ART ON VIEW

The installation opens with the monotheistic

Abrahamic religions: Christianity, Judaism, and

Islam. We start with a focus on the Ethiopian and

Eritrean Christian orthodox religion practiced

in the fourth century AD, and the artworks we

present in connection with it are an ensemble

of crosses, paintings, and liturgical objects. In

this Manichaean-leaning religion, the struggle

between good and evil is an everyday occurrence.

The presence of evil is revealed to the faithful,

particularly during periods of trance. Believers are

liberated by the touch of a Christian cross with

interlacing designs that evokes the eternal life to

come.

To illustrate the phenomenon of prophetism,

which is widespread in Africa, the exhibition

features a photograph of Jésus de Chingalala,

whom I met in 1997 when I was in the fi eld

doing my doctoral research in Zambezi, near

the Angolan border in Zambia’s Northwest

Province. Last year we found him in the same

place accompanied by his last two followers,

who happened also to be his two concubines.

His story and his perspective upon it enrich

the almost thirty interviews that the exhibition

presents. The fi rst section of the show concludes

with a refl ection on Judaism and Islam, primarily

through photography.

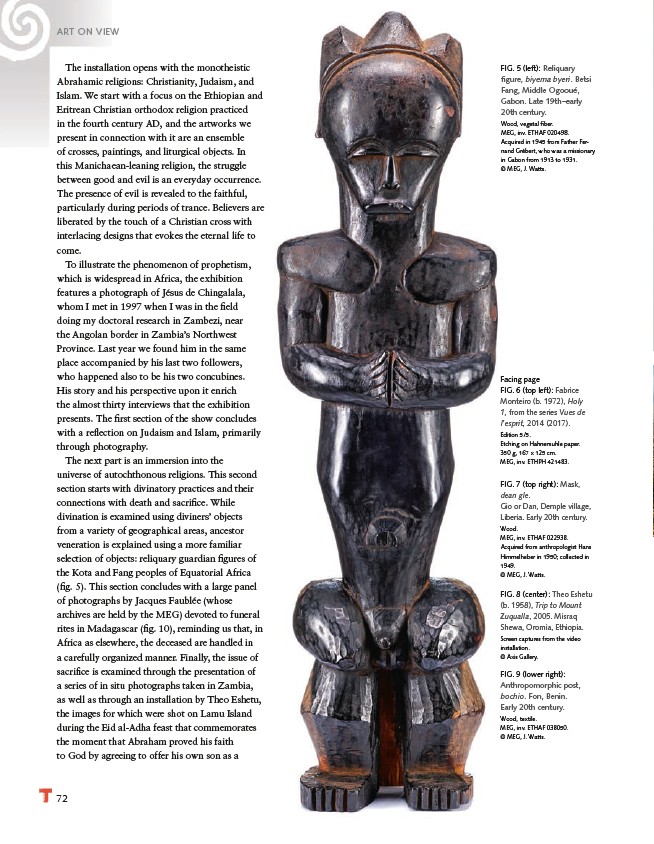

The next part is an immersion into the

universe of autochthonous religions. This second

section starts with divinatory practices and their

connections with death and sacrifi ce. While

divination is examined using diviners’ objects

from a variety of geographical areas, ancestor

veneration is explained using a more familiar

selection of objects: reliquary guardian fi gures of

the Kota and Fang peoples of Equatorial Africa

(fi g. 5). This section concludes with a large panel

of photographs by Jacques Faublée (whose

archives are held by the MEG) devoted to funeral

rites in Madagascar (fi g. 10), reminding us that, in

Africa as elsewhere, the deceased are handled in

a carefully organized manner. Finally, the issue of

sacrifi ce is examined through the presentation of

a series of in situ photographs taken in Zambia,

as well as through an installation by Theo Eshetu,

the images for which were shot on Lamu Island

during the Eid al-Adha feast that commemorates

the moment that Abraham proved his faith

to God by agreeing to offer his own son as a

72

FIG. 5 (left): Reliquary

fi gure, biyema byeri. Betsi

Fang, Middle Ogooué,

Gabon. Late 19th–early

20th century.

Wood, vegetal fi ber.

MEG, inv. ETHAF 020498.

Acquired in 1945 from Father Fernand

Grébert, who was a missionary

in Gabon from 1913 to 1931.

© MEG, J. Watts.

Facing page

FIG. 6 (top left): Fabrice

Monteiro (b. 1972), Holy

1, from the series Vues de

l’esprit, 2014 (2017).

Édition 5/5.

Etching on Hahnemuhle paper.

350 g, 167 x 125 cm.

MEG, inv. ETHPH 421483.

FIG. 7 (top right): Mask,

dean gle.

Gio or Dan, Demple village,

Liberia. Early 20th century.

Wood.

MEG, inv. ETHAF 022938.

Acquired from anthropologist Hans

Himmelheber in 1950; collected in

1949.

© MEG, J. Watts.

FIG. 8 (center): Theo Eshetu

(b. 1958), Trip to Mount

Zuqualla, 2005. Misraq

Shewa, Oromia, Ethiopia.

Screen captures from the video

installation.

© Axis Gallery.

FIG. 9 (lower right):

Anthropomorphic post,

bochio. Fon, Benin.

Early 20th century.

Wood, textile.

MEG, inv. ETHAF 038050.

© MEG, J. Watts.