TILMAN HEBEISEN

119

cause Hebeisen had the ivory handles before he

manufactured the blades, he was able to manipulate

the iron so that it would protrude through

the handles’ bottoms (fi g. 7). This subtle detail is

present on many authentic African knife types,

lending credence to Hebeisen’s blades.

Though Hebeisen was a sound blacksmith, his

techniques were not African, as the analysis of

the Rider “Yakoma” revealed. But in case any

doubt remains that these blades were not manufactured

by the Yakoma, Hebeisen produced

several signifi cant photographs during his interviews

with Miersch. One depicts the Rider blade

(fi g. 10) and others depict two “Yakomas” that

Hebeisen would later discover on the market,

leading to his distressing revelation that he was

not in fact creating artistic reproductions but

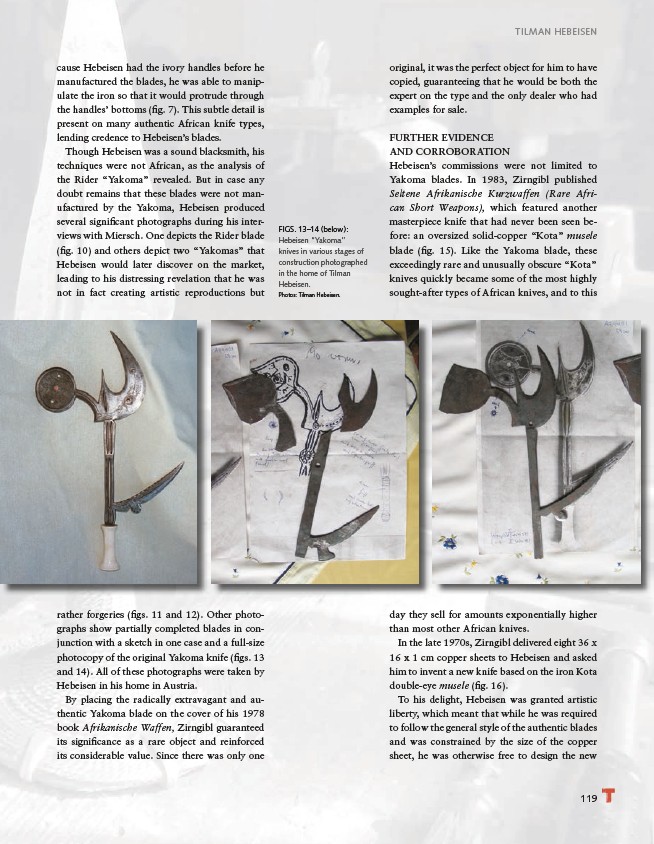

rather forgeries (fi gs. 11 and 12). Other photographs

show partially completed blades in conjunction

with a sketch in one case and a full-size

photocopy of the original Yakoma knife (fi gs. 13

and 14). All of these photographs were taken by

Hebeisen in his home in Austria.

By placing the radically extravagant and authentic

Yakoma blade on the cover of his 1978

book Afrikanische Waffen, Zirngibl guaranteed

its signifi cance as a rare object and reinforced

its considerable value. Since there was only one

original, it was the perfect object for him to have

copied, guaranteeing that he would be both the

expert on the type and the only dealer who had

examples for sale.

FURTHER EVIDENCE

AND CORROBORATION

Hebeisen’s commissions were not limited to

Yakoma blades. In 1983, Zirngibl published

Seltene Afrikanische Kurzwaffen (Rare African

Short Weapons), which featured another

masterpiece knife that had never been seen before:

an oversized solid-copper “Kota” musele

blade (fi g. 15). Like the Yakoma blade, these

exceedingly rare and unusually obscure “Kota”

knives quickly became some of the most highly

sought-after types of African knives, and to this

FIGS. 13–14 (below):

Hebeisen “Yakoma”

knives in various stages of

construction photographed

in the home of Tilman

Hebeisen.

Photos: Tilman Hebeisen.

day they sell for amounts exponentially higher

than most other African knives.

In the late 1970s, Zirngibl delivered eight 36 x

16 x 1 cm copper sheets to Hebeisen and asked

him to invent a new knife based on the iron Kota

double-eye musele (fi g. 16).

To his delight, Hebeisen was granted artistic

liberty, which meant that while he was required

to follow the general style of the authentic blades

and was constrained by the size of the copper

sheet, he was otherwise free to design the new