112

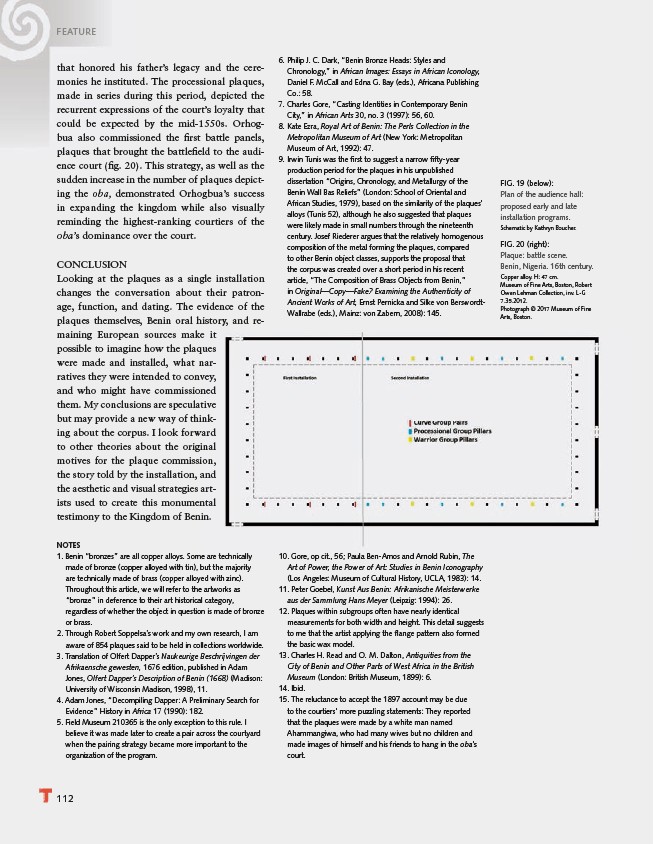

FIG. 19 (below):

Plan of the audience hall:

proposed early and late

installation programs.

Schematic by Kathryn Boucher.

FIG. 20 (right):

Plaque: battle scene.

Benin, Nigeria. 16th century.

Copper alloy. H: 47 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Robert

Owen Lehman Collection, inv. L-G

7.35.2012.

Photograph © 2017 Museum of Fine

Arts, Boston.

10. Gore, op cit., 56; Paula Ben-Amos and Arnold Rubin, The

Art of Power, the Power of Art: Studies in Benin Iconography

(Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, UCLA, 1983): 14.

11. Peter Goebel, Kunst Aus Benin: Afrikanische Meisterwerke

aus der Sammlung Hans Meyer (Leipzig: 1994): 26.

12. Plaques within subgroups often have nearly identical

measurements for both width and height. This detail suggests

to me that the artist applying the fl ange pattern also formed

the basic wax model.

13. Charles H. Read and O. M. Dalton, Antiquities from the

City of Benin and Other Parts of West Africa in the British

Museum (London: British Museum, 1899): 6.

14. Ibid.

15. The reluctance to accept the 1897 account may be due

to the courtiers’ more puzzling statements: They reported

that the plaques were made by a white man named

Ahammangiwa, who had many wives but no children and

made images of himself and his friends to hang in the oba’s

court.

FEATURE

that honored his father’s legacy and the ceremonies

he instituted. The processional plaques,

made in series during this period, depicted the

recurrent expressions of the court’s loyalty that

could be expected by the mid-1550s. Orhogbua

also commissioned the fi rst battle panels,

plaques that brought the battlefi eld to the audience

court (fi g. 20). This strategy, as well as the

sudden increase in the number of plaques depicting

the oba, demonstrated Orhogbua’s success

in expanding the kingdom while also visually

reminding the highest-ranking courtiers of the

oba’s dominance over the court.

CONCLUSION

Looking at the plaques as a single installation

changes the conversation about their patronage,

function, and dating. The evidence of the

plaques themselves, Benin oral history, and remaining

European sources make it

possible to imagine how the plaques

were made and installed, what narratives

they were intended to convey,

and who might have commissioned

them. My conclusions are speculative

but may provide a new way of thinking

about the corpus. I look forward

to other theories about the original

motives for the plaque commission,

the story told by the installation, and

the aesthetic and visual strategies artists

used to create this monumental

testimony to the Kingdom of Benin.

NOTES

1. Benin “bronzes” are all copper alloys. Some are technically

made of bronze (copper alloyed with tin), but the majority

are technically made of brass (copper alloyed with zinc).

Throughout this article, we will refer to the artworks as

“bronze” in deference to their art historical category,

regardless of whether the object in question is made of bronze

or brass.

2. Through Robert Soppelsa’s work and my own research, I am

aware of 854 plaques said to be held in collections worldwide.

3. Translation of Olfert Dapper’s Naukeurige Beschrijvingen der

Afrikaensche gewesten, 1676 edition, published in Adam

Jones, Olfert Dapper’s Description of Benin (1668) (Madison:

University of Wisconsin Madison, 1998), 11.

4. Adam Jones, “Decompiling Dapper: A Preliminary Search for

Evidence” History in Africa 17 (1990): 182.

5. Field Museum 210365 is the only exception to this rule. I

believe it was made later to create a pair across the courtyard

when the pairing strategy became more important to the

organization of the program.

6. Philip J. C. Dark, “Benin Bronze Heads: Styles and

Chronology,” in African Images: Essays in African Iconology,

Daniel F. McCall and Edna G. Bay (eds.), Africana Publishing

Co.: 58.

7. Charles Gore, “Casting Identities in Contemporary Benin

City,” in African Arts 30, no. 3 (1997): 56, 60.

8. Kate Ezra, Royal Art of Benin: The Perls Collection in the

Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan

Museum of Art, 1992): 47.

9. Irwin Tunis was the fi rst to suggest a narrow fi fty-year

production period for the plaques in his unpublished

dissertation “Origins, Chronology, and Metallurgy of the

Benin Wall Bas Reliefs” (London: School of Oriental and

African Studies, 1979), based on the similarity of the plaques’

alloys (Tunis 52), although he also suggested that plaques

were likely made in small numbers through the nineteenth

century. Josef Riederer argues that the relatively homogenous

composition of the metal forming the plaques, compared

to other Benin object classes, supports the proposal that

the corpus was created over a short period in his recent

article, “The Composition of Brass Objects from Benin,”

in Original—Copy—Fake? Examining the Authenticity of

Ancient Works of Art, Ernst Pernicka and Silke von Berswordt-

Wallrabe (eds.), Mainz: von Zabern, 2008): 145.