bottom: an eagle, an orca, a grizzly bear, and a

sculpin (fi g. 12). The grizzly bear holds a human

fi gure upside down by its feet. An interesting detail

on the pole can be spotted only from afar: A

small human face peers out of the orca’s blowhole,

perhaps the subject of the eagle’s hungry

gaze. The totem pole was donated to the museums

in 1900 by Captain Gustave Niebaum, a

co-founder of the Alaska Commercial Company

and the former owner of Inglenook Winery in

Rutherford, California. It was fi rst installed in

the North American Indian Hall of the original

Memorial Museum building, placed, remarkably,

above a doorway between galleries.

In front of the totem pole sits another large

sculpture from the Northwest Coast: a bear

effi gy carved in the late nineteenth century by

a Haida artist (fi g. 13). The impressive work,

once in the personal collection of Andy Warhol,

was donated to the museums in 2013 by

Thomas Weisel. The bear is rendered at about

half scale and was likely part of a tall wooden

post. It would have represented the crest of

the artist, his patron, or his community.

18 Both this sculpture and the totem

pole were expertly carved from the

trunks of cedar trees. Not just any

cedar could have been used for such

robust sculptures. A specialist must

have searched the forests for a tree

81

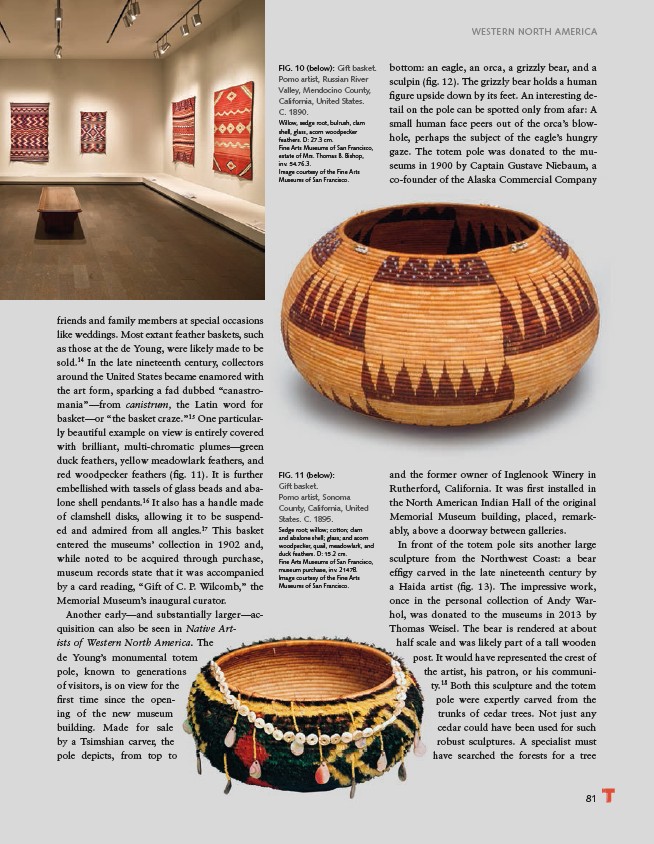

FIG. 10 (below): Gift basket.

Pomo artist, Russian River

Valley, Mendocino County,

California, United States.

C. 1890.

Willow, sedge root, bulrush, clam

shell, glass, acorn woodpecker

feathers. D: 27.3 cm.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco,

estate of Mrs. Thomas B. Bishop,

inv. 54.76.3.

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts

Museums of San Francisco.

FIG. 11 (below):

Gift basket.

Pomo artist, Sonoma

County, California, United

States. C. 1895.

Sedge root; willow; cotton; clam

and abalone shell; glass; and acorn

woodpecker, quail, meadowlark, and

duck feathers. D: 15.2 cm.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco,

museum purchase, inv. 21478.

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts

Museums of San Francisco.

WESTERN NORTH AMERICA

friends and family members at special occasions

like weddings. Most extant feather baskets, such

as those at the de Young, were likely made to be

sold.14 In the late nineteenth century, collectors

around the United States became enamored with

the art form, sparking a fad dubbed “canastromania”—

from canistrum, the Latin word for

basket—or “the basket craze.”15 One particularly

beautiful example on view is entirely covered

with brilliant, multi-chromatic plumes—green

duck feathers, yellow meadowlark feathers, and

red woodpecker feathers (fi g. 11). It is further

embellished with tassels of glass beads and abalone

shell pendants.16 It also has a handle made

of clamshell disks, allowing it to be suspended

and admired from all angles.17 This basket

entered the museums’ collection in 1902 and,

while noted to be acquired through purchase,

museum records state that it was accompanied

by a card reading, “Gift of C. P. Wilcomb,” the

Memorial Museum’s inaugural curator.

Another early—and substantially larger—acquisition

can also be seen in Native Artists

of Western North America. The

de Young’s monumental totem

pole, known to generations

of visitors, is on view for the

fi rst time since the opening

of the new museum

building. Made for sale

by a Tsimshian carver, the

pole depicts, from top to