BENIN PLAQUES

resent the first recorded account of the plaques’

history from members of the Benin court.

Roupell was an occupier and his account must

therefore be approached with some skepticism,

but it cannot be dismissed.

The sixteenth-century clothing on Portuguese

figures in the plaques provides a long-accepted

initial date for the plaques’ commission, but the

production timeline described above suggests

that the corpus was likely created in a shorter

time than previously supposed. The political

history of Benin in this period further corroborates

the oral history Roupell recorded. When

Esigie claimed the throne, his relationship with

his courtiers was seriously compromised due

to the war of succession that had placed him

there, the above-mentioned war with Idah (capital

of the Igala kingdom today), and the wars

of expansion led by his father, Ozolua (reigned

c. 1480s to 1516 or 1517). While he greatly

expanded the size and therefore the wealth

of the Benin kingdom, Ozolua’s never-ending

military campaign overtaxed the militias serving

the court, and his own warriors reportedly

killed him. Esigie inherited a divided court, an

army of weakened local militias, and a number

of newly conquered vassal states that had previously

revolted in an attempt to slip out from

under Benin’s control.

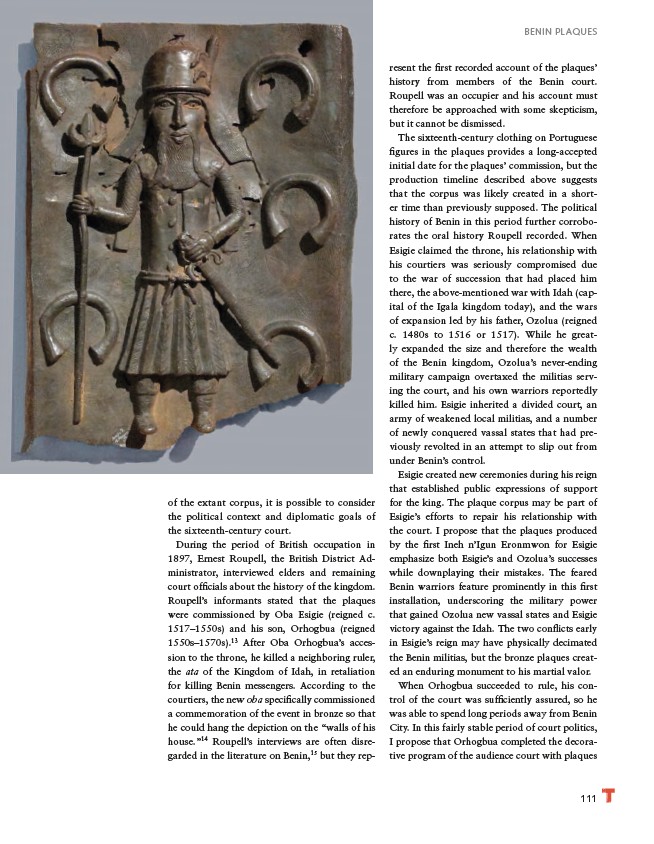

Esigie created new ceremonies during his reign

that established public expressions of support

for the king. The plaque corpus may be part of

Esigie’s efforts to repair his relationship with

the court. I propose that the plaques produced

by the first Ineh n’Igun Eronmwon for Esigie

emphasize both Esigie’s and Ozolua’s successes

while downplaying their mistakes. The feared

Benin warriors feature prominently in this first

installation, underscoring the military power

that gained Ozolua new vassal states and Esigie

victory against the Idah. The two conflicts early

in Esigie’s reign may have physically decimated

the Benin militias, but the bronze plaques created

an enduring monument to his martial valor.

When Orhogbua succeeded to rule, his control

of the court was sufficiently assured, so he

was able to spend long periods away from Benin

City. In this fairly stable period of court politics,

I propose that Orhogbua completed the decorative

program of the audience court with plaques

111

of the extant corpus, it is possible to consider

the political context and diplomatic goals of

the sixteenth-century court.

During the period of British occupation in

1897, Ernest Roupell, the British District Administrator,

interviewed elders and remaining

court officials about the history of the kingdom.

Roupell’s informants stated that the plaques

were commissioned by Oba Esigie (reigned c.

1517–1550s) and his son, Orhogbua (reigned

1550s–1570s).13 After Oba Orhogbua’s accession

to the throne, he killed a neighboring ruler,

the ata of the Kingdom of Idah, in retaliation

for killing Benin messengers. According to the

courtiers, the new oba specifically commissioned

a commemoration of the event in bronze so that

he could hang the depiction on the “walls of his

house.”14 Roupell’s interviews are often disregarded

in the literature on Benin,15 but they rep-