74

a beautiful group of minkisi, or power fi gures,

many of which have not been publicly shown

since the Medusa exhibition ten years ago. The

ambivalent fi gure of Mami Wata is shown in

a variety of ways, including a fi ne and brightly

colored mask collected by Himmelheber (fi g. 12).

Lastly, the importance of twins, which are seen as

connected with the divine, is emphasized through

the presentation of a Dogon twin altar from Mali

and a pair of Yoruba ibeji from Nigeria.

T.A.M.: Aren’t all of these religions susceptible to

outside infl uences?

B.W.: Yes. In sub-Saharan Africa, one is born,

one lives, and one dies in an inevitable religious

context. Religion is not just about embracing a

faith, it is a way of life in which multiple realities

coexist. Even if you are Christian or Muslim, you

are exposed to magic, sorcery, and spirits.

Franck Houndégla’s immersive presentation

makes the point of such absence or barriers

extremely well. This Beninese artist brings a

special sensitivity to this project since he is so

close to this universe, which he knows and loves.

The result is a relatively open exhibition space

that allows visitors to circulate freely, moving

from one reality to another just by shifting their

glance. Another contemporary artist, Theo

Eshetu’s installations all have a soundtrack, as do

several videos, and these sound sources scattered

throughout the exhibition intentionally distract

from overly focused perceptions of single objects.

We have attempted to present and stage

the complexity of the religious phenomena in

Africa and to show the more or less harmonious

cohabitation of diverse realities. We have also

tried to evoke the characteristically African

superimposition of the religious and the profane,

at least within certain contexts. In many

traditional African religions, particularly in rural

areas but in towns as well, religious events may

have major festivals. Theo Eshetu masterfully

expresses this in his Trip to Mount Zuqualla

video installation, in which great hubbub and

commotion occur both while a pilgrimage of

believers is underway and during states of trance.

This confusion of sounds may seem odd and

surprising to the Western visitor, who customarily

associates solemn surroundings with the practice

of worship.

T.A.M.: You mentioned Theo Eshetu, the

Ethiopian artist whose work has been seen

at major contemporary art events such as

Documenta in Kassel and Athens. As in most

of MEG’s recent temporary exhibitions,

photography, electronic media, and contemporary

art are prominently featured here. Is this

approach a “hallmark” of the museum’s

exhibitions?

B.W.: Yes, absolutely. But it’s not just some sort

of marketing strategy. It comes from a deep

conviction that as many perspectives as possible

are needed in order to explore subjects that

blend art, society, and culture. The success of an

exhibition like Amazonia (more than 100,000

visitors at the MEG and 210,000 in Montreal) is,

in my opinion, due to this multiplicity of voices.

In Africa: The Religions of Ecstasy, engaging

different types of vocabularies (especially

photography and video) was at least as

important to me as showing traditional cultural

objects that, even when displayed as well as

they can be, are silent and thus inadequate

for expressing the experience that using them

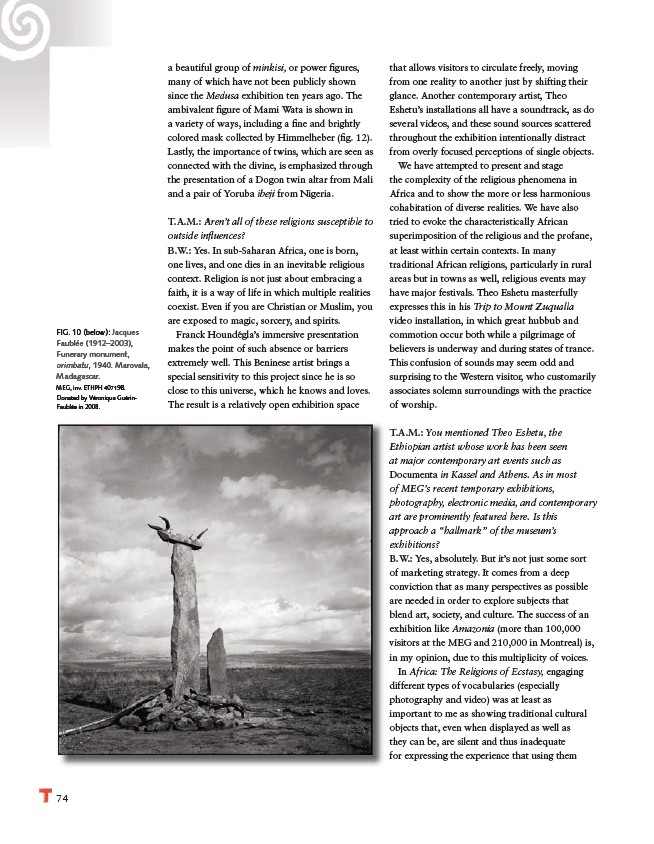

FIG. 10 (below): Jacques

Faublée (1912–2003),

Funerary monument,

orimbatu, 1940. Marovala,

Madagascar.

MEG, inv. ETHPH 407198.

Donated by Véronique Guérin-

Faublée in 2008.