TRIBAL PEOPLE

K. C.: When did you start collecting African

art?

T. J.: Santa Fe has many ethnographic art dealers

and a fl ea market that was once international

in scope. In the early 1980s, people from

all over the world arrived with exceptional art

and artifacts for sale. The fi rst piece of African

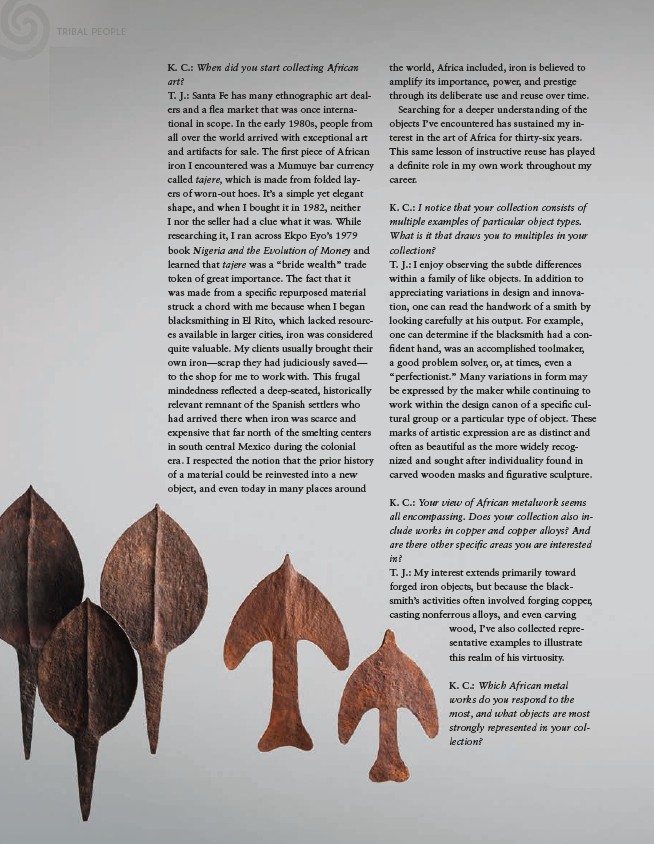

iron I encountered was a Mumuye bar currency

called tajere, which is made from folded layers

of worn-out hoes. It’s a simple yet elegant

shape, and when I bought it in 1982, neither

I nor the seller had a clue what it was. While

researching it, I ran across Ekpo Eyo’s 1979

book Nigeria and the Evolution of Money and

learned that tajere was a “bride wealth” trade

token of great importance. The fact that it

was made from a specifi c repurposed material

struck a chord with me because when I began

blacksmithing in El Rito, which lacked resources

available in larger cities, iron was considered

quite valuable. My clients usually brought their

own iron—scrap they had judiciously saved—

to the shop for me to work with. This frugal

mindedness refl ected a deep-seated, historically

relevant remnant of the Spanish settlers who

had arrived there when iron was scarce and

expensive that far north of the smelting centers

in south central Mexico during the colonial

era. I respected the notion that the prior history

of a material could be reinvested into a new

object, and even today in many places around

the world, Africa included, iron is believed to

amplify its importance, power, and prestige

through its deliberate use and reuse over time.

Searching for a deeper understanding of the

objects I’ve encountered has sustained my interest

in the art of Africa for thirty-six years.

This same lesson of instructive reuse has played

a defi nite role in my own work throughout my

career.

K. C.: I notice that your collection consists of

multiple examples of particular object types.

What is it that draws you to multiples in your

collection?

T. J.: I enjoy observing the subtle differences

within a family of like objects. In addition to

appreciating variations in design and innovation,

one can read the handwork of a smith by

looking carefully at his output. For example,

one can determine if the blacksmith had a confi

dent hand, was an accomplished toolmaker,

a good problem solver, or, at times, even a

“perfectionist.” Many variations in form may

be expressed by the maker while continuing to

work within the design canon of a specifi c cultural

group or a particular type of object. These

marks of artistic expression are as distinct and

often as beautiful as the more widely recognized

and sought after individuality found in

carved wooden masks and fi gurative sculpture.

K. C.: Your view of African metalwork seems

all encompassing. Does your collection also include

works in copper and copper alloys? And

are there other specifi c areas you are interested

in?

T. J.: My interest extends primarily toward

forged iron objects, but because the blacksmith’s

activities often involved forging copper,

casting nonferrous alloys, and even carving

wood, I’ve also collected representative

examples to illustrate

this realm of his virtuosity.

K. C.: Which African metal

works do you respond to the

most, and what objects are most

strongly represented in your collection?