91

Facing page, clockwise from

upper left:

FIGS. 12 and 13: Masks.

Komo, DR Congo.

Wood, pigments, fiber.

H: 38 and 36 cm.

Private collection.

© CBAHRC.

FIG. 14: Mask.

Komo, DR Congo.

Wood, pigments. H: 31 cm.

Collected by Father Dassinoy.

Ex Pierre Dartevelle, Belgium.

Private collection.

Photo: Bernard De Keyser.

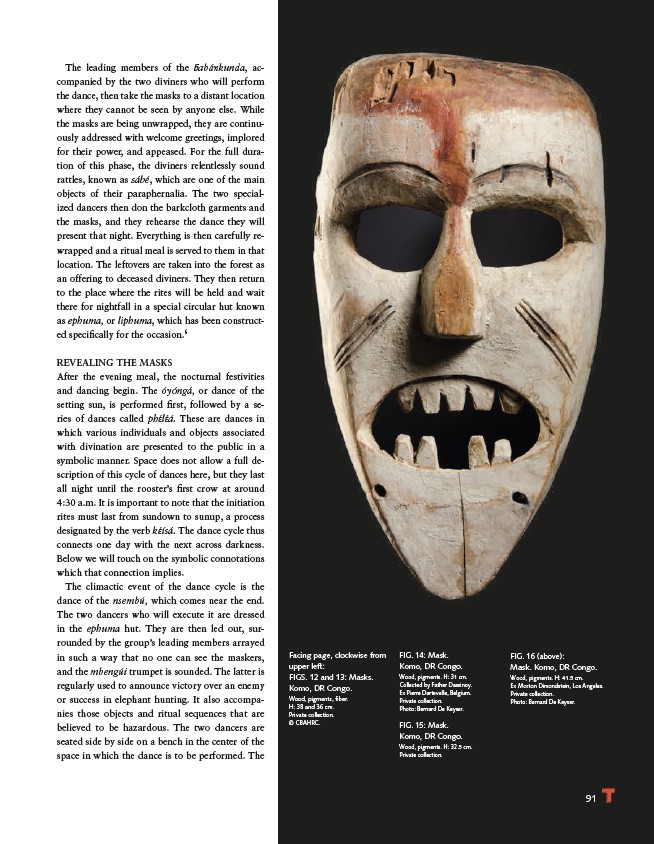

FIG. 15: Mask.

Komo, DR Congo.

Wood, pigments. H: 32.5 cm.

Private collection.

The leading members of the ƃabánkunda, accompanied

by the two diviners who will perform

the dance, then take the masks to a distant location

where they cannot be seen by anyone else. While

the masks are being unwrapped, they are continuously

addressed with welcome greetings, implored

for their power, and appeased. For the full duration

of this phase, the diviners relentlessly sound

rattles, known as sábé, which are one of the main

objects of their paraphernalia. The two specialized

dancers then don the barkcloth garments and

the masks, and they rehearse the dance they will

present that night. Everything is then carefully rewrapped

and a ritual meal is served to them in that

location. The leftovers are taken into the forest as

an offering to deceased diviners. They then return

to the place where the rites will be held and wait

there for nightfall in a special circular hut known

as ephuma, or liphuma, which has been constructed

specifically for the occasion.6

REVEALING THE MASKS

After the evening meal, the nocturnal festivities

and dancing begin. The óyóngá, or dance of the

setting sun, is performed first, followed by a series

of dances called phέlέá. These are dances in

which various individuals and objects associated

with divination are presented to the public in a

symbolic manner. Space does not allow a full description

of this cycle of dances here, but they last

all night until the rooster’s first crow at around

4:30 a.m. It is important to note that the initiation

rites must last from sundown to sunup, a process

designated by the verb kέísá. The dance cycle thus

connects one day with the next across darkness.

Below we will touch on the symbolic connotations

which that connection implies.

The climactic event of the dance cycle is the

dance of the nsembú, which comes near the end.

The two dancers who will execute it are dressed

in the ephuma hut. They are then led out, surrounded

by the group’s leading members arrayed

in such a way that no one can see the maskers,

and the mbengúi trumpet is sounded. The latter is

regularly used to announce victory over an enemy

or success in elephant hunting. It also accompanies

those objects and ritual sequences that are

believed to be hazardous. The two dancers are

seated side by side on a bench in the center of the

space in which the dance is to be performed. The

FIG. 16 (above):

Mask. Komo, DR Congo.

Wood, pigments. H: 41.5 cm.

Ex Morton Dimondstein, Los Angeles.

Private collection.

Photo: Bernard De Keyser.