FEATURE

The Fantastic African Blades of

114

Tilman Hebeisen

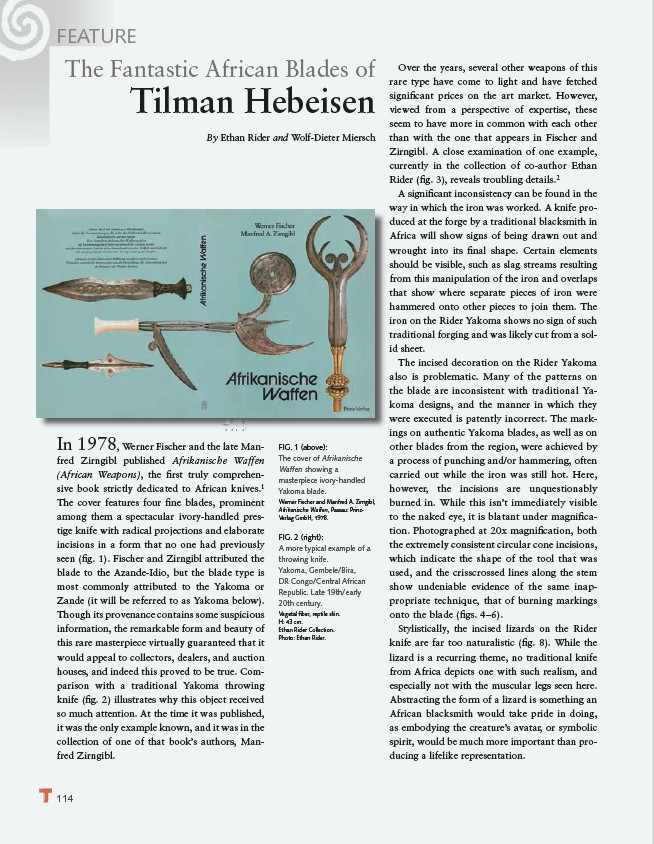

In 1978, Werner Fischer and the late Manfred

Zirngibl published Afrikanische Waffen

(African Weapons), the fi rst truly comprehensive

book strictly dedicated to African knives.1

The cover features four fi ne blades, prominent

among them a spectacular ivory-handled prestige

knife with radical projections and elaborate

incisions in a form that no one had previously

seen (fi g. 1). Fischer and Zirngibl attributed the

blade to the Azande-Idio, but the blade type is

most commonly attributed to the Yakoma or

Zande (it will be referred to as Yakoma below).

Though its provenance contains some suspicious

information, the remarkable form and beauty of

this rare masterpiece virtually guaranteed that it

would appeal to collectors, dealers, and auction

houses, and indeed this proved to be true. Comparison

with a traditional Yakoma throwing

knife (fi g. 2) illustrates why this object received

so much attention. At the time it was published,

it was the only example known, and it was in the

collection of one of that book’s authors, Manfred

Zirngibl.

Over the years, several other weapons of this

rare type have come to light and have fetched

signifi cant prices on the art market. However,

viewed from a perspective of expertise, these

seem to have more in common with each other

than with the one that appears in Fischer and

Zirngibl. A close examination of one example,

currently in the collection of co-author Ethan

Rider (fi g. 3), reveals troubling details.2

A signifi cant inconsistency can be found in the

way in which the iron was worked. A knife produced

at the forge by a traditional blacksmith in

Africa will show signs of being drawn out and

wrought into its fi nal shape. Certain elements

should be visible, such as slag streams resulting

from this manipulation of the iron and overlaps

that show where separate pieces of iron were

hammered onto other pieces to join them. The

iron on the Rider Yakoma shows no sign of such

traditional forging and was likely cut from a solid

sheet.

The incised decoration on the Rider Yakoma

also is problematic. Many of the patterns on

the blade are inconsistent with traditional Yakoma

designs, and the manner in which they

were executed is patently incorrect. The markings

on authentic Yakoma blades, as well as on

other blades from the region, were achieved by

a process of punching and/or hammering, often

carried out while the iron was still hot. Here,

however, the incisions are unquestionably

burned in. While this isn’t immediately visible

to the naked eye, it is blatant under magnifi cation.

Photographed at 20x magnifi cation, both

the extremely consistent circular cone incisions,

which indicate the shape of the tool that was

used, and the crisscrossed lines along the stem

show undeniable evidence of the same inappropriate

technique, that of burning markings

onto the blade (fi gs. 4–6).

Stylistically, the incised lizards on the Rider

knife are far too naturalistic (fi g. 8). While the

lizard is a recurring theme, no traditional knife

from Africa depicts one with such realism, and

especially not with the muscular legs seen here.

Abstracting the form of a lizard is something an

African blacksmith would take pride in doing,

as embodying the creature’s avatar, or symbolic

spirit, would be much more important than producing

a lifelike representation.

By Ethan Rider and Wolf-Dieter Miersch

FIG. 1 (above):

The cover of Afrikanische

Waffen showing a

masterpiece ivory-handled

Yakoma blade.

Werner Fischer and Manfred A. Zirngibl,

Afrikanische Waffen, Passau: Prinz-

Verlag GmbH, 1978.

FIG. 2 (right):

A more typical example of a

throwing knife.

Yakoma, Gembele/Bira,

DR Congo/Central African

Republic. Late 19th/early

20th century.

Vegetal fi ber, reptile skin.

H: 43 cm.

Ethan Rider Collection.

Photo: Ethan Rider.