97

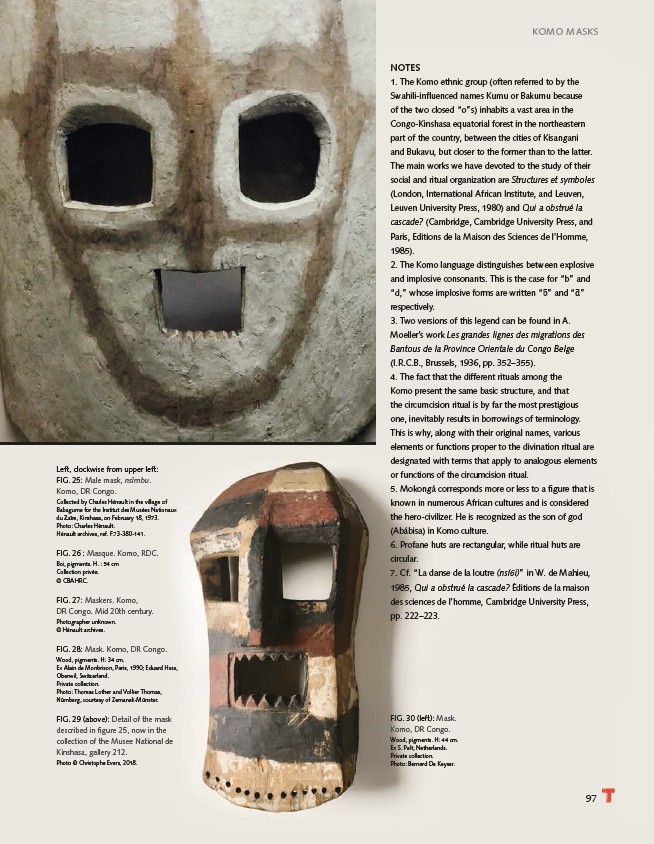

FIG. 30 (left): Mask.

Komo, DR Congo.

Wood, pigments. H: 44 cm.

Ex S. Pelt, Netherlands.

Private collection.

Photo: Bernard De Keyser.

KOMO MASKS

NOTES

1. The Komo ethnic group (often referred to by the

Swahili-influenced names Kumu or Bakumu because

of the two closed “o”s) inhabits a vast area in the

Congo-Kinshasa equatorial forest in the northeastern

part of the country, between the cities of Kisangani

and Bukavu, but closer to the former than to the latter.

The main works we have devoted to the study of their

social and ritual organization are Structures et symboles

(London, International African Institute, and Leuven,

Leuven University Press, 1980) and Qui a obstrué la

cascade? (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, and

Paris, Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme,

1985).

2. The Komo language distinguishes between explosive

and implosive consonants. This is the case for “b” and

“d,” whose implosive forms are written “ƃ” and “ƌ”

respectively.

3. Two versions of this legend can be found in A.

Moeller’s work Les grandes lignes des migrations des

Bantous de la Province Orientale du Congo Belge

(I.R.C.B., Brussels, 1936, pp. 352–355).

4. The fact that the different rituals among the

Komo present the same basic structure, and that

the circumcision ritual is by far the most prestigious

one, inevitably results in borrowings of terminology.

This is why, along with their original names, various

elements or functions proper to the divination ritual are

designated with terms that apply to analogous elements

or functions of the circumcision ritual.

5. Mokongá corresponds more or less to a figure that is

known in numerous African cultures and is considered

the hero-civilizer. He is recognized as the son of god

(Abábisa) in Komo culture.

6. Profane huts are rectangular, while ritual huts are

circular.

7. Cf. “La danse de la loutre (nsíбi)” in W. de Mahieu,

1985, Qui a obstrué la cascade? Éditions de la maison

des sciences de l’homme, Cambridge University Press,

pp. 222–223.

Left, clockwise from upper left:

FIG. 25: Male mask, nsîmbu.

Komo, DR Congo.

Collected by Charles Hénault in the village of

Babagume for the Institut des Musées Nationaux

du Zaïre, Kinshasa, on February 18, 1973.

Photo: Charles Hénault.

Hénault archives, ref. F.73-380-141.

FIG. 26 : Masque. Komo, RDC.

Boi, pigments. H. : 54 cm

Collection privée.

© CBAHRC.

FIG. 27: Maskers. Komo,

DR Congo. Mid 20th century.

Photographer unknown.

© Hénault archives.

FIG. 28: Mask. Komo, DR Congo.

Wood, pigments. H: 34 cm.

Ex Alain de Monbrison, Paris, 1990; Eduard Hess,

Oberwil, Switzerland.

Private collection.

Photo: Thomas Lother and Volker Thomas,

Nürnberg, courtesy of Zemanek-Münster.

FIG. 29 (above): Detail of the mask

described in figure 25, now in the

collection of the Musee National de

Kinshasa, gallery 212.

Photo © Christophe Evers, 2018.