objective of divination is to expose anything that

might constitute a threat to the social order.

Since everyone in Abálambú’s family considered

him to be a madman, he had no desire to teach

the divination process he had discovered to any

of his peers. Only Likóndó, his son-in-law and of

the Okaƃe clan, believed in his revelation, and he

was initiated into it by Abálambú. Likóndó became

86

Abálambú’s offi cial successor, and he in turn

recruited more disciples. Likóndó and his successors

further developed their form of divination

and ultimately founded an association, or brotherhood,

called the ƃabánkunda, and this caused earlier

forms of divination that had been individually

practiced to lose much of their prestige. Later on,

members of Abálambú’s Oƃúsé clan were also initiated.

During our stay in the area in the early 1970s,

Angɔní, a member of this clan who lived at kilometer

mark 76 of the Ituri Road, was considered to

be Abálambú’s legitimate successor, but the entire

organization of the group’s functions remained in

the hands of members of the Okaƃe clan and, more

specifi cally, with members of the Kεnεngɔa lineage.

Likóndó was a member of the Nsɔmƃei lineage,

but after his only grandson converted to Protestantism,

the leadership of the ƃabánkunda passed

to the Kεnεngɔa lineage, which was, at least in

part, rooted at kilometer mark 72 of the Ituri

Road. The other part of Kεnεngɔa lineage inhabited

Mpέnέluta, a village located 40 kilometers

north of Lubutu, where Musibule, a great-grandson

of Likóndó’s, still lived when we were there.

According to the elders who had known him in

their youth, Likóndó died sometime between 1910

and 1920. Thus Abálambú must have lived in the

second half of the preceding century.

Two important things can be deduced from these

facts. The fi rst is that the use of masks in Komo

culture is relatively recent, and the second is that

these masks were introduced from the northeast, a

more or less peripheral Komo area that lies at the

border between them and the neighboring

Lombi people.

WHAT THE MASKS REPRESENT

The pair of masks appears only at

important ritual events, most notably

when an initiate is officially confirmed

in his newly acquired functions

or when, in memory of a deceased diviner,

the cycle of rituals (ƃokúa) is

celebrated in his honor. It should be

noted that a commemoration of the

latter kind generally goes hand in

hand with a new initiation.

Not every diviner has nsembú masks.

They are the exclusive prerogative of

individuals who have direct affi liation

with one of the fi rst initiates and thus

play a leading role in the ƃabánkunda.

The masks, along with the barkcloth

garments (nsɔkɔ) that are worn by the

dancers, are moved from village to village for these

ceremonies. The diviner who owns them entrusts

them to a young man in his family who, on the

afternoon after he has been invested, must take

them to the village where the rites will be held and

where the group’s leaders will have already assembled.

The masks and the barkcloth garments are

carefully wrapped, since they must not be seen by

non-initiates outside the context of their ritual performance.

Generally speaking, the masks are called upon

to personify the spirit of divination, marking the

distance between that realm and any purely human

enterprise. They do not have a direct relationship

with the specifi c people or beings linked to their origins,

such as Abálambú, Likóndó, and the abúlá,

but rather serve as representations of all those who

FEATURE

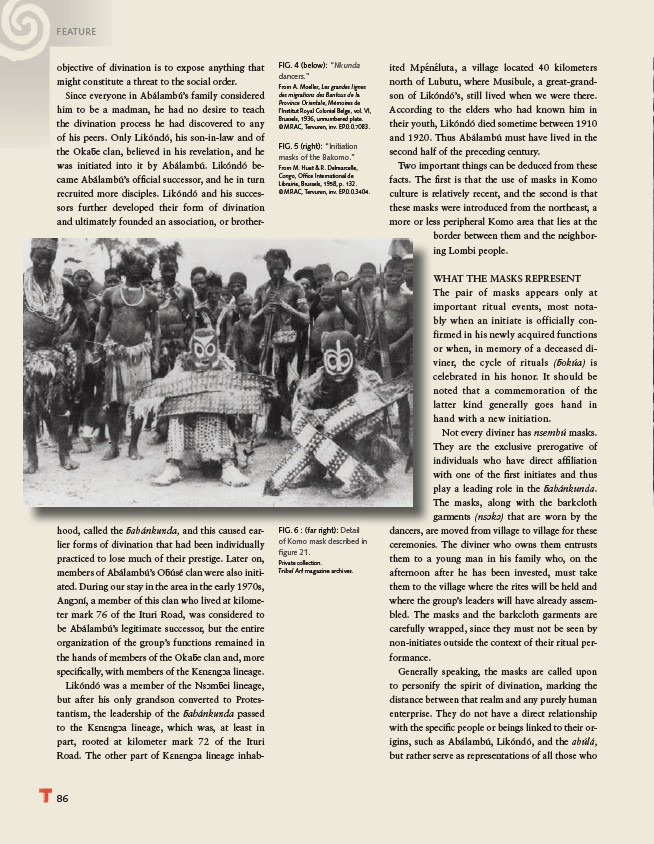

FIG. 4 (below): “Nkunda

dancers.”

From A. Moeller, Les grandes lignes

des migrations des Bantous de la

Province Orientale, Mémoires de

l’Institut Royal Colonial Belge, vol. VI,

Brussels, 1936, unnumbered plate.

© MRAC, Tervuren, inv. EP.0.0.7083.

FIG. 5 (right): “Initiation

masks of the Bakomo.”

From M. Huet & R. Delmarcelle,

Congo, Offi ce International de

Librairie, Brussels, 1958, p. 132.

© MRAC, Tervuren, inv. EP.0.0.3404.

FIG. 6 : (far right): Detail

of Komo mask described in

fi gure 21.

Private collection.

Tribal Art magazine archives.