82

FIG. 10 (below left):

Codex Ixtlilxochitl, Folio 106, depicting

the Tetzcocan ruler Nezahualcoyotl

(Fasting Coyote, 1402–1472), compiled

by Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl (Nahua–

Spanish, c. AD 1578–1650).

Folio 106: Tetzcoco, Mexico. AD 1582.

Paper, pigment. Closed: 31 x 21 cm.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, inv. Ms. Mex.

65-71.

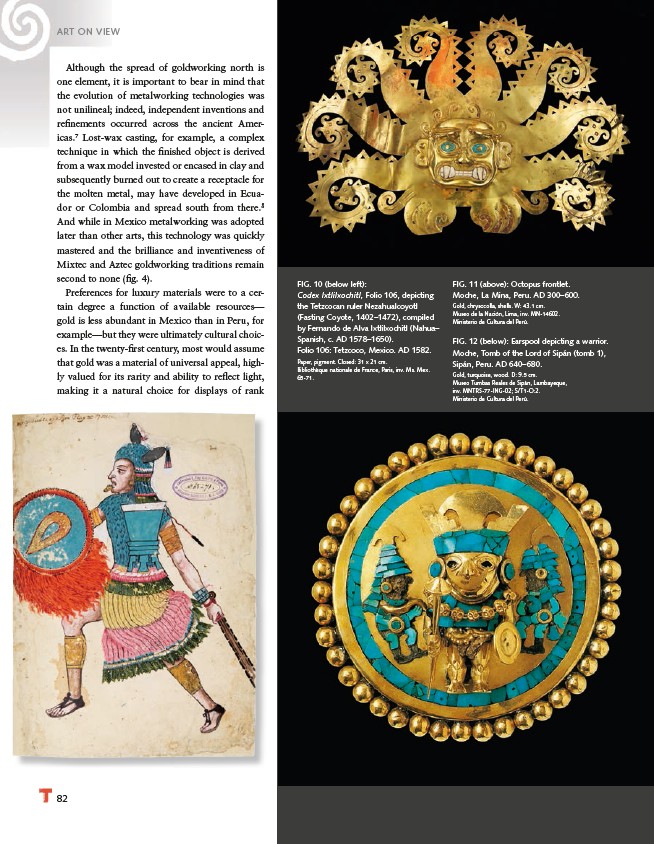

FIG. 11 (above): Octopus frontlet.

Moche, La Mina, Peru. AD 300–600.

Gold, chrysocolla, shells. W: 43.1 cm.

Museo de la Nación, Lima, inv. MN-14602.

Ministerio de Cultura del Perú.

FIG. 12 (below): Earspool depicting a warrior.

Moche, Tomb of the Lord of Sipán (tomb 1),

Sipán, Peru. AD 640–680.

Gold, turquoise, wood. D: 9.5 cm.

Museo Tumbas Reales de Sipán, Lambayeque,

inv. MNTRS-77-ING-02; S/T1-O:2.

Ministerio de Cultura del Perú.

ART ON VIEW

Although the spread of goldworking north is

one element, it is important to bear in mind that

the evolution of metalworking technologies was

not unilineal; indeed, independent inventions and

refi nements occurred across the ancient Americas.

7 Lost-wax casting, for example, a complex

technique in which the fi nished object is derived

from a wax model invested or encased in clay and

subsequently burned out to create a receptacle for

the molten metal, may have developed in Ecuador

or Colombia and spread south from there.8

And while in Mexico metalworking was adopted

later than other arts, this technology was quickly

mastered and the brilliance and inventiveness of

Mixtec and Aztec goldworking traditions remain

second to none (fi g. 4).

Preferences for luxury materials were to a certain

degree a function of available resources—

gold is less abundant in Mexico than in Peru, for

example—but they were ultimately cultural choices.

In the twenty-fi rst century, most would assume

that gold was a material of universal appeal, highly

valued for its rarity and ability to refl ect light,

making it a natural choice for displays of rank