32

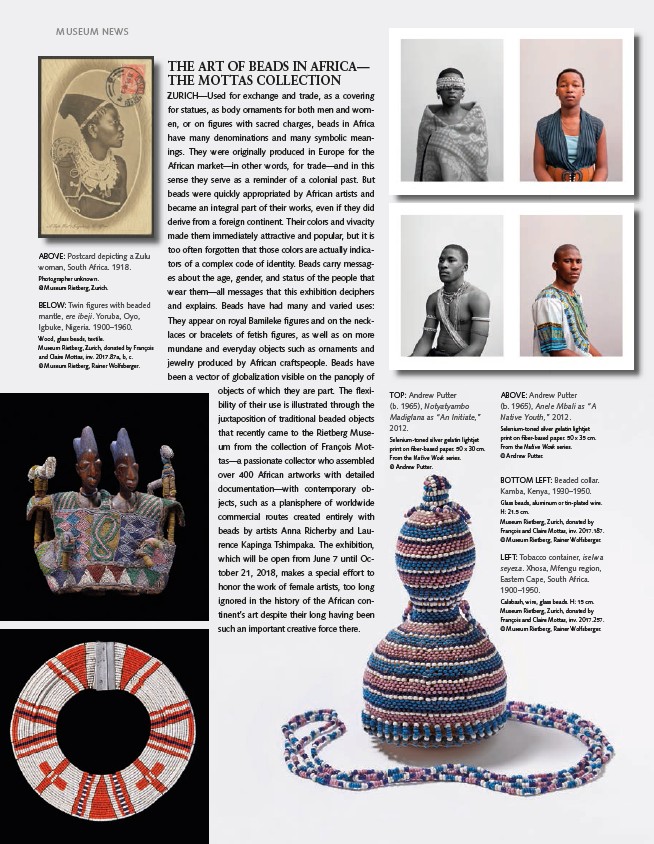

BOTTOM LEFT: Beaded collar.

Kamba, Kenya, 1930–1950.

Glass beads, aluminum or tin-plated wire.

H: 21.5 cm.

Museum Rietberg, Zurich, donated by

François and Claire Mottas, inv. 2017.187.

© Museum Rietberg, Rainer Wolfsberger.

LEFT: Tobacco container, iselwa

seyeza. Xhosa, Mfengu region,

Eastern Cape, South Africa.

1900–1950.

Calabash, wire, glass beads. H: 15 cm.

Museum Rietberg, Zurich, donated by

François and Claire Mottas, inv. 2017.257.

© Museum Rietberg, Rainer Wolfsberger.

ABOVE: Postcard depicting a Zulu

woman, South Africa. 1918.

Photographer unknown.

@ Museum Rietberg, Zurich.

BELOW: Twin fi gures with beaded

mantle, ere ibeji. Yoruba, Oyo,

Igbuke, Nigeria. 1900–1960.

Wood, glass beads, textile.

Museum Rietberg, Zurich, donated by François

and Claire Mottas, inv. 2017.87a, b, c.

© Museum Rietberg, Rainer Wolfsberger.

ABOVE: Andrew Putter

(b. 1965), Anele Mbali as “A

Native Youth,” 2012.

Selenium-toned silver gelatin lightjet

print on fi ber-based paper. 50 x 35 cm.

From the Native Work series.

© Andrew Putter.

TOP: Andrew Putter

(b. 1965), Notyatyambo

Madiglana as “An Initiate,”

2012.

Selenium-toned silver gelatin lightjet

print on fi ber-based paper. 50 x 30 cm.

From the Native Work series.

© Andrew Putter.

MUSEUM NEWS

THE ART OF BEADS IN AFRICA—

THE MOTTAS COLLECTION

ZURICH—Used for exchange and trade, as a covering

for statues, as body ornaments for both men and women,

or on fi gures with sacred charges, beads in Africa

have many denominations and many symbolic meanings.

They were originally produced in Europe for the

African market—in other words, for trade—and in this

sense they serve as a reminder of a colonial past. But

beads were quickly appropriated by African artists and

became an integral part of their works, even if they did

derive from a foreign continent. Their colors and vivacity

made them immediately attractive and popular, but it is

too often forgotten that those colors are actually indicators

of a complex code of identity. Beads carry messages

about the age, gender, and status of the people that

wear them—all messages that this exhibition deciphers

and explains. Beads have had many and varied uses:

They appear on royal Bamileke fi gures and on the necklaces

or bracelets of fetish fi gures, as well as on more

mundane and everyday objects such as ornaments and

jewelry produced by African craftspeople. Beads have

been a vector of globalization visible on the panoply of

objects of which they are part. The fl exibility

of their use is illustrated through the

juxtaposition of traditional beaded objects

that recently came to the Rietberg Museum

from the collection of François Mottas—

a passionate collector who assembled

over 400 African artworks with detailed

documentation—with contemporary objects,

such as a planisphere of worldwide

commercial routes created entirely with

beads by artists Anna Richerby and Laurence

Kapinga Tshimpaka. The exhibition,

which will be open from June 7 until October

21, 2018, makes a special effort to

honor the work of female artists, too long

ignored in the history of the African continent’s

art despite their long having been

such an important creative force there.