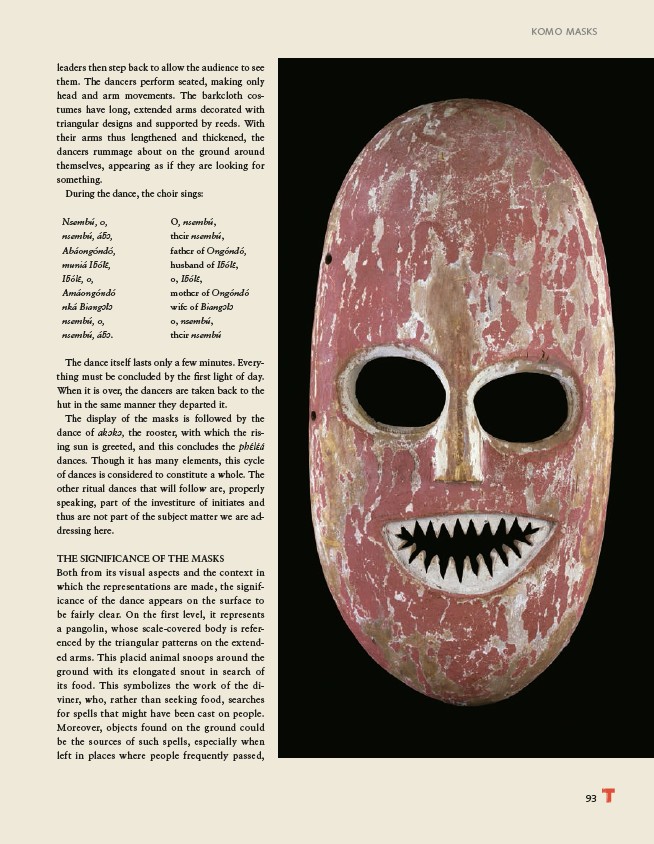

KOMO MASKS

93

leaders then step back to allow the audience to see

them. The dancers perform seated, making only

head and arm movements. The barkcloth costumes

have long, extended arms decorated with

triangular designs and supported by reeds. With

their arms thus lengthened and thickened, the

dancers rummage about on the ground around

themselves, appearing as if they are looking for

something.

During the dance, the choir sings:

Nsembú, o, O, nsembú,

nsembú, áƃɔ, their nsembú,

Abáongóndó, father of Ongóndó,

muniá Iƃólέ, husband of Iƃólέ,

Iƃólέ, o, o, Iƃólέ,

Amáongóndó mother of Ongóndó

nká Biangɔlɔ wife of Biangɔlɔ

nsembú, o, o, nsembú,

nsembú, áƃɔ. their nsembú

The dance itself lasts only a few minutes. Everything

must be concluded by the first light of day.

When it is over, the dancers are taken back to the

hut in the same manner they departed it.

The display of the masks is followed by the

dance of akɔkɔ, the rooster, with which the rising

sun is greeted, and this concludes the phέlέá

dances. Though it has many elements, this cycle

of dances is considered to constitute a whole. The

other ritual dances that will follow are, properly

speaking, part of the investiture of initiates and

thus are not part of the subject matter we are addressing

here.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE MASKS

Both from its visual aspects and the context in

which the representations are made, the significance

of the dance appears on the surface to

be fairly clear. On the first level, it represents

a pangolin, whose scale-covered body is referenced

by the triangular patterns on the extended

arms. This placid animal snoops around the

ground with its elongated snout in search of

its food. This symbolizes the work of the diviner,

who, rather than seeking food, searches

for spells that might have been cast on people.

Moreover, objects found on the ground could

be the sources of such spells, especially when

left in places where people frequently passed,