TOM JOYCE

137

T. J.: I tend to respond to objects forged from

material with a previously known history and

symbolically shaped like another object, yet

forged too thin, too large, too heavy, or too

delicate to be used for any other purpose than

for a specific culturally relevant and agreed-upon

meaning. These attributes are often found

in currency forms or special-use trade tokens

in iron and copper alloy in the shape of blades,

hoes, ingots, bars, and tools. In addition to

these kinds of objects, I’ve also extensively collected

jewelry and body adornment such as anklets,

bracelets, neck torques, and amulets. I’m

also interested in musical instruments—lamellophones,

gongs, bells, flutes, and rattles—and

ritual implements including staffs, ceremonial

tools, figurative forgings, and devotional objects.

K. C.: You’ve been to Africa many times. Are

any of the objects you encountered during your

travels now in your collection, and what can

you tell us about them?

T. J.: Just one example is a clapperless bell called

ekpande from the Kabre region of north central

Togo that is played by male initiates during waa,

the fourth of five stages of initiation Kabre boys

undergo during their passage to adulthood.

The ceremony takes place every five years and

lasts ten days. The ekpande is the centerpiece of

an initiate’s outfit and is tied to his wrist with

a long, woven cord. It is swung in an arcing

gesture that lands the bell in the young man’s

palm, striking an iron ring worn on his thumb.

The instrument’s percussive rhythm is accompanied

by song, horns, whistles, and other bells

played by a procession of supportive family

members, neighbors, and friends.

K. C.: How did you come by it?

T. J.: In 2010, I was invited to attend the ceremony

by anthropologist Charlie Piot, a professor

at Duke University who was conducting

fieldwork in Kuwdé, Togo, where waa was

being held. Just before the event, I commissioned

Kao Kossi, a blacksmith in neighboring

Tcharé, where dozens of blacksmithing

families operate, to make his version of this

distinctive bivalve-like gong. After cold-chiseling

sections of a heavy recycled truck wheel

for starting stock, Kao and his assistant, Ide

Essozimna, forged two identical halves using

the powerful blows of a finely shaped stone

hammer atop an array of partially buried basalt

anvils. They drew out long, flat tabs at the

top and bottom axis of each concave half and

forge welded them to one another using clay

slurry as a flux.

Despite how “old school“ it may seem to

see blacksmiths working with stone tools and

pumping bellows on the ground, in the hands

of skilled practitioners who’ve grown up with

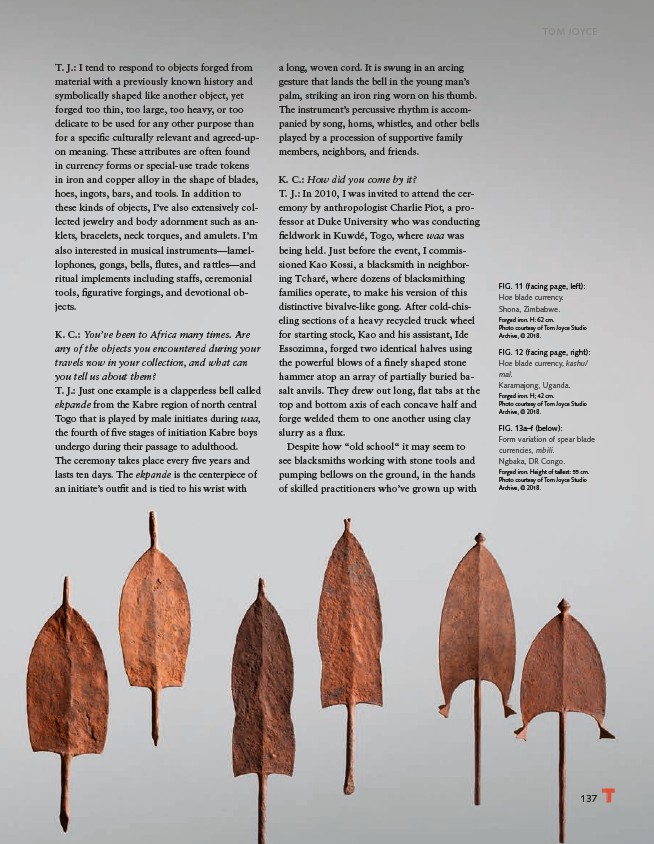

FIG. 11 (facing page, left):

Hoe blade currency.

Shona, Zimbabwe.

Forged iron. H: 62 cm.

Photo courtesy of Tom Joyce Studio

Archive, © 2018.

FIG. 12 (facing page, right):

Hoe blade currency, kashu/

mal.

Karamajong, Uganda.

Forged iron. H; 42 cm.

Photo courtesy of Tom Joyce Studio

Archive, © 2018.

FIG. 13a–f (below):

Form variation of spear blade

currencies, mbili.

Ngbaka, DR Congo.

Forged iron. Height of tallest: 55 cm.

Photo courtesy of Tom Joyce Studio

Archive, © 2018.