71

every time. I never cease to be amazed at how

foreign the autochthonous African religions are

to us, but I am equally surprised that no one

thinks of mentioning the Abrahamic religions

of Christianity, Judaism, or Islam, all of which

have been widely practiced in Africa ever since

they first existed.

T.A.M: How do you account for this?

B.W.: There are a number of reasons for it.

African religions were subject to scorn from the

time of the earliest contact with the West. As early

as 1455, the Romanus Pontifex papal bull issued

by Nicholas V authorized Portugal’s Alfonso V

and his successors to conquer Africa and to

convert and enslave its inhabitants. Because of

this, eradicating African religions was seen as a

mission of civilization. This view, which persisted

into the twentieth century, was perpetuated

throughout the colonial period, during which

missionaries promoted their faiths and presented

themselves as prepared for martyrdom—which in

fact is just another ecstatic act.

The paucity of knowledge about African

religions also has to do with the nature of its

practices, which are often localized and isolated.

Take ancestor veneration, for example. It goes

without saying that it doesn’t make sense for a

specific cult to exist across villages or communities

that don’t share common ancestors. Along the

same lines, when one reflects on the veneration

of nature spirits, one comes to realize that this

is often based on or associated with concrete

environmental elements—a forest, a river, a

mountain, etc.—that don’t move. However, when

these are individual entities, they frequently do

become syncretically integrated into different

beliefs systems, such as Benin Vodun or the orisha

cult of the Yoruba of Nigeria.

This vast and complex subject was clearly

worthy of an exhibition. Not only is there a

great deal to explain, but in my opinion it is

important to help our audience to understand

that taking an interest in African religions

requires enlarging the concept of exactly what

our Western societies normally considers a

religion to be.

T.A.M.: How did you structure the exhibition’s

discourse so that this is expressed?

B.W.: The common thread that runs through it

is the phenomenon of ecstasy, which is to say

the intense emotion that is aroused in a believer

when he or she becomes connected with a deity,

an ancestor, or a spirit. Since in the West the

religious experience has become a more intimate

question of a spiritual and philosophical nature,

it was important to me to show the diversity

of the spiritual states that religious practices in

Africa can give rise to.

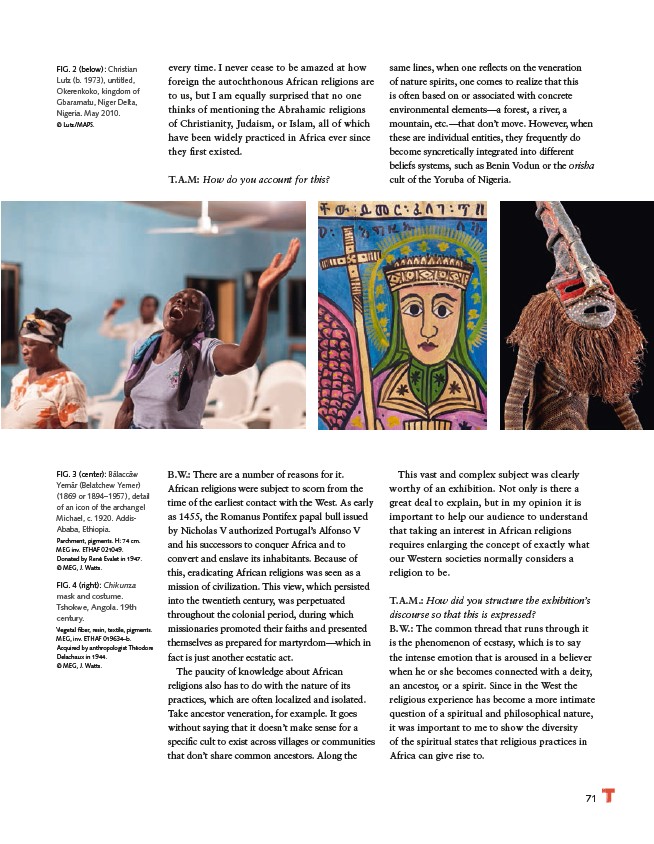

FIG. 2 (below): Christian

Lutz (b. 1973), untitled,

Okerenkoko, kingdom of

Gbaramatu, Niger Delta,

Nigeria. May 2010.

© Lutz/MAPS.

FIG. 3 (center): Bälaccäw

Yemär (Belatchew Yemer)

(1869 or 1894–1957), detail

of an icon of the archangel

Michael, c. 1920. Addis-

Ababa, Ethiopia.

Parchment, pigments. H: 74 cm.

MEG inv. ETHAF 021049.

Donated by René Évalet in 1947.

© MEG, J. Watts.

FIG. 4 (right): Chikunza

mask and costume.

Tshokwe, Angola. 19th

century.

Vegetal fiber, resin, textile, pigments.

MEG, inv. ETHAF 019634–b.

Acquired by anthropologist Théodore

Delachaux in 1944.

© MEG, J. Watts.