73

Scontornare mantenendo ombre

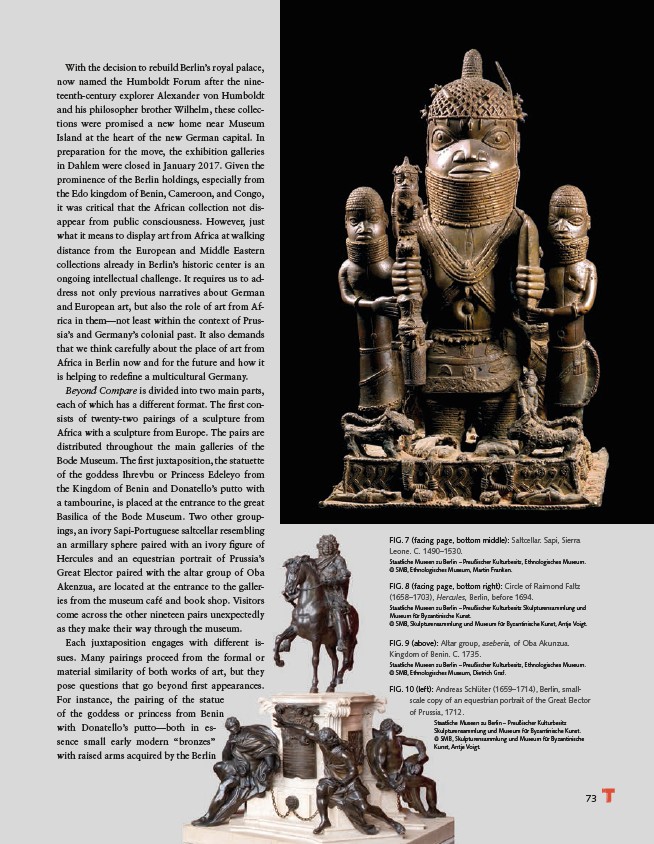

FIG. 7 (facing page, bottom middle): Saltcellar. Sapi, Sierra

Leone. C. 1490–1530.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Ethnologisches Museum.

© SMB, Ethnologisches Museum, Martin Franken.

FIG. 8 (facing page, bottom right): Circle of Raimond Faltz

(1658–1703), Hercules, Berlin, before 1694.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz Skulpturensammlung und

Museum für Byzantinische Kunst.

© SMB, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Antje Voigt.

FIG. 9 (above): Altar group, aseberia, of Oba Akunzua.

Kingdom of Benin. C. 1735.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Ethnologisches Museum.

© SMB, Ethnologisches Museum, Dietrich Graf.

FIG. 10 (left): Andreas Schlüter (1659–1714), Berlin, smallscale

copy of an equestrian portrait of the Great Elector

of Prussia, 1712.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst.

© SMB, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische

Kunst, Antje Voigt.

With the decision to rebuild Berlin’s royal palace,

now named the Humboldt Forum after the nineteenth

century explorer Alexander von Humboldt

and his philosopher brother Wilhelm, these collections

were promised a new home near Museum

Island at the heart of the new German capital. In

preparation for the move, the exhibition galleries

in Dahlem were closed in January 2017. Given the

prominence of the Berlin holdings, especially from

the Edo kingdom of Benin, Cameroon, and Congo,

it was critical that the African collection not disappear

from public consciousness. However, just

what it means to display art from Africa at walking

distance from the European and Middle Eastern

collections already in Berlin’s historic center is an

ongoing intellectual challenge. It requires us to address

not only previous narratives about German

and European art, but also the role of art from Africa

in them—not least within the context of Prussia’s

and Germany’s colonial past. It also demands

that we think carefully about the place of art from

Africa in Berlin now and for the future and how it

is helping to redefine a multicultural Germany.

Beyond Compare is divided into two main parts,

each of which has a different format. The first consists

of twenty-two pairings of a sculpture from

Africa with a sculpture from Europe. The pairs are

distributed throughout the main galleries of the

Bode Museum. The first juxtaposition, the statuette

of the goddess Ihrevbu or Princess Edeleyo from

the Kingdom of Benin and Donatello’s putto with

a tambourine, is placed at the entrance to the great

Basilica of the Bode Museum. Two other groupings,

an ivory Sapi-Portuguese saltcellar resembling

an armillary sphere paired with an ivory figure of

Hercules and an equestrian portrait of Prussia’s

Great Elector paired with the altar group of Oba

Akenzua, are located at the entrance to the galleries

from the museum café and book shop. Visitors

come across the other nineteen pairs unexpectedly

as they make their way through the museum.

Each juxtaposition engages with different issues.

Many pairings proceed from the formal or

material similarity of both works of art, but they

pose questions that go beyond first appearances.

For instance, the pairing of the statue

of the goddess or princess from Benin

with Donatello’s putto—both in essence

small early modern “bronzes”

with raised arms acquired by the Berlin