73

RELIGIONS OF ECSTASY

sacrifice. This sacrifice is acknowledged by all

the Abrahamic religions, and it also serves as a

reminder that sacrifice in African religions serves a

comparable purpose. There is an important lesson

of parallelism to be learned here.

The exhibition continues with an examination

of the cults of possession. Particular emphasis is

placed on Beninese Vodun, most notably evoked

by a selection of bochio figures (fig. 9), a series

of small figurines created in the 1920s by Yesufu

Asogba (who died around 1930), and a group

of axes, or recades, that illustrate the connection

between political power and religion, since Vodun

served as a tool for the sacralization of power in

Abomey.

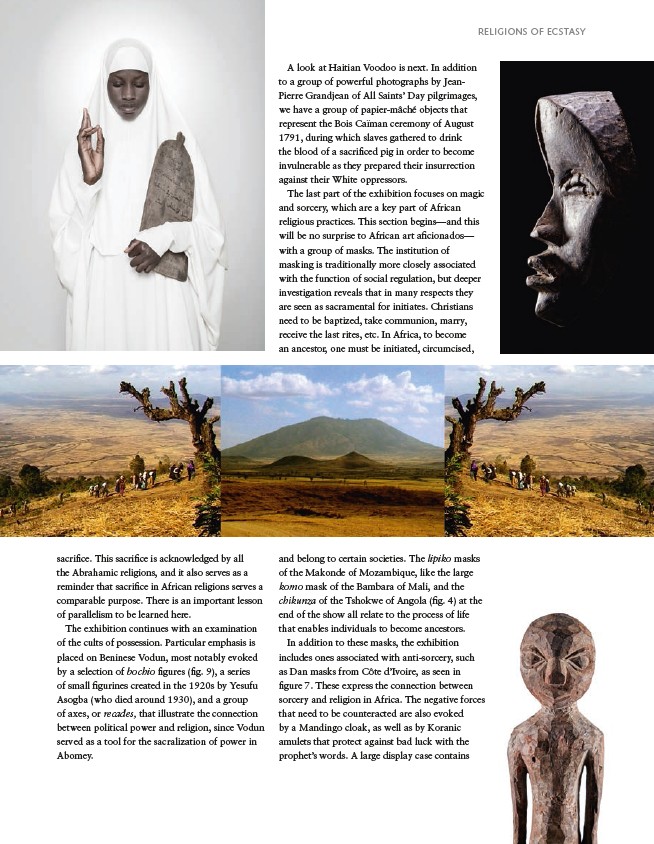

A look at Haitian Voodoo is next. In addition

to a group of powerful photographs by Jean-

Pierre Grandjean of All Saints’ Day pilgrimages,

we have a group of papier-mâché objects that

represent the Bois Caïman ceremony of August

1791, during which slaves gathered to drink

the blood of a sacrificed pig in order to become

invulnerable as they prepared their insurrection

against their White oppressors.

The last part of the exhibition focuses on magic

and sorcery, which are a key part of African

religious practices. This section begins—and this

will be no surprise to African art aficionados—

with a group of masks. The institution of

masking is traditionally more closely associated

with the function of social regulation, but deeper

investigation reveals that in many respects they

are seen as sacramental for initiates. Christians

need to be baptized, take communion, marry,

receive the last rites, etc. In Africa, to become

an ancestor, one must be initiated, circumcised,

and belong to certain societies. The lipiko masks

of the Makonde of Mozambique, like the large

komo mask of the Bambara of Mali, and the

chikunza of the Tshokwe of Angola (fig. 4) at the

end of the show all relate to the process of life

that enables individuals to become ancestors.

In addition to these masks, the exhibition

includes ones associated with anti-sorcery, such

as Dan masks from Côte d’Ivoire, as seen in

figure 7. These express the connection between

sorcery and religion in Africa. The negative forces

that need to be counteracted are also evoked

by a Mandingo cloak, as well as by Koranic

amulets that protect against bad luck with the

prophet’s words. A large display case contains