PARIS 1931

97

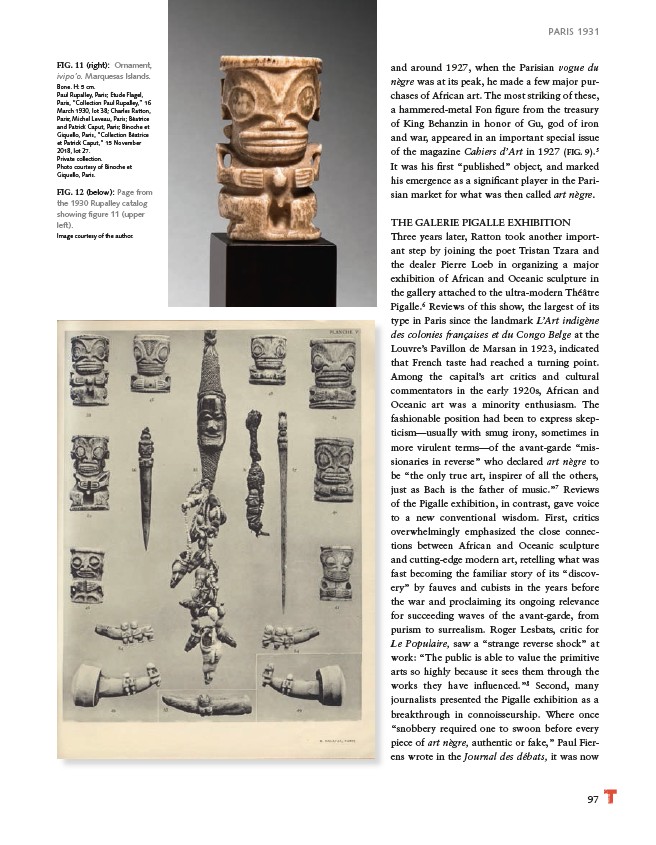

FIG. 11 (right): Ornament,

ivipo’o. Marquesas Islands.

Bone. H: 5 cm.

Paul Rupalley, Paris; Étude Flagel,

Paris, “Collection Paul Rupalley,” 16

March 1930, lot 38; Charles Ratton,

Paris; Michel Leveau, Paris; Béatrice

and Patrick Caput, Paris; Binoche et

Giquello, Paris, “Collection Béatrice

et Patrick Caput,“ 15 November

2018, lot 27.

Private collection.

Photo courtesy of Binoche et

Giquello, Paris.

FIG. 12 (below): Page from

the 1930 Rupalley catalog

showing fi gure 11 (upper

left).

Image courtesy of the author.

and around 1927, when the Parisian vogue du

nègre was at its peak, he made a few major purchases

of African art. The most striking of these,

a hammered-metal Fon fi gure from the treasury

of King Behanzin in honor of Gu, god of iron

and war, appeared in an important special issue

of the magazine Cahiers d’Art in 1927 (FIG. 9).5

It was his fi rst “published” object, and marked

his emergence as a signifi cant player in the Parisian

market for what was then called art nègre.

THE GALERIE PIGALLE EXHIBITION

Three years later, Ratton took another important

step by joining the poet Tristan Tzara and

the dealer Pierre Loeb in organizing a major

exhibition of African and Oceanic sculpture in

the gallery attached to the ultra-modern Théâtre

Pigalle.6 Reviews of this show, the largest of its

type in Paris since the landmark L’Art indigène

des colonies françaises et du Congo Belge at the

Louvre’s Pavillon de Marsan in 1923, indicated

that French taste had reached a turning point.

Among the capital’s art critics and cultural

commentators in the early 1920s, African and

Oceanic art was a minority enthusiasm. The

fashionable position had been to express skepticism—

usually with smug irony, sometimes in

more virulent terms—of the avant-garde “missionaries

in reverse” who declared art nègre to

be “the only true art, inspirer of all the others,

just as Bach is the father of music.”7 Reviews

of the Pigalle exhibition, in contrast, gave voice

to a new conventional wisdom. First, critics

overwhelmingly emphasized the close connections

between African and Oceanic sculpture

and cutting-edge modern art, retelling what was

fast becoming the familiar story of its “discovery”

by fauves and cubists in the years before

the war and proclaiming its ongoing relevance

for succeeding waves of the avant-garde, from

purism to surrealism. Roger Lesbats, critic for

Le Populaire, saw a “strange reverse shock” at

work: “The public is able to value the primitive

arts so highly because it sees them through the

works they have infl uenced.”8 Second, many

journalists presented the Pigalle exhibition as a

breakthrough in connoisseurship. Where once

“snobbery required one to swoon before every

piece of art nègre, authentic or fake,” Paul Fierens

wrote in the Journal des débats, it was now