Bamum kingdom in

Europe and elsewhere. King Njoya’s diplomatic tactics

are represented by the gift he made to Hastings

Bradley of an embroidered tablecloth and napkins

(fi gs. 4 and 6).

While the practice of using a tablecloth may have

come from earlier German visitors to King Ibrahim

Njoya’s court, the tablecloths the palace produced

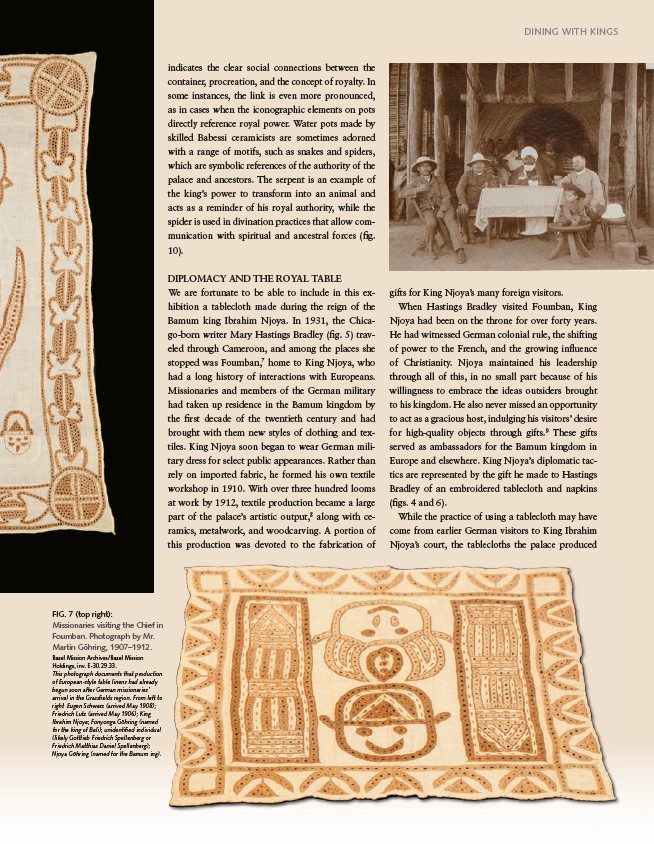

FIG. 7 (top right):

Missionaries visiting the Chief in

Foumban. Photograph by Mr.

Martin Göhring, 1907–1912.

Basel Mission Archives/Basel Mission

Holdings, inv. E-30.29.33.

This photograph documents that production

of European-style table linens had already

begun soon after German missionaries’

arrival in the Grassfi elds region. From left to

right: Eugen Schwarz (arrived May 1908);

Friedrich Lutz (arrived May 1906); King

Ibrahim Njoya; Fonyonga Göhring (named

for the king of Bali); unidentifi ed individual

(likely Gottlieb Friedrich Spellenberg or

Friedrich Matthias Daniel Spellenberg);

Njoya Göhring (named for the Bamum ing).