2

Editorial

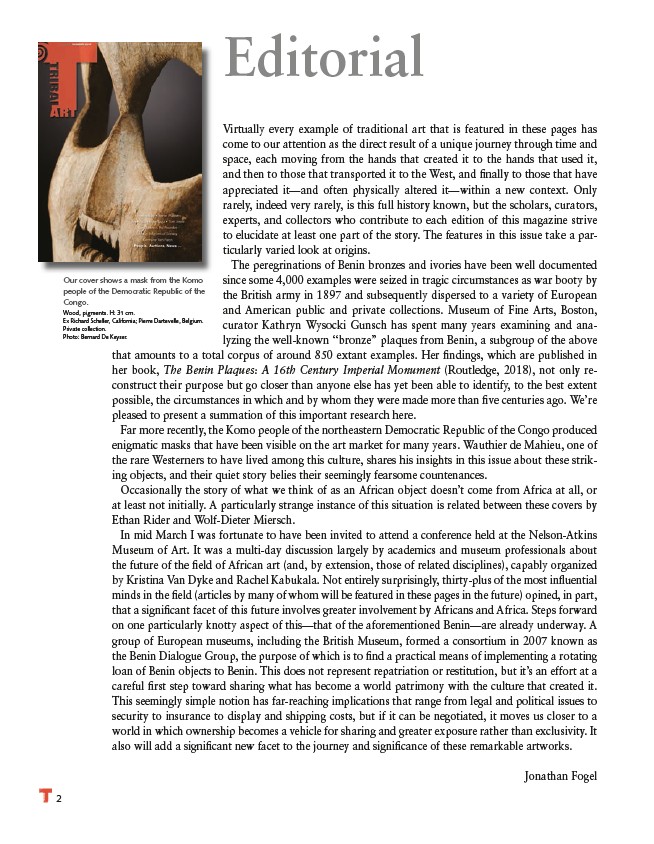

Our cover shows a mask from the Komo

people of the Democratic Republic of the

Congo.

Wood, pigments. H: 31 cm.

Ex Richard Scheller, California; Pierre Dartevelle, Belgium.

Private collection.

Photo: Bernard De Keyser.

Virtually every example of traditional art that is featured in these pages has

come to our attention as the direct result of a unique journey through time and

space, each moving from the hands that created it to the hands that used it,

and then to those that transported it to the West, and fi nally to those that have

appreciated it—and often physically altered it—within a new context. Only

rarely, indeed very rarely, is this full history known, but the scholars, curators,

experts, and collectors who contribute to each edition of this magazine strive

to elucidate at least one part of the story. The features in this issue take a particularly

varied look at origins.

The peregrinations of Benin bronzes and ivories have been well documented

since some 4,000 examples were seized in tragic circumstances as war booty by

the British army in 1897 and subsequently dispersed to a variety of European

and American public and private collections. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,

curator Kathryn Wysocki Gunsch has spent many years examining and analyzing

the well-known “bronze” plaques from Benin, a subgroup of the above

that amounts to a total corpus of around 850 extant examples. Her fi ndings, which are published in

her book, The Benin Plaques: A 16th Century Imperial Monument (Routledge, 2018), not only reconstruct

their purpose but go closer than anyone else has yet been able to identify, to the best extent

possible, the circumstances in which and by whom they were made more than fi ve centuries ago. We’re

pleased to present a summation of this important research here.

Far more recently, the Komo people of the northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo produced

enigmatic masks that have been visible on the art market for many years. Wauthier de Mahieu, one of

the rare Westerners to have lived among this culture, shares his insights in this issue about these striking

objects, and their quiet story belies their seemingly fearsome countenances.

Occasionally the story of what we think of as an African object doesn’t come from Africa at all, or

at least not initially. A particularly strange instance of this situation is related between these covers by

Ethan Rider and Wolf-Dieter Miersch.

In mid March I was fortunate to have been invited to attend a conference held at the Nelson-Atkins

Museum of Art. It was a multi-day discussion largely by academics and museum professionals about

the future of the fi eld of African art (and, by extension, those of related disciplines), capably organized

by Kristina Van Dyke and Rachel Kabukala. Not entirely surprisingly, thirty-plus of the most infl uential

minds in the fi eld (articles by many of whom will be featured in these pages in the future) opined, in part,

that a signifi cant facet of this future involves greater involvement by Africans and Africa. Steps forward

on one particularly knotty aspect of this—that of the aforementioned Benin—are already underway. A

group of European museums, including the British Museum, formed a consortium in 2007 known as

the Benin Dialogue Group, the purpose of which is to fi nd a practical means of implementing a rotating

loan of Benin objects to Benin. This does not represent repatriation or restitution, but it’s an effort at a

careful fi rst step toward sharing what has become a world patrimony with the culture that created it.

This seemingly simple notion has far-reaching implications that range from legal and political issues to

security to insurance to display and shipping costs, but if it can be negotiated, it moves us closer to a

world in which ownership becomes a vehicle for sharing and greater exposure rather than exclusivity. It

also will add a signifi cant new facet to the journey and signifi cance of these remarkable artworks.

Jonathan Fogel