TSESAH

21. Jean-Paul Notué. “La symbolique des arts bamiléké

(Ouest-Cameroun) : approche historique et

anthropologique,” thèse de doctorat, Paris I, 4 vol., 1988;

Notué 1993; Notué and Louis Perrois, Rois et sculpteurs

de l’Ouest Cameroun. La panthère et la mygale, Paris:

Karthala, Orstom, 1997; Notué and Triaca 2005.

22. For more information on Tahbou, see Notué and Triaca

2005, pp. 104–106.

23. Notué 1993, p. 102.

24. On the concept of pi, see Notué 1993, pp. 64–65.

25. Harter 1972, pp. 32–34.

26. Notué 1993, p. 102.

27. Harter created a photographic dossier of known examples,

which is now held in the collection of the Musée du Quai

Branly – Jacques Chirac.

28. Harter 1969, p. 413.

29. Lorenz Homberger (ed.), Cameroon: Art and Kings, Zurich:

Museum Rietberg, 2008, p. 176.

30. Notué 1993, p. 98.

31. Notué 1993, p. 60.

32. See Silvia Forni’s research, most recently “Masks on

the Move. Defying Genres, Styles, and Traditions in the

Cameroonian Grassfi elds,” African Arts, Summer 2016, vol.

49, no. 2, pp. 38–53.

33. Harter 1972, p. 32. Harter even detailed Tahbou’s use of

old cracked wood to give his sculptures the illusion of age.

34. The context of the composition of royal treasuries in the

Grassfi elds was fi rst investigated by Christraud Geary in

Things of the Palace: A Catalogue of the Bamum Palace

Museum in Foumban (Cameroon), Wiesbaden: Franz

Steiner Verlag, 1983; then Jean-Paul Notué was responsible

for a series of publications on Bamileke royal treasuries

turned into museums including Bandjoun, Baham, Mankon,

and Babungo. Recently the contemporary role of these

Bamileke royal treasuries as “lending museums” was

considered in Erica P. Jones, “A Lending Museum. The

Movement of Objects and the Impact of the Museum

Space in the Grassfi elds (Cameroon),” African Arts, Summer

2016, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 14–27.

35. Notué and Triaca 2005.

36. Following the concept as defi ned by sociologists E. J.

Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (eds.) in The Invention of

Tradition, 1983, Cambridge University Press.

37. Dominique Malaquais in African Art from the Menil

Collection, Kristina Van Dyke (ed.), Houston: The Menil

Collection, 2008, and further in Dominique Malaquais,

Architecture, pouvoir et dissidence au Cameroun. Paris:

Karthala, Yaoundé, Cameroon: Presses de l’UCAC, 2002.

38. Forni 2016.

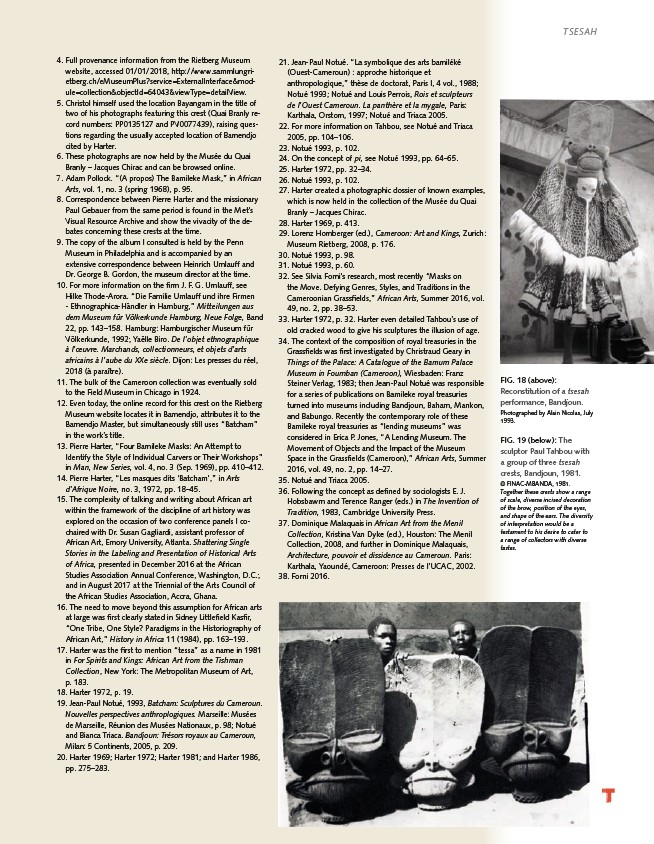

FIG. 18 (above):

Reconstitution of a tsesah

performance, Bandjoun.

Photographed by Alain Nicolas, July

1993.

FIG. 19 (below): The

sculptor Paul Tahbou with

a group of three tsesah

crests, Bandjoun, 1981.

© FINAC-MBANDA, 1981.

Together these crests show a range

of scale, diverse incised decoration

of the brow, position of the eyes,

and shape of the ears. The diversity

of interpretation would be a

testament to his desire to cater to

a range of collectors with diverse

tastes.

4. Full provenance information from the Rietberg Museum

website, accessed 01/01/2018, http://www.sammlungrietberg.

ch/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=

collection&objectId=64043&viewType=detailView.

5. Christol himself used the location Bayangam in the title of

two of his photographs featuring this crest (Quai Branly record

numbers: PP0135127 and PV0077439), raising questions

regarding the usually accepted location of Bamendjo

cited by Harter.

6. These photographs are now held by the Musée du Quai

Branly – Jacques Chirac and can be browsed online.

7. Adam Pollock. “(A propos) The Bamileke Mask,” in African

Arts, vol. 1, no. 3 (spring 1968), p. 95.

8. Correspondence between Pierre Harter and the missionary

Paul Gebauer from the same period is found in the Met’s

Visual Resource Archive and show the vivacity of the debates

concerning these crests at the time.

9. The copy of the album I consulted is held by the Penn

Museum in Philadelphia and is accompanied by an

extensive correspondence between Heinrich Umlauff and

Dr. George B. Gordon, the museum director at the time.

10. For more information on the fi rm J. F. G. Umlauff, see

Hilke Thode-Arora. “Die Familie Umlauff und ihre Firmen

- Ethnographica-Händler in Hamburg,” Mitteilungen aus

dem Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg, Neue Folge, Band

22, pp. 143–158. Hamburg: Hamburgischer Museum für

Völkerkunde, 1992; Yaëlle Biro. De l’objet ethnographique

à l’oeuvre. Marchands, collectionneurs, et objets d’arts

africains à l’aube du XXe siècle. Dijon: Les presses du réel,

2018 (à paraître).

11. The bulk of the Cameroon collection was eventually sold

to the Field Museum in Chicago in 1924.

12. Even today, the online record for this crest on the Rietberg

Museum website locates it in Bamendjo, attributes it to the

Bamendjo Master, but simultaneously still uses “Batcham”

in the work’s title.

13. Pierre Harter, “Four Bamileke Masks: An Attempt to

Identify the Style of Individual Carvers or Their Workshops”

in Man, New Series, vol. 4, no. 3 (Sep. 1969), pp. 410–412.

14. Pierre Harter, “Les masques dits ‘Batcham’,” in Arts

d’Afrique Noire, no. 3, 1972, pp. 18–45.

15. The complexity of talking and writing about African art

within the framework of the discipline of art history was

explored on the occasion of two conference panels I cochaired

with Dr. Susan Gagliardi, assistant professor of

African Art, Emory University, Atlanta. Shattering Single

Stories in the Labeling and Presentation of Historical Arts

of Africa, presented in December 2016 at the African

Studies Association Annual Conference, Washington, D.C.;

and in August 2017 at the Triennial of the Arts Council of

the African Studies Association, Accra, Ghana.

16. The need to move beyond this assumption for African arts

at large was fi rst clearly stated in Sidney Littlefi eld Kasfi r,

“One Tribe, One Style? Paradigms in the Historiography of

African Art,” History in Africa 11 (1984), pp. 163–193.

17. Harter was the fi rst to mention “tessa” as a name in 1981

in For Spirits and Kings: African Art from the Tishman

Collection, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

p. 183.

18. Harter 1972, p. 19.

19. Jean-Paul Notué, 1993, Batcham: Sculptures du Cameroun.

Nouvelles perspectives anthroplogiques. Marseille: Musées

de Marseille, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, p. 98; Notué

and Bianca Triaca. Bandjoun: Trésors royaux au Cameroun,

Milan: 5 Continents, 2005, p. 209.

20. Harter 1969; Harter 1972; Harter 1981; and Harter 1986,

pp. 275–283.