FEATURE

100

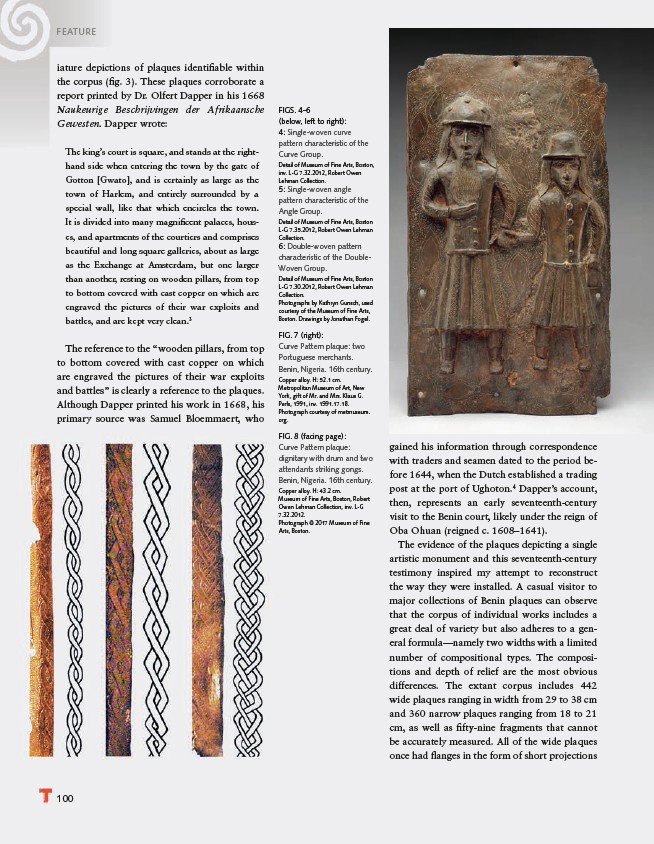

FIGS. 4–6

(below, left to right):

4: Single-woven curve

pattern characteristic of the

Curve Group.

Detail of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,

inv. L-G 7.32.2012, Robert Owen

Lehman Collection.

5: Single-woven angle

pattern characteristic of the

Angle Group.

Detail of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

L-G 7.35.2012, Robert Owen Lehman

Collection.

6: Double-woven pattern

characteristic of the Double-

Woven Group.

Detail of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

L-G 7.30.2012, Robert Owen Lehman

Collection.

Photographs by Kathryn Gunsch, used

courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston. Drawings by Jonathan Fogel.

FIG. 7 (right):

Curve Pattern plaque: two

Portuguese merchants.

Benin, Nigeria. 16th century.

Copper alloy. H: 52.1 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New

York, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Klaus G.

Perls, 1991, inv. 1991.17.18.

Photograph courtesy of metmuseum.

org.

FIG. 8 (facing page):

Curve Pattern plaque:

dignitary with drum and two

attendants striking gongs.

Benin, Nigeria. 16th century.

Copper alloy. H: 43.2 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Robert

Owen Lehman Collection, inv. L-G

7.32.2012.

Photograph © 2017 Museum of Fine

Arts, Boston.

iature depictions of plaques identifi able within

the corpus (fi g. 3). These plaques corroborate a

report printed by Dr. Olfert Dapper in his 1668

Naukeurige Beschrijvingen der Afrikaansche

Gewesten. Dapper wrote:

The king’s court is square, and stands at the righthand

side when entering the town by the gate of

Gotton Gwato, and is certainly as large as the

town of Harlem, and entirely surrounded by a

special wall, like that which encircles the town.

It is divided into many magnifi cent palaces, houses,

and apartments of the courtiers and comprises

beautiful and long square galleries, about as large

as the Exchange at Amsterdam, but one larger

than another, resting on wooden pillars, from top

to bottom covered with cast copper on which are

engraved the pictures of their war exploits and

battles, and are kept very clean.3

The reference to the “wooden pillars, from top

to bottom covered with cast copper on which

are engraved the pictures of their war exploits

and battles” is clearly a reference to the plaques.

Although Dapper printed his work in 1668, his

primary source was Samuel Bloemmaert, who

gained his information through correspondence

with traders and seamen dated to the period before

1644, when the Dutch established a trading

post at the port of Ughoton.4 Dapper’s account,

then, represents an early seventeenth-century

visit to the Benin court, likely under the reign of

Oba Ohuan (reigned c. 1608–1641).

The evidence of the plaques depicting a single

artistic monument and this seventeenth-century

testimony inspired my attempt to reconstruct

the way they were installed. A casual visitor to

major collections of Benin plaques can observe

that the corpus of individual works includes a

great deal of variety but also adheres to a general

formula—namely two widths with a limited

number of compositional types. The compositions

and depth of relief are the most obvious

differences. The extant corpus includes 442

wide plaques ranging in width from 29 to 38 cm

and 360 narrow plaques ranging from 18 to 21

cm, as well as fi fty-nine fragments that cannot

be accurately measured. All of the wide plaques

once had fl anges in the form of short projections