159

most part trained at academies and entrenched in

the mainstream of the fi gurative and allegorical

trends of European artistic tradition.

Names such as Géo Michel and Jeanne Thil,

whose works are presented in Peintures des

Lointains, illustrate this. Canvases commissioned

from the latter in 1935 for the decoration of the

Palais de la France d’Outre-Mer at the Universal

Exposition in Brussels depict scenes of indigenous

peoples inhabiting French territories,

especially Equatorial and West Africa (fi g. 6),

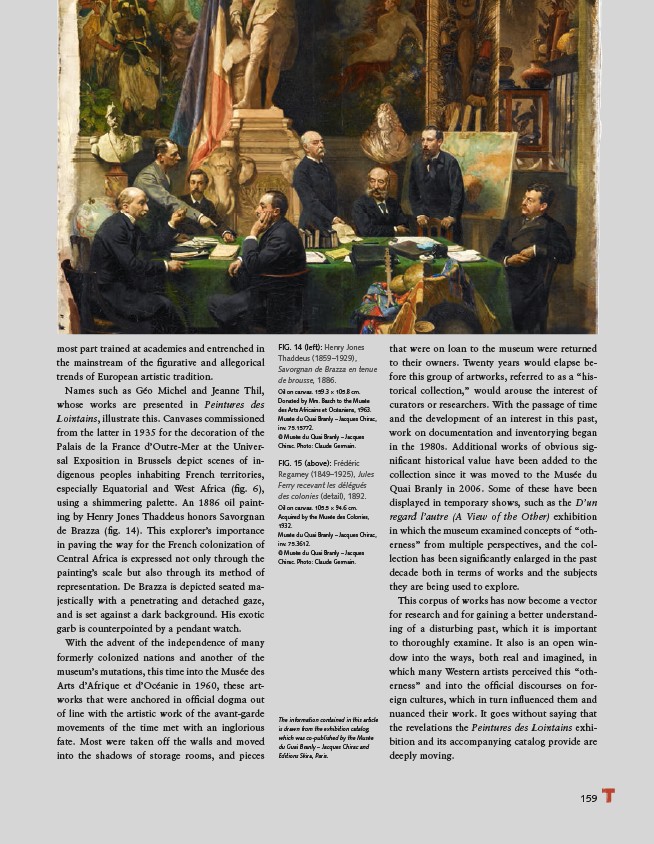

using a shimmering palette. An 1886 oil painting

by Henry Jones Thaddeus honors Savorgnan

de Brazza (fi g. 14). This explorer’s importance

in paving the way for the French colonization of

Central Africa is expressed not only through the

painting’s scale but also through its method of

representation. De Brazza is depicted seated majestically

with a penetrating and detached gaze,

and is set against a dark background. His exotic

garb is counterpointed by a pendant watch.

With the advent of the independence of many

formerly colonized nations and another of the

museum’s mutations, this time into the Musée des

Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie in 1960, these artworks

that were anchored in offi cial dogma out

of line with the artistic work of the avant-garde

movements of the time met with an inglorious

fate. Most were taken off the walls and moved

into the shadows of storage rooms, and pieces

FIG. 14 (left): Henry Jones

Thaddeus (1859–1929),

Savorgnan de Brazza en tenue

de brousse, 1886.

Oil on canvas. 159.3 × 105.8 cm.

Donated by Mrs. Basch to the Musée

des Arts Africains et Océaniens, 1963.

Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac,

inv. 75.15772.

© Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques

Chirac. Photo: Claude Germain.

FIG. 15 (above): Frédéric

Regamey (1849–1925), Jules

Ferry recevant les délégués

des colonies (detail), 1892.

Oil on canvas. 105.5 × 94.6 cm.

Acquired by the Musée des Colonies,

1932.

Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac,

inv. 75.3612.

© Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques

Chirac. Photo: Claude Germain.

The information contained in this article

is drawn from the exhibition catalog,

which was co-published by the Musée

du Guai Branly – Jacques Chirac and

Editions Skira, Paris.

that were on loan to the museum were returned

to their owners. Twenty years would elapse before

this group of artworks, referred to as a “historical

collection,” would arouse the interest of

curators or researchers. With the passage of time

and the development of an interest in this past,

work on documentation and inventorying began

in the 1980s. Additional works of obvious signifi

cant historical value have been added to the

collection since it was moved to the Musée du

Quai Branly in 2006. Some of these have been

displayed in temporary shows, such as the D’un

regard l’autre (A View of the Other) exhibition

in which the museum examined concepts of “otherness”

from multiple perspectives, and the collection

has been signifi cantly enlarged in the past

decade both in terms of works and the subjects

they are being used to explore.

This corpus of works has now become a vector

for research and for gaining a better understanding

of a disturbing past, which it is important

to thoroughly examine. It also is an open window

into the ways, both real and imagined, in

which many Western artists perceived this “otherness”

and into the offi cial discourses on foreign

cultures, which in turn infl uenced them and

nuanced their work. It goes without saying that

the revelations the Peintures des Lointains exhibition

and its accompanying catalog provide are

deeply moving.