K. C.: You’ve expanded the boundaries of

blacksmithing as an art form as evidenced by

the national and international awards and

recognitions you’ve received, but it’s far from

typical. How would you describe what you’re

doing?

T. J.: Even though I now make my living exclusively

134

as a sculptor, my origins as a blacksmith

provide the connective tissue toward thought

processes and solutions that are an inextricable

part of my practice as an artist. In fact, without

these skills, it would’ve been impossible

to have gained access to the state-of-the-art

industrial forging facility in Illinois where, for

the last fi fteen years, I’ve created the largescale

works, some pieces weighing in excess of

20,000 kilos. It’s precisely because we speak the

same fundamental language in this context that

I’m offered a seamless working environment

allowing hands-on orchestration as if I’m working

in my own studio, but with the aid of their

industrially scaled equipment.

Another advantage of producing my work

there is that it provides a means of keeping my

fi nger on the pulse of global political and economic

conditions driving this industry. They

furtively facilitate indispensable tasks that provide

a staggering array of goods and services that

human beings rely on. Blacksmiths have been

doing this for more than 3,000 years. They continue

to do so but are simply out of public view

now, performing with astonishing technological

innovations inside industrial facilities that are

closed to outsiders. By forging sculpture from

their massive remnants, literally hot-off-the-press

and acknowledging each piece as “offspring”

still metaphorically connected to its “parent”

material, I reference our dependency on forging

activities that remain at the cutting edge of our

lives. In every way imaginable, forged components

are churning away at the heart of energy

production, cultivation and processing of food,

extraction of mineral resources, protection of

borders, and even the exploration of our galaxy.

Our debt to these blacksmith/technicians and

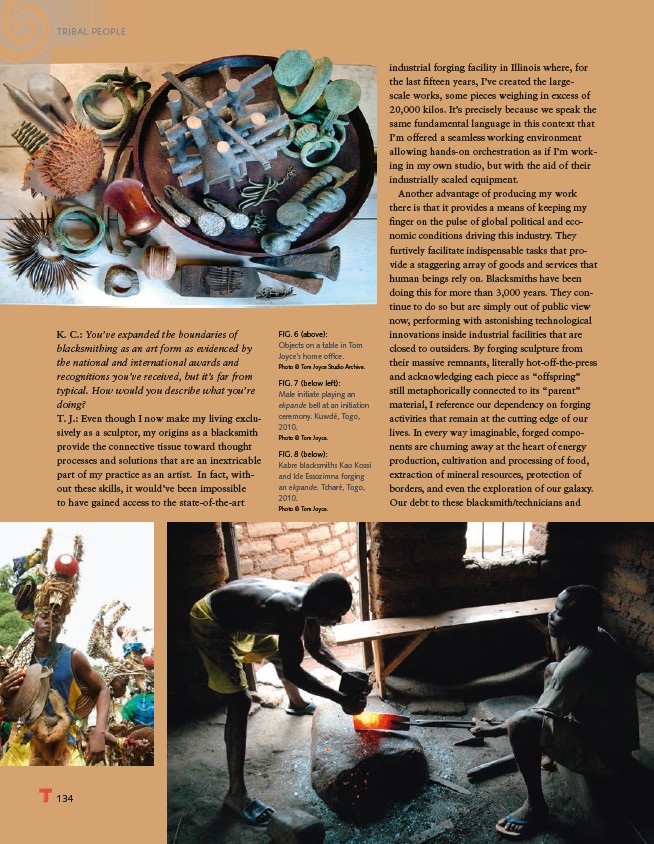

FIG. 6 (above):

Objects on a table in Tom

Joyce’s home offi ce.

Photo © Tom Joyce Studio Archive.

FIG. 7 (below left):

Male initiate playing an

ekpande bell at an initiation

ceremony. Kuwdé, Togo,

2010.

Photo © Tom Joyce.

FIG. 8 (below):

Kabre blacksmiths Kao Kossi

and Ide Essozimna forging

an ekpande. Tcharé, Togo,

2010.

Photo © Tom Joyce.

TRIBAL PEOPLE