FEATURE

120

ca, the comprehensive 2009 Taiwan exhibition.9

Hebeisen provided a photograph taken in 2003

of this very knife propped up on a rock in his

garden (fi g. 17).10

In keeping with his practice of creating false

histories for his knives, Zirngibl provided two

pieces of evidence to a private collector who

purchased one of the famous fi ve copper knives.

The fi rst piece of evidence is a picture of two

pages purportedly from the alleged L. A. Smith

book that relates the tale of Fullham and the

copper knives. However, in his 2017 article,

Barlovic determined this to be a composite of

invented material and snippets from an obscure

1913 book about a Ugandan journey.11 Barlovic

included a photo of this two-page spread in his

Kunst & Kontext article.12

Zirngibl’s second piece of evidence is a photograph

that is shrouded in mystery. The owner

of the photograph—actually a Polaroid of

an original photograph—will not allow it to be

seen, and a witness present on the day the photograph

was staged will not allow her name

to be revealed. However, both Miersch and

Barlovic have seen the photograph and relate

Toward the end of the 1960s, the author

fi rst heard about copper-bladed bird’s-head

knives. These knives, used by the Kota and their

northwestern neighbors the Fang, usually have

blades of steel. An excerpt out of a travel book

written by one L. A. (?) Smith mentions Sir George

Fullham, who was given fi ve of these copper

knives by a “Fan” chieftain named “Njong” as

tokens of appreciation for his successful treatment

of an eye infection. To quote from the book, “in

return, Njong had presented him with fi ve copper

knives, which, in form, all resemble vultures

or toucans. Later on he showed us these strange

knives, which were very heavy, some of them having

one, two, or three large, angular-shaped eyes.”

After “hunting” for these copper knives, for

years, which were originally in England and later

in the United States, the author fi nally succeeded

in obtaining all fi ve pieces.8

This tale resulted in the knives being widely

referred to in African weapons circles as the famous

fi ve copper knives of Sir George Fullham.

Zirngibl’s fl air for marketing led them to being

some of the most obscure, valuable, and sought

after of African knives. He sold one of them as

early as 1981.

After the publication of Seltene Afrikanische

Kurzwaffen, Zirngibl encountered a client who

wanted to purchase the copper blade published

in the book (Hebeisen’s fi rst “Kota”), but since

Zirngibl had decided to keep it, he commissioned

Hebeisen to manufacture a similar knife.

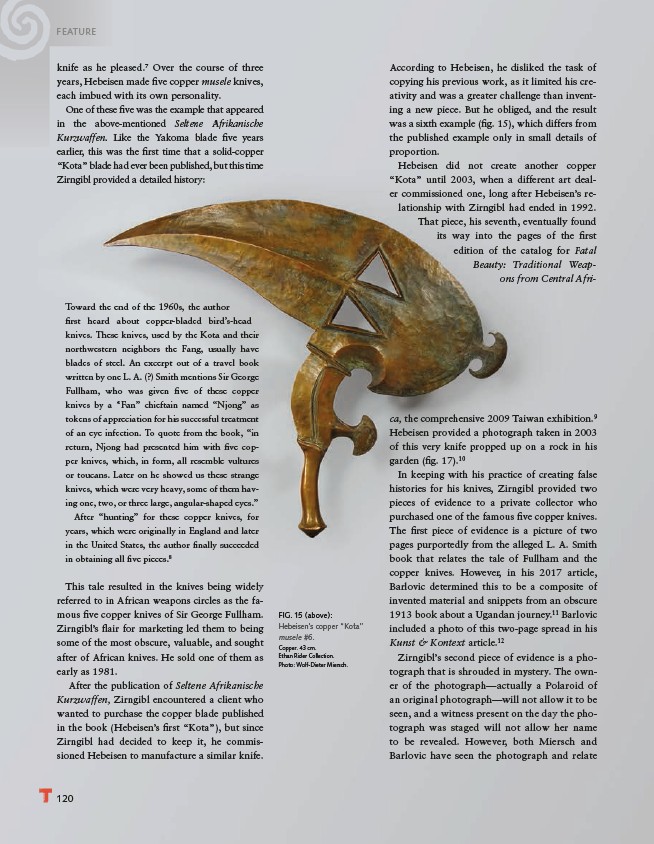

FIG. 15 (above):

Hebeisen’s copper “Kota”

musele #6.

Copper. 43 cm.

Ethan Rider Collection.

Photo: Wolf-Dieter Miersch.

According to Hebeisen, he disliked the task of

copying his previous work, as it limited his creativity

and was a greater challenge than inventing

a new piece. But he obliged, and the result

was a sixth example (fi g. 15), which differs from

the published example only in small details of

proportion.

Hebeisen did not create another copper

“Kota” until 2003, when a different art dealer

commissioned one, long after Hebeisen’s relationship

with Zirngibl had ended in 1992.

That piece, his seventh, eventually found

its way into the pages of the fi rst

edition of the catalog for Fatal

Beauty: Traditional Weapons

from Central Afriknife

as he pleased.7 Over the course of three

years, Hebeisen made fi ve copper musele knives,

each imbued with its own personality.

One of these fi ve was the example that appeared

in the above-mentioned Seltene Afrikanische

Kurzwaffen. Like the Yakoma blade fi ve years

earlier, this was the fi rst time that a solid-copper

“Kota” blade had ever been published, but this time

Zirngibl provided a detailed history: