PARIS 1931

113

many daily papers and small articles in a

few, had clearly done its work. The bustling

atmosphere, Gallotti wrote, was a striking

contrast with “the neighboring salerooms,

where antique furniture, Medieval tapestries,

and Louis XV clocks were being disbursed,

painfully, by brocanteurs whose

morale had been crushed by the rigors of

the economic crisis.” In the de Miré saleroom,

in contrast, “dumbstruck” spectators

heard “prices rising like skyscrapers with

the passage of each strange gris-gris and grimacing

idol.” These sums, in Gallotti’s view,

were entirely justified and proved that even

if “the general public” remained skeptical

of art primitif, “the number of those who have

discovered they can perceive its beauty, if they

choose to look at it attentively, is large enough

to refute the skeptics and to prevent them from

mocking the artists who have found such delight

in it.”37 The de Miré sale, in other words,

served as the commercial ratification of the aesthetic

conventional wisdom that had emerged

from the reviews of the Pigalle exhibition.

INNOVATIVE CATALOGS

Ratton and Carré’s innovations in these sales

did not stop at the use of carefully chosen

names. During the art nègre vogue of the later

1920s, cataloged sales that included African,

Oceanic, and Pre-Columbian objects had occurred

from time to time at the Hôtel Drouot.38

However, none of these auctions was treated

as a major event. Their catalogs were printed

in the typical Drouot format, as saddle-stitched

pamphlets with standardized typography and

covered in sheets of colored paper with pasted

labels giving the titles of the sales. The former

owners were generally anonymous or identified

by initials and the descriptions were cursory.

On the rare occasions when illustrations were

included, they were matter-of-fact photographs

tightly crammed onto a few pages. The catalogs

that Ratton and Carré produced for their

1931 sales broke sharply with this precedent.

Each one was perfect-bound and had a specially

designed cover. Though the object descriptions

were terse by present-day standards, they

were considerably more detailed than had been

the norm in previous ethnographic art sales.

Ratton and Carré also carefully phrased the

descriptions to indicate the relative importance

of particular lots. Some were simple enumerations

of salient formal characteristics, while

others offered a bit of ethnographic detail,

provenance information, and even flashes of

adjectival color. In the de Miré catalog, a seated

Dogon figure (lot 35, FIG. 54), was identified

FIG. 54 (far left):

Seated figure.

Dogon; Mali. Before 1931.

Wood, glass beads, fiber. H: 34.3 cm.

Georges de Miré, Paris; Etude Bellier,

Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 15 December

1931, lot 35; Charles Ratton, Paris;

Louis Carré, Paris; Jacob Epstein,

London (acquired after 1935); Carlo

Monzino, Lugano-Castagnola.

Laura and James Ross Collection,

New York.

FIG. 55 (middle left): Page

from the 1931 de Miré

catalog showing figure 54.

Image courtesy of the author.

FIG. 56 (near left): Page

from the 1931 Breton/

Éluard catalog showing

figure 57.

Image courtesy of the author.

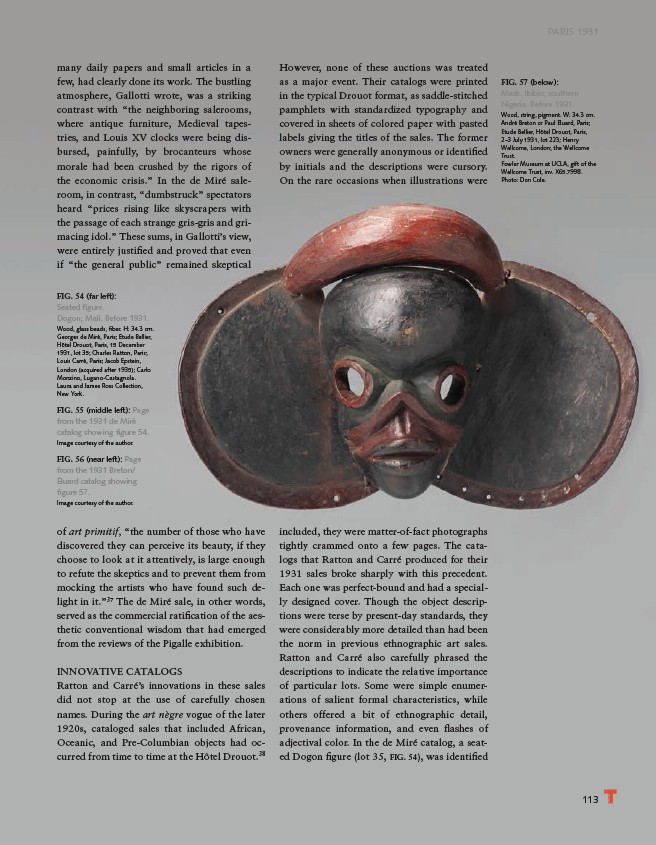

FIG. 57 (below):

Mask. Ibibio; southern

Nigeria. Before 1931.

Wood, string, pigment. W: 34.3 cm.

André Breton or Paul Éluard, Paris;

Étude Bellier, Hôtel Drouot, Paris,

2–3 July 1931, lot 223; Henry

Wellcome, London; the Wellcome

Trust.

Fowler Museum at UCLA, gift of the

Wellcome Trust, inv. X65.7998.

Photo: Don Cole.