79

mountains, sweeping horizons, and mirages that

shimmer above the cracked earth (fig. 4). Close

inspection of the bowls reveals surprising details:

Scenes painted on concave surfaces appear flat

and figures merge and flow between foreground

and background, resulting in Escheresque impossibilities

in design (fig. 5).6 The Mimbres

bowls on view at the de Young demonstrate the

perception, imagination, and sophistication of

their ancient makers.

Arranged in an intimate side gallery (fig. 9),

Native Artists of Western North America includes

a selection of stunning masterworks made

by Navajo (Diné) weavers.7 The eight textiles on

view demonstrate the classic forms of Navajo

weavings: the elegantly minimalist chief blanket

and the dazzlingly ornate serape. Chief blankets

were woven on a horizontal plane and were

worn wrapped around the body, following the

model of the large, white textiles made by their

Pueblo neighbors.8 The earliest examples feature

thick stripes of creams, browns, and blues

(fig. 6). Weavers then elaborated the banded design,

adding bold red punctuations of rectangles

and later stepped-triangle and diamond motifs.

The serape tradition developed concurrently.

Navajo weavers were inspired by the intricate

Saltillo serapes that were au courant in Mexican

men’s fashion. They extracted the serrated-diamond

motif from the dizzying Saltillo serapes,

weaving elaborate geometric designs on crimson

backgrounds according to their own principles

of symmetry and balance (fig. 7). Distinguished

by their refined aesthetics and exceptional quality,

Navajo blankets are considered among the

finest textiles from the American Southwest.9

The textiles on view were all woven during the

mid to late nineteenth century, a period marked

by intense colonial expansion across the West.

In 1863, the U.S. government forced thousands

of Navajo from their land and made them relocate

to the Bosque Redondo reservation, where

they remained interned for five years. During

this time, weavers had limited access to their

own materials and began to use the commercially

spun and synthetically dyed yarns that were

issued by the U.S. government.10 Despite adversity,

weavers elaborated their practice, experimenting

with a new spectrum of bright colors

to enhance their designs (fig. 8). This artistic in-

FIG. 4 (facing page top):

Bowl with deer and geometric

landscape.

Mimbres artist, New Mexico,

United States. C. 1000–1150.

Earthenware, pigment. D: 27 cm.

Gift of the Thomas W. Weisel Family to

the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco,

inv. 2013.76.168.

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums

of San Francisco.

FIG. 5 (facing page bottom):

Bowl with human-avian figure.

Mimbres artist, New Mexico,

United States. C. 1000–1150.

Earthenware, pigment. D: 24.7 cm.

Gift of the Thomas W. Weisel Family to

the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco,

inv. 2013.76.99.

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums

of San Francisco.

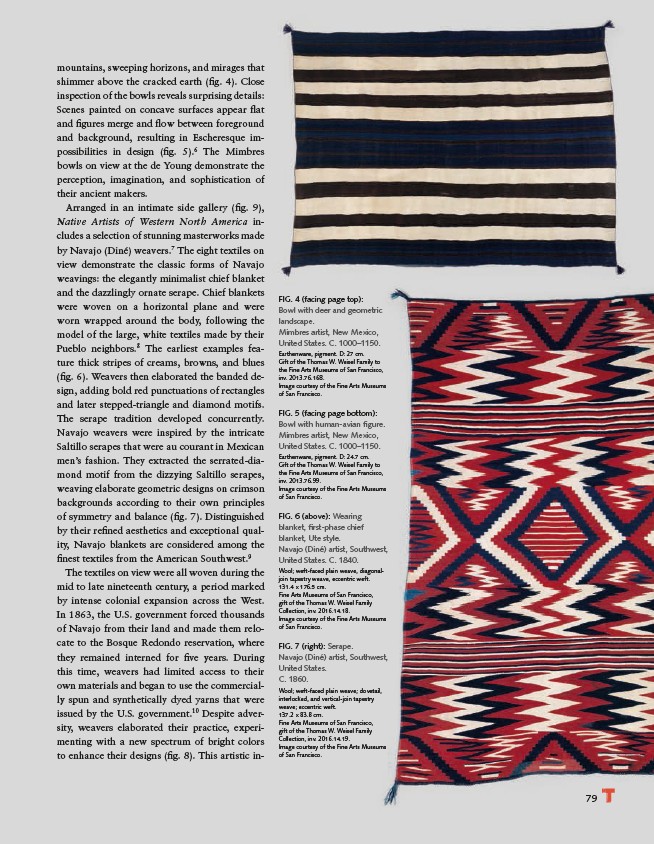

FIG. 6 (above): Wearing

blanket, first-phase chief

blanket, Ute style.

Navajo (Diné) artist, Southwest,

United States. C. 1840.

Wool; weft-faced plain weave, diagonaljoin

tapestry weave, eccentric weft.

131.4 x 176.5 cm.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco,

gift of the Thomas W. Weisel Family

Collection, inv. 2016.14.18.

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums

of San Francisco.

FIG. 7 (right): Serape.

Navajo (Diné) artist, Southwest,

United States.

C. 1860.

Wool; weft-faced plain weave; dovetail,

interlocked, and vertical-join tapestry

weave; eccentric weft.

137.2 x 83.8 cm.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco,

gift of the Thomas W. Weisel Family

Collection, inv. 2016.14.19.

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums

of San Francisco.