135

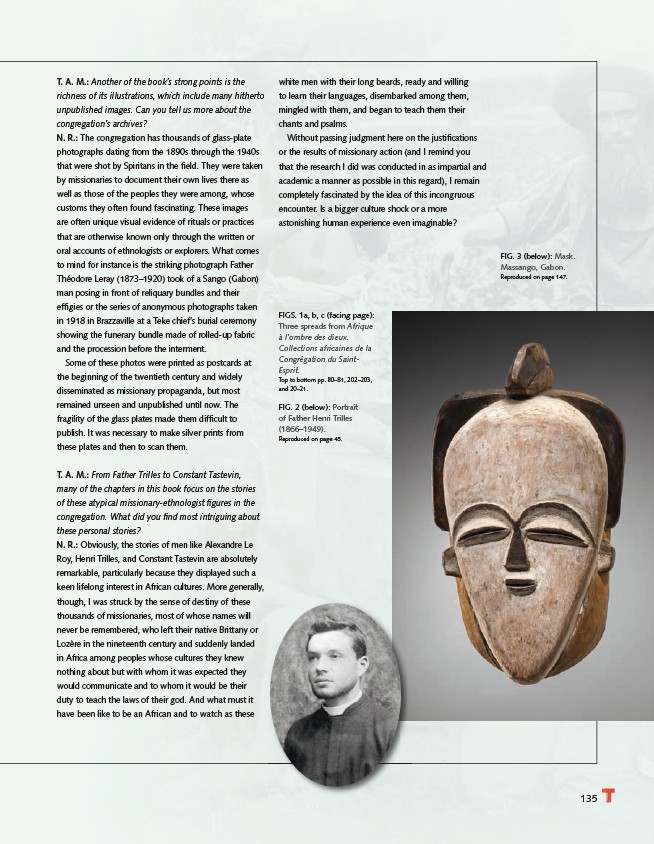

FIG. 3 (below): Mask.

Massango, Gabon.

Reproduced on page 147.

FIGS. 1a, b, c (facing page):

Three spreads from Afrique

à l’ombre des dieux.

Collections africaines de la

Congrégation du Saint-

Esprit.

Top to bottom pp. 80–81, 202–203,

and 20–21.

FIG. 2 (below): Portrait

of Father Henri Trilles

(1866–1949).

Reproduced on page 45.

T. A. M.: Another of the book’s strong points is the

richness of its illustrations, which include many hitherto

unpublished images. Can you tell us more about the

congregation’s archives?

N. R.: The congregation has thousands of glass-plate

photographs dating from the 1890s through the 1940s

that were shot by Spiritans in the fi eld. They were taken

by missionaries to document their own lives there as

well as those of the peoples they were among, whose

customs they often found fascinating. These images

are often unique visual evidence of rituals or practices

that are otherwise known only through the written or

oral accounts of ethnologists or explorers. What comes

to mind for instance is the striking photograph Father

Théodore Leray (1873–1920) took of a Sango (Gabon)

man posing in front of reliquary bundles and their

effi gies or the series of anonymous photographs taken

in 1918 in Brazzaville at a Teke chief’s burial ceremony

showing the funerary bundle made of rolled-up fabric

and the procession before the interment.

Some of these photos were printed as postcards at

the beginning of the twentieth century and widely

disseminated as missionary propaganda, but most

remained unseen and unpublished until now. The

fragility of the glass plates made them diffi cult to

publish. It was necessary to make silver prints from

these plates and then to scan them.

T. A. M.: From Father Trilles to Constant Tastevin,

many of the chapters in this book focus on the stories

of these atypical missionary-ethnologist fi gures in the

congregation. What did you fi nd most intriguing about

these personal stories?

N. R.: Obviously, the stories of men like Alexandre Le

Roy, Henri Trilles, and Constant Tastevin are absolutely

remarkable, particularly because they displayed such a

keen lifelong interest in African cultures. More generally,

though, I was struck by the sense of destiny of these

thousands of missionaries, most of whose names will

never be remembered, who left their native Brittany or

Lozère in the nineteenth century and suddenly landed

in Africa among peoples whose cultures they knew

nothing about but with whom it was expected they

would communicate and to whom it would be their

duty to teach the laws of their god. And what must it

have been like to be an African and to watch as these

white men with their long beards, ready and willing

to learn their languages, disembarked among them,

mingled with them, and began to teach them their

chants and psalms.

Without passing judgment here on the justifi cations

or the results of missionary action (and I remind you

that the research I did was conducted in as impartial and

academic a manner as possible in this regard), I remain

completely fascinated by the idea of this incongruous

encounter. Is a bigger culture shock or a more

astonishing human experience even imaginable?