FEATURE

each subsequent court was roughly the same,

including the oba’s audience hall.

This historical information makes it possible

110

to estimate the appearance of the audience

court. If approximately fi fty-eight pillars were

used in the display of the plaques, the size of the

corpus would equate to one pillar every three

meters with the possibility of greater openings

at the corner entrances and in the center of each

wall, where steps would have accommodated

those who were allowed to sit along the sides

of the gallery. There are approximately 820

plaques known to be in public and private collections

today and a number of plaques known

to be missing. In total, the known plaques would

cover a surface of 105 m2 (1,130 ft2). Using the

number of extant plaques and the approximate

number of pillars provided by von Nyendael, I

propose a rough calculation of sixteen plaques

per pillar, four on each side, so that each pillar

was fully encircled by the plaques.

Given the large space, it is unsurprising that

the brass casters would have designed an organizational

strategy to unify the corpus. The

direct casting method makes it impossible to

reuse the clay mold used to form each plaque,

and yet many authors have noted the existence

of “pairs,” or plaques with nearly identical

compositions. To date, these pairs have been

presented as interesting anomalies, but in reality,

the paired plaques form a regular part of the

corpus. Approximately 36 percent of all plaques

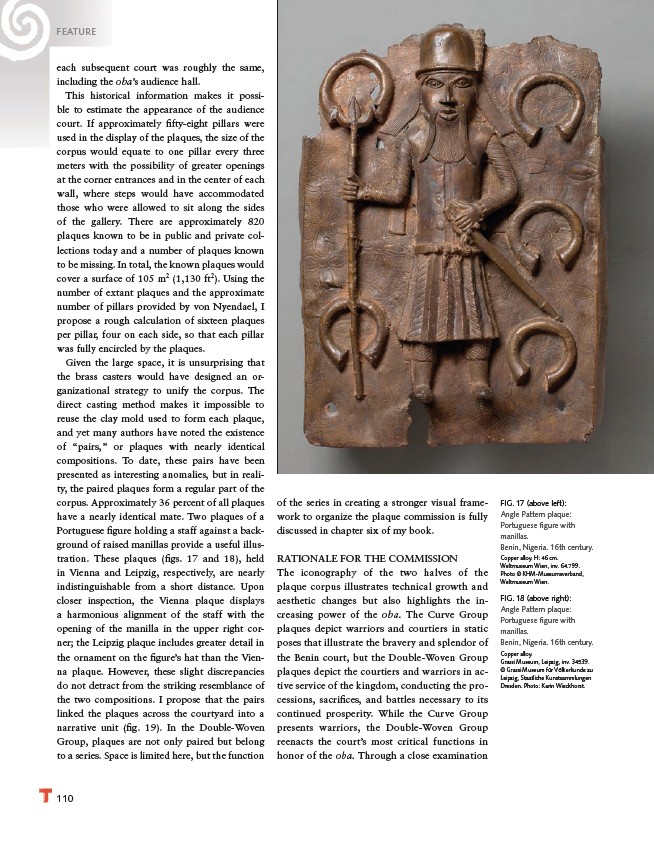

have a nearly identical mate. Two plaques of a

Portuguese fi gure holding a staff against a background

of raised manillas provide a useful illustration.

These plaques (fi gs. 17 and 18), held

in Vienna and Leipzig, respectively, are nearly

indistinguishable from a short distance. Upon

closer inspection, the Vienna plaque displays

a harmonious alignment of the staff with the

opening of the manilla in the upper right corner;

the Leipzig plaque includes greater detail in

the ornament on the fi gure’s hat than the Vienna

plaque. However, these slight discrepancies

do not detract from the striking resemblance of

the two compositions. I propose that the pairs

linked the plaques across the courtyard into a

narrative unit (fi g. 19). In the Double-Woven

Group, plaques are not only paired but belong

to a series. Space is limited here, but the function

of the series in creating a stronger visual framework

to organize the plaque commission is fully

discussed in chapter six of my book.

RATIONALE FOR THE COMMISSION

The iconography of the two halves of the

plaque corpus illustrates technical growth and

aesthetic changes but also highlights the increasing

power of the oba. The Curve Group

plaques depict warriors and courtiers in static

poses that illustrate the bravery and splendor of

the Benin court, but the Double-Woven Group

plaques depict the courtiers and warriors in active

service of the kingdom, conducting the processions,

sacrifi ces, and battles necessary to its

continued prosperity. While the Curve Group

presents warriors, the Double-Woven Group

reenacts the court’s most critical functions in

honor of the oba. Through a close examination

FIG. 17 (above left):

Angle Pattern plaque:

Portuguese fi gure with

manillas.

Benin, Nigeria. 16th century.

Copper alloy. H: 46 cm.

Weltmuseum Wien, inv. 64.799.

Photo © KHM-Museumsverband,

Weltmuseum Wien.

FIG. 18 (above right):

Angle Pattern plaque:

Portuguese fi gure with

manillas.

Benin, Nigeria. 16th century.

Copper alloy.

Grassi Museum, Leipzig, inv. 34539.

© Grassi Museum für Völkerkunde zu

Leipzig, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen

Dresden. Photo: Karin Wieckhorst.